A Taxonomy of Hurts

by Kate Dollarhyde

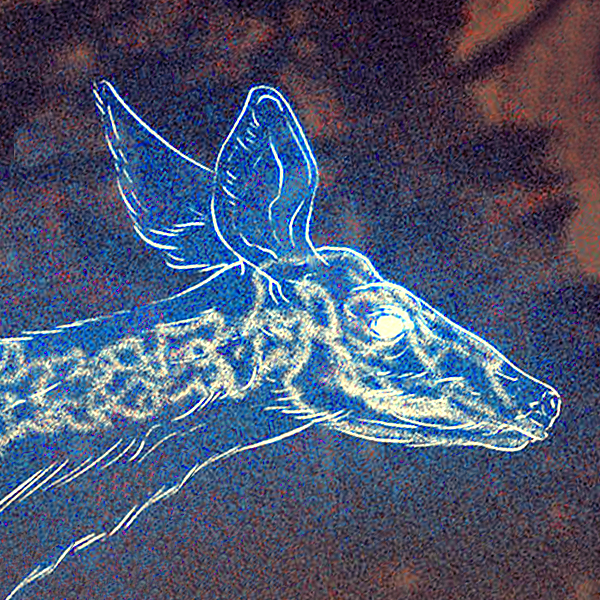

Illustrated by Kevin Tong | Edited by Julia Rios

August 2018

Penthos var. sturnus vulgaris

I’m in the outer avenues, the ocean-most edge of San Francisco, where the wind drags knives across the skin.

There is a man standing beside me at the bus stop, just he and I alone in the mist of morning. I look at my feet rather than him, but it’s really nothing personal; eyes are powerful, and the interlocking of them even more so, and it seems most men believe that when ours meet it is an invitation.

I hear a chittering screech and start. I look up. Starlings flock around the man in a cloud, twisting and convulsing. I look at him and he is staring past me, no doubt watching for the bus.

They are his most hurtful memories, and if I touch them, I can recall them as if they are my own. If I caught every starling, I could observe every awful hurt done to him.

One of the starlings darts by my face. I feel the brush of its wing against my cheek. I see the variegated speckles on its chest in exquisite detail. The next starling that comes by I snatch from the air. It fights the cage of my hands. I squeeze gently, and when my fingers feel the swift beating of its heart, I’m sucked through a sieve the size of the starling’s eye and arrive in another place.

I stand beside a young boy. I look out with him over a snaking river of cars twenty years too old. Is this time travel or a memory? Am I really with him in the past, or is the movie of his memory projected on my inner eye? Either seem improbable, and while I do believe in an infinite string of infinite universes wherein all things that can happen both have and will, I wonder yet again if I am losing my mind.

A group of boys beside him pull rocks from their pockets and throw them from the overpass we stand onto the freeway below. Brakes screech and metal grinds. The boy has a rock in his own hand, and when he refuses to throw it, the other boys throw their remaining rocks at him instead.

When the first rock strikes him, I am pulled back into my body at the bus stop. In my hands I still hold the starling, and the man beside me still looks on. I let the bird go and it joins the others, still screeching, still darting, still swarming a man at a bus stop on the edge of the world.

I am building a hypothesis, but it is yet unsatisfied. I grab another bird and I am back beside the boy with the rock, but he is much older. The red face of his father looms before us. I see blood on his mouth and a bruise blooming across his jaw.

Back in my body, I stumble into the street. The man grabs my arm.

“Watch it!” he shouts, and in his face I see his father’s.

Penthos var. phalaenoptilus nuttallii californicus?

Most people aren’t swarmed with memories. Every memory I capture is a hurtful one. Everything has the potential to cause pain.

No two people’s hurts take the same form; in the time since meeting the man flocked by starlings, I have seen others surrounded by constellations of lightning bugs, clots of jellyfish, or crusted in fractal coral growths.

I am preoccupied by a question to which there seems to be no answer.

Is the shape of our hurts determined by the types of pain we have suffered, by their severity? But that cannot be, for how can pain be classified? Some hurts are dull and aching, on fire with deep infection, while others are hot and sharp—yet the result, the pain, does not alone reveal what caused it.

The unexpected, messy death of a loved one will hurt you, but whether it is a sepsis that slowly rots you from your spongey marrow outward or burns briefly yet marks you indelibly like the stab of a tattoo needle is a formula that cannot be delineated, let alone calculated. The result is as individual as the hurt and everything that came before it. How does one classify a pain when one cannot classify a life?

I wonder if there are others like me, and if I have unknowingly met them, if they have held my hurts in the palm of their hands and remarked on how unremarkable, how small they are.

I wonder what form they take. Forgetful as I am, do I leave my hurts buried behind me like so many nightjars in torpor? Do they dig themselves into the dirt and wait for me to revisit them, like warmth revisits spring?

Penthos var. laccaria amethystina

I found Purvi three months after my encounter with the starling man.

We met on the subway when our train lost power in a tunnel. I saw the dull glow of her hurts in the dark and squeezed through the hushed crowd to find her. She smiled at me like she knew me. She made room for me beside her. She disarmed me with a question. And although I was suspicious, her hurts were like none I had ever seen, and I couldn’t look away.

A couple months later, Purvi and I share a small table at a restaurant I really can’t afford. Her hurts sprout from her skin in clumps of three and four. The old ones tend toward brown, but the new ones are amethyst-ine, brilliant and bright.

When she asks the waiter for our check, I reach for her hand. She entwines her fingers with mine, and with an awkward, furtive fumbling I thumb a hurt budding from her wrist.

Then I am standing beside her in an apartment I don’t recognize. The light through her kitchen window is the bright white of an early morning. She reaches for a ringing phone.

As she listens to the voice on the other end, her expression slowly falls, then freezes, a resigned grimace etched in the lines around her mouth. On her kitchen table is a letter—an offer of fellowship from a university in New York.

When she hangs up, I am back in my body, surreptitiously sliding around the private puzzle pieces of her life. I try to fill in the holes between the things I know.

I know that her mother has been asking the same questions over and over, calling at 6 a.m., lost, unable to find her way home. Her mother is elderly, and Purvi her only child; she has a responsibility to her she cannot abdicate. I know that Purvi was planning to move, and then suddenly she didn’t.

I know that she has had little time for me, and I had worried it was because of something I had done. And though now my unreasonable mind has found reason in her hurt, still I wonder if she knows what I am.

What am I? A raw nerve. A live wire. A bundle of hurts, same as she and anyone.

Penthos var. quercus agrifolia?

Pain cannot be classified, but the hurts that create it do take a definite form, and it is those hurts that can be categorized. I have named them for Penthos, the ancient Greek daimon of grief and lamentation, who visited again and again the same people, and at whose touch their breasts heaved and sobbed. Penthos, who drank deep from the well of others’ hurts and was never satisfied.

I see them everywhere, these walking wounded. I follow them and observe their actions, and from this I have drawn a new conclusion. The form our hurts take is dependent on who we are. They are distilled from the core of ourselves. It seems obvious in hindsight. Purvi’s hurts manifest as a mushroom, the amethyst deceiver. Deceivers are mycorrhizal—they live in symbiosis with the root system of their host plant. In mycorrhizal relationships, each half provides to the other what it cannot provide for itself.

I must know what form my hurts take. Do they hang from me as the bulbous acorns of Quercus agrifolia, fruits from which the bitterness must be leeched before they can be consumed? Or do they instead measure the span of my skin as the precise caterpillars of geometer moths do the length of oak leaves?

I fear what their form might say about me.

Penthos var. cosmia calami

It’s past midnight. Purvi holds my hand in the dark. The gills of her mushroom-shaped hurts breathe in the silence. They exhale dust and small pulses of green light.

She draws her fingers down my side and breathes against my neck. I feel her warmth against me, smell the sweat and salt of her unwashed hair, and know I should enjoy this human act of defeating loneliness, but—

I shrink away.

This was a mistake.

“What’s wrong?”

I don’t know how to have this conversation.

“Is it something I did?”

How do I begin to explain?

“Please talk to me.” Her voice is small, near a whisper. She buries her fingers in my hair, and I let her. That much I can stand. But I know it probably won’t be enough for her—not enough to last months, years, certainly not forever.

I stare into the shadows above my bed and wonder if my hurts are there, shrieking and swooping above me in the bodies of bats. Perhaps they are spiders and they build thick, ensnaring webs across my skin. Or maybe they’re moss and they grow in patches like bruises, covering my damp and crumbling log parts like a living bandage.

If Purvi could inhabit my hurts as I inhabit those of others, what would she see?

Me, in bed with someone else, and I would say, “I don’t want this. I’m sorry.” And he would say, “That’s okay. I love you.”

Me, in a bar, the weekend before my wedding. An old friend would joke, “…and even if you’re wasted, you have to fuck on your wedding night! Otherwise, what’s the point?” And she would see my partner squeeze my hand beneath the bar. But she would not see how in that moment I hate myself for not telling that friend off, for being this way, for hiding it.

Me, curled in a ball on the couch beside someone I loved. “We could have an open relationship. You could find someone else to do things I can’t,” I’d say. “No,” his response. “I only want you.”

My voice, reciting the constant thrum of dread that still beats beneath every thought: They will leave you. They will leave you. They will leave you.

Purvi sits up abruptly and snatches something from the air above us. She presents it to me with cupped hands.

“I want to do something for you.”

I stare at the cage of her hands. “What?” Wariness, distance—my best defenses.

“Will you just tell me what you see?”

The ghost of a grin haunts her face. She opens her hands, and in her palm is nothing.

I shake my head.

“Maybe not like that,” she mumbles, and I think she’s talking to me, but she’s turning her hand over slowly, as if something walks across her knuckles.

“Maybe…”

She presses her hand against mine. I begin to ask the obvious question, but she shushes me before I can get the words out. I pull my hand away, but she pulls it back.

“Hold still.”

She stares intently at the seam between our hands.

And then I feel a tickle in my palm. From off of her hand crawls a moth. It’s delicate and dun-colored and bumbles across my hand on six drunk little feet. Cosmia calami, the American Dun-bar. It takes to wing on midsummer nights and feasts on the young of other moths.

She exhales in a gust that almost sends the moth tumbling into the bedsheets. “Yes. I knew it.” Then, “You see it, right?”

“What is this?” I ask, and gesture vaguely, not knowing how to express what I want to know.

“Your memory, of course.” She takes the moth from my palm. The moment she does, it disappears. She settles in beside me.

“I’m not sure I understand,” I say.

“I thought when you approached me on the train… You saw mine, didn’t you?” She smiles. “You’re the first person I’ve met with moths. They’re beautiful.”

She doesn’t seem to want to talk about it, but she’s handed me a puzzle, and I can’t set it aside. “If I can see your hurts and you can see mine, then… can anyone with visible hurts see those of everyone else?”

She shrugs. “Sure, maybe, but you make it sound like there’re rules to it, and I’m not sure there are. It’s like, a way of seeing.”

Could the answer be that simple?

“I couldn’t quite figure you out, but then that one appeared just a minute ago, and it all sort of fell into place.”

In the silence between us, I hear the tick of the kitchen clock counting down the hour.

“I’m sorry that happened to you,” she says finally.

This was not within the parameters of my hypothesis, this possibility that Purvi would see the truth of me as I see her. But I can stretch and cut and stitch it to fit.

“Do you want to leave? It would be okay. I’d understand,” I say.

“Not unless you want me to. Are you trying to kick me out?”

“No! No. I just, you know.”

She reaches for my hand in the dark. If I hold still and focus on the press of her hand against mine, I can almost feel the tickle of my moth’s feet on my skin.

“What do mine look like?” She asks.

The eager edge to her question surprises a laugh out of me. As we wait for the sun to rise, I do my best to tell her.