Jul 24, 2017 | #Blackspecfic

The 2016 #BlackSpecFic Report

By Cecily Kane

The data that the #BlackSpecFic Report is based on is in this spreadsheet.

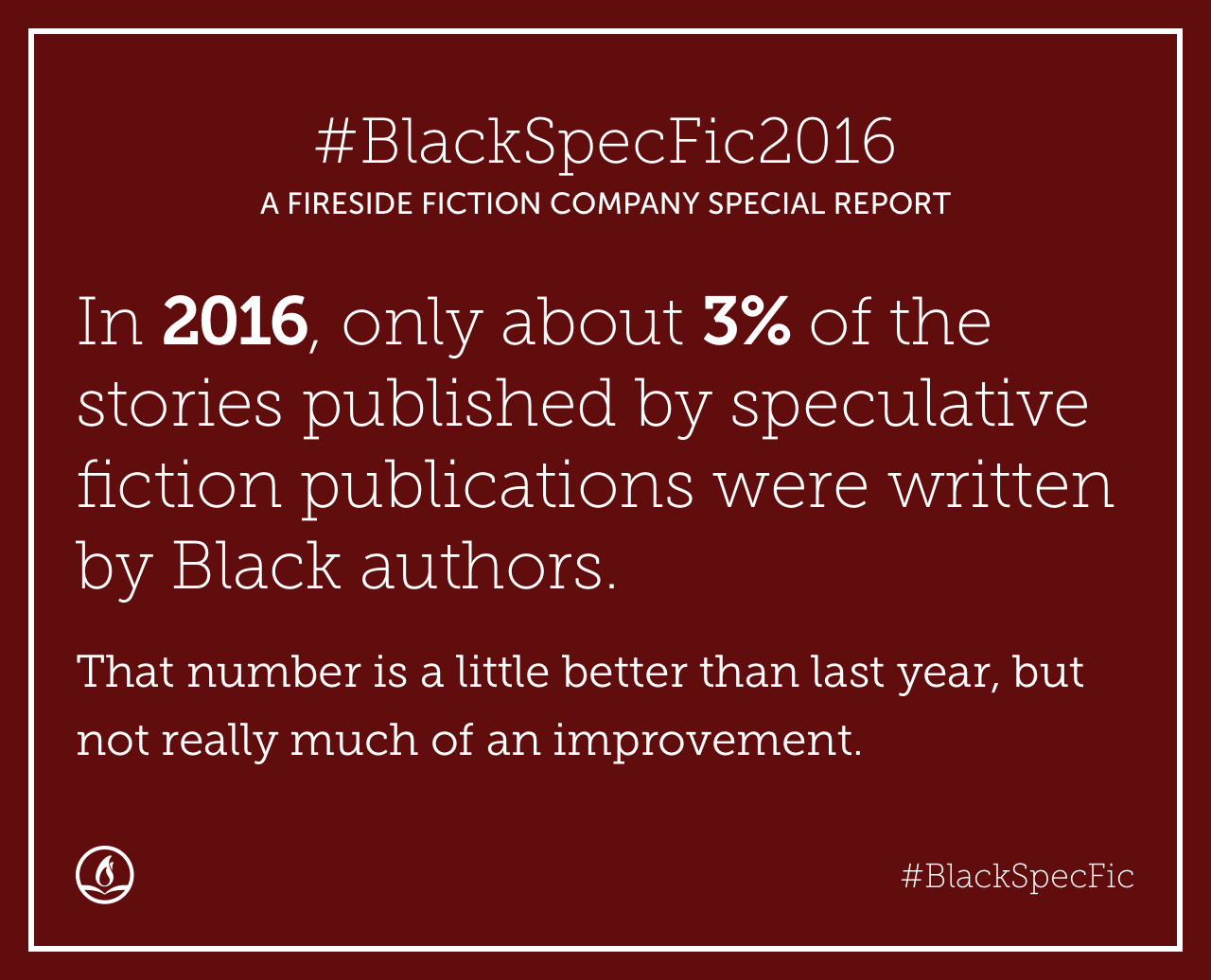

A couple of years ago, we1 noticed an alarming pattern in speculative fiction publications: while sometimes diverse in other ways, they published few to no stories by Black writers. Our 2015 investigation of over 60 science fiction and fantasy magazines confirmed those perceptions. Only about 2% of the original stories2 we could find in the field were Black-authored. Given that people of the African diaspora make up about 13% of the U.S. population and a larger portion of the world population 3, the discrepancy disturbed us. And the math suggested that there was no possible way this lack of representation was random happenstance.

A year after our initial report, many questions remain. To what extent is this problem due to submission and acceptance rates? And while it is almost assuredly both, how does the recursive4 nature between the two work? The sample and data points we have can’t fully answer those. There are questions for which numbers alone are inadequate to answer, and we think this is one of them. The data collected here seeks answers to other questions, the most important of which in our view is: within this structurally racist5 state of affairs, how are new writers faring? What happens when we take a deeper look at the field?

2015-2016

We limited this analysis to science fiction, fantasy, and horror magazines that pay professional rates as defined by SFWA, have been in existence for at least two years, and are open to general submissions. For both 2015 and 2016, we included additional data points: the number of unique writers, both Black and overall, and the number of stories by new Black authors.

We are considering the field both with and without the “People of Colo(u)r Destroy!” special issues of Lightspeed, Nightmare, and Fantasy Magazine, since they constitute a project that is limited to one year. Without these issues, a sample of 24 professional SF/F/H magazines yielded 31 stories by Black authors out of 1,089 total stories — that’s 2.8% — while 2.9% of 2016’s published unique authors are Black. In 2015 we found figures of 1.9% and 2.4%, respectively. While there’s no way to determine yet if these small increases are evidence of gradual long-term improvement or just normal variation — two years is too short a trajectory for that — perhaps we can find a cautious degree of optimism.

In our view, there’s a greater reason for hope.

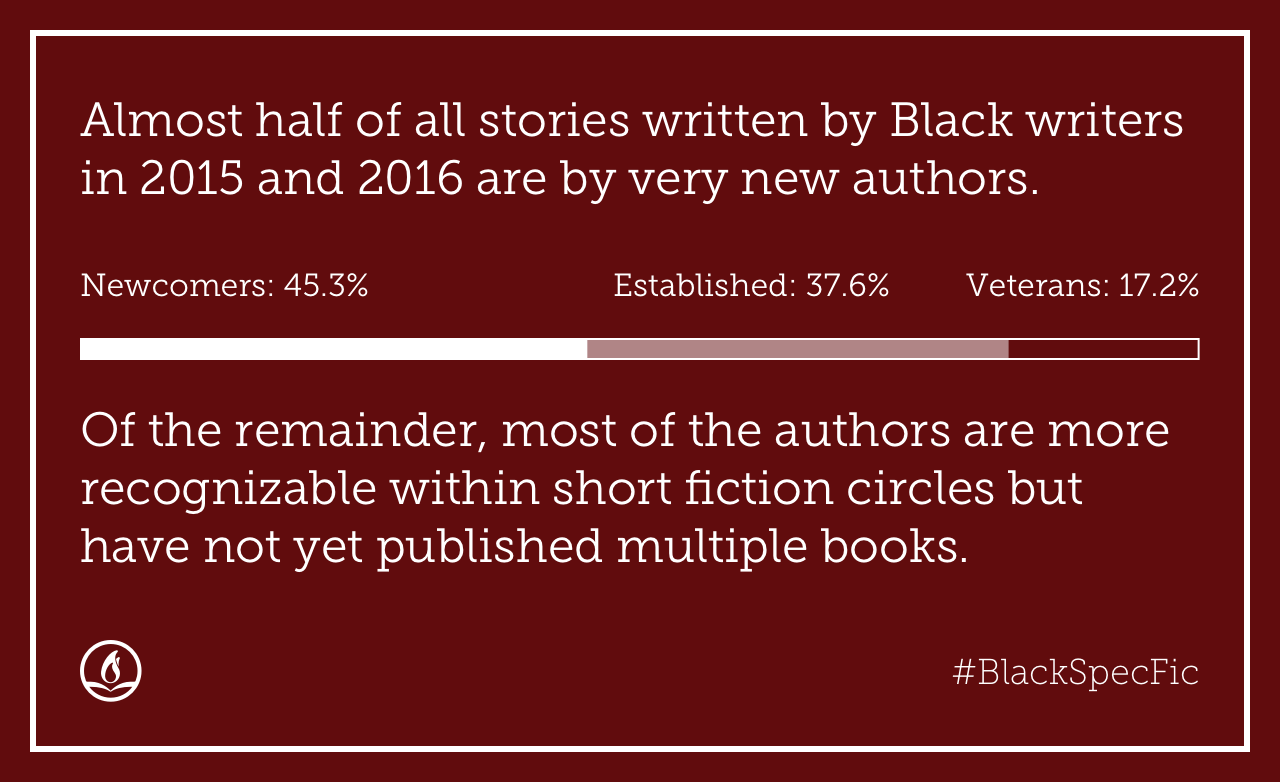

Almost half (45%) of the stories by Black writers we found in these two years are by very new authors6. Of the remainder, most of the authors are more recognizable within short fiction circles but have not yet published multiple books with large presses or won several literary awards. In the wake of the 2015 BlackSpecFic Report, many worried that the overwhelming majority of these few stories are by authors with household names; this is not the case. The 41 authors currently represented in the field possess a wide variation in experience and publication history.7

Effects of the “People of Colo(u)r Destroy!” Issues

In spite of comprising a tiny portion8 of the field’s story volume, the “PoC Destroy” issues collectively contained over 20% of 2016’s stories by Black authors. They alone raise the 2016 field-wide ratio by nearly a full percentage point, from 2.8% to 3.6%. Put another way: any improvements that took place from 2015 to 2016? The “PoC Destroy” issues are responsible for about half.

This is a major accomplishment of these issues’ editors. Speaking in a strictly quantitative sense, though, considering these issues’ scope9 and especially their size, a percentage increase of this magnitude should not have been possible, and would not be in a field that was healthy. This is not an argument for or against diversity-themed issues, a nuanced subject10, but rather a proportional look at what these illustrate about the whole: if such a small portion of the field can serve as a release valve for that much built-up pressure, the field is not functioning as it should.

As a further example, the “PoC Destroy” issues appear to have more than doubled Afro-Caribbean representation11.

Individual Magazines

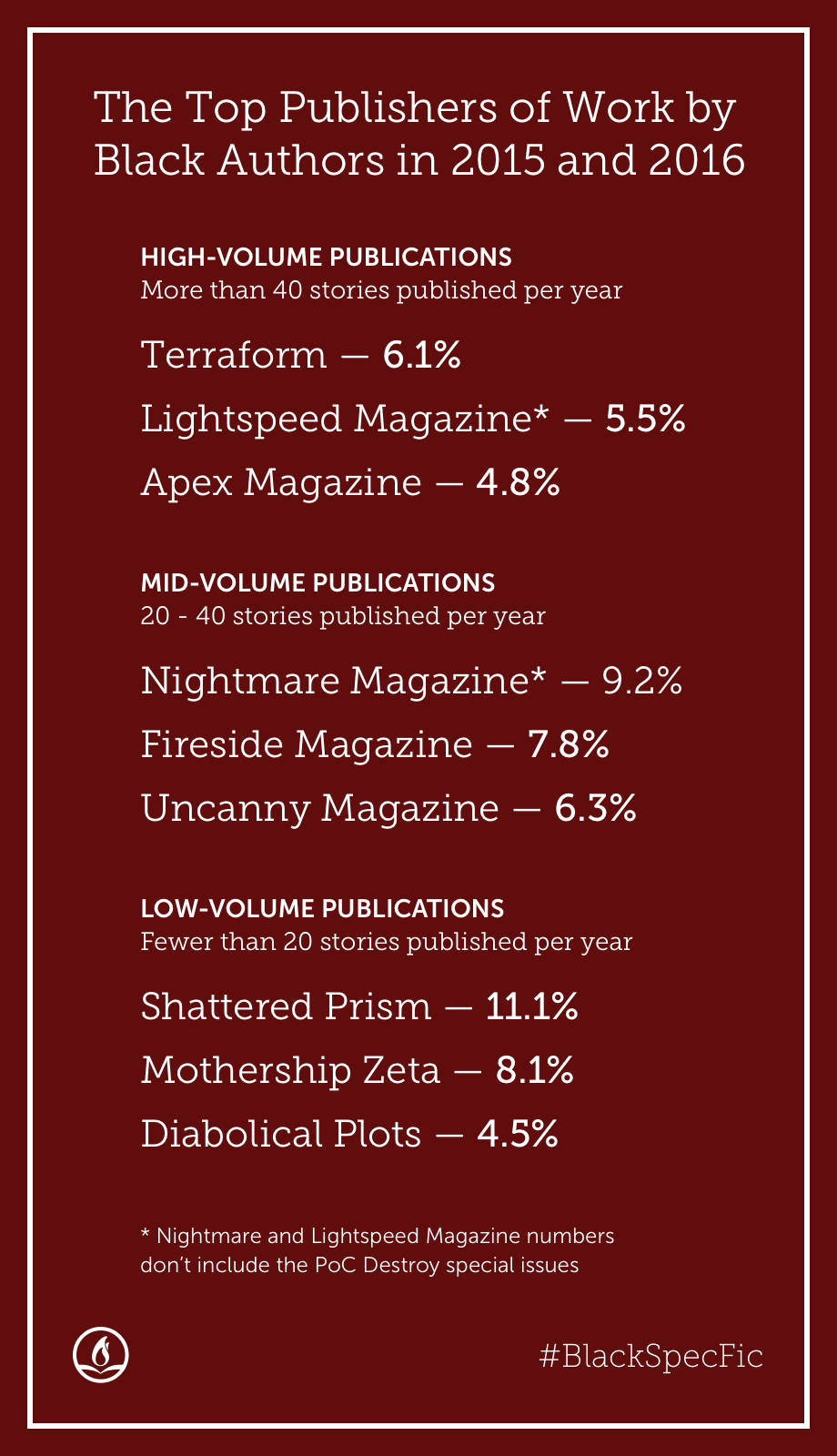

While these figures indicate an existential problem for the field as a whole, some magazines are performing better than others. The bulk of stories by Black authors published in 2015 and 2016 were in large part published in the exact same magazines.

The 9 professional magazines in this image12 constitute about 25% of the field’s story volume, and over the course of 2015-2016, they published:

- About 65% of stories by Black authors.

- About 80% of unique Black authors (as opposed to less than 40% in the 15 magazines not pictured).

- About 75% of stories by new Black authors.

In other words, according to every available metric, one-fourth of the field is publishing the vast majority of its Black work. There are disclaimers13 associated with the individual magazine data; however, the more information we collect, the more it points to a problem that can’t be explained by field-wide submission rates alone14. If it could be, why15 would the distribution be so uneven?

Furthermore, if the magazines that aren’t portrayed in this graphic caught up to the ones that are16, the number of stories by Black authors in the field would theoretically more than triple.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Again, we think there’s reason to have a degree of optimism. Some magazines made substantive changes to their editorial staffs and marketing strategies subsequent to the 2015 report, which was released late enough last year that any resulting improvements would impact only 2017 and beyond. It’s for this reason that this 2016 follow-up is not a comparative analysis but rather should serve as a baseline for comparison in future years.

Progress isn’t always linear; not all magazines have equal resources or lead times, which is why we want to hear from editors and publishers. What are your strategies for combating low publication rates of Black authors? Please answer our survey to let us know.

Black SF/F writers: we’d like to hear your comments and suggestions for how we can improve future reports. This also goes for data collection; we’re working purely from what’s publicly available on the Internet, and we don’t want to force people to publicly self-identify in order to be counted. If you suspect your stories are not included in this count and would like them to be, just want to double check, or have any other concerns — please let us know. Our email address is [email protected]; correspondence17 will be kept confidential.

White stakeholders in this field: remember that, while we live in a world that tries to convince us differently, “fault” and “responsibility” look similar but are fundamentally different paradigms.

This particular section of the report isn’t the source of many answers. For those, see both last year’s materials and upcoming ones: a roundtable with the staff of Fiyah Magazine and response essays by De Ana Jones, Chesya Burke, Maurice Broaddus, and Jennifer Marie Brissett, edited by Mikki Kendall.

-

1 — Author’s note: I use the first person plural throughout this article because many of its related decisions were derived via collective processes (though as their final arbiter, accountability for them rests on me).

How this article almost began:

“A major flaw of contemporary journalism is its feigned objectivity. This is largely accomplished by the removal of the writer as an actor; in most journalistic endeavors, the word ‘I’ never appears. And so, in writing up these findings, I found myself with two conflicting imperatives: my perspective is not very important (over the coming days, you’ll hear from some that are), and yet to remove myself entirely would reinforce the very problem this report seeks to redress: to play into that dynamic would be to pretend that a white person didn’t write this, would reify the mistaken conception held by whiteness that its perspective on racism is the most neutral and objective when it is in fact the least.”

I decided, insofar as such is possible, to remove myself from the article — these numbers don’t need me to narrate the story they tell — and confine my presence to the footnotes. However, given that 2015’s report received more scrutiny than nuclear power safety codes are subject to, and because identifying one’s positioning is important in these sorts of matters anyway, a clarification: I do not have official affiliations with any short fiction magazine in the field. (Nor have I ever submitted to any.) The only financial relationship I have is payment for this article. I do have many personal relationships in the field (indeed, I am friendly with several of its editors, most of whom do not come off well here), which is how this report ended up at Fireside rather than elseweb.

White writers who complain to me or Fireside about these numbers (rather than who they should be complaining to: their own editors) need to make these kinds of disclosures. ↩ -

2 — We aren’t counting reprints. Series and stories published in multiple parts count as one story. ↩

-

3 — See “The Black Population: 2010” Census Brief for U.S. population statistics. A single citable source for worldwide population statistics was not findable, but the population of Africa and its diaspora indicate that this proportion is higher. ↩

-

4 — “…[Black writers] don’t feel these markets are welcoming to their work; they find themselves often outside the networks that make submitting and publishing in these markets viable; and they don’t see stories published in these markets by people like them. So we seem to have wound ourselves up into an Ouroboros of a conundrum. SFF markets rarely publish black writers, hence less black writers submit to them, leading to less black SFF stories published by these markets.” Submitting SFF While Black by Phenderson Clark ↩

-

5 — Structural racism: “the normalization and legitimization of an array of dynamics — historical, cultural, institutional, and interpersonal — that routinely advantage whites while producing cumulative and chronic adverse outcomes for people of color.” From Chronic Disparity: Strong and Pervasive Evidence of Racial Inequalities by Keith Lawrence and Terry Keleher. Further: “Structural racism is not something that a few people or institutions choose to practice. Instead it has been a feature of the… systems in which we all exist.” From the Aspen Institute.

In other words, this isn’t about whether individual editors sport white robes and hoods on the weekends; nobody actually thinks that they do. Active bigotry is not strictly necessary for the building and maintenance of systems that benefit white people to the detriment of people of color. Undoubtedly, a combination of factors contribute to this problem; while identifying to what extent each plays a role is very useful for practical purposes, none are rebuttals to the fact that available evidence, quantitative and qualitative, points to a racist outcome. There’s a faction of people for whom Moses descending the mountaintop bearing tablets inscribed with “TOTES RACIST, DUDES” would be inadequate evidence; they are not our intended audience. ↩ -

6 — We are defining “new author” as currently eligible for the Campbell Award or not yet eligible (at the time of the story’s publication). “Veterans” are authors who have 3 SF/F/H books published with big 5 presses and/or 3 SF/F/H literary award wins (solo or in combination). “Established” authors are those who are no longer eligible for the Campbell, but for whom the latter criterion does not apply. ↩

-

7 — In order to see how the field is treating new authors, we had to use discrete categories with objective markers; this approach is somewhat flattening. Even within these groups, there’s wide variation; “new authors,” for example, are mostly recent debuts, but this category also includes an award-winner in multiple genres outside of SF/F/H and a film director, as well as a few authors who have published acclaimed novels with small presses or presses outside the U.S./U.K. (There’s also similar arbitrariness to the “established” categorization.) We wanted to make explicit the fact that this classification system is inherently reductive (as well as based on parameters that are ultimately American-derived), even as it indicates a sign of health outside the appalling lack of representation overall.

Future reports, however, may use a different set of parameters for these determinations. ↩ -

8 — Altogether, the PoC Destroy issues contained 28 of 2016’s 1,117 stories; about 2.5% of the total story volume. ↩

-

9 — These issues were dedicated to publishing people of color generally. About one-third of the stories within the combined issues were written by Black authors. ↩

-

10 — Any one quote rendered in isolation would be overly reductive; see for example The Fireside Fiction Report: A Reader/Critic’s Perspective by Leslie Light for a discussion of this matter. ↩

-

11 — We also took a look at the diaspora. We aren’t reporting numbers on this for various reasons (not the least of which is that we don’t want to incentivize publishing one part of the diaspora “over” another); we didn’t find anything particularly unexpected. Let this serve as a reminder, though, that within a group that’s dramatically underrepresented, there are subsets who are virtually unrepresented. We know that Caribbean SF/F writers exist, today and twenty years ago. The Afro-Caribbean population is about the size of Canada’s population; that’s a very large set of perspectives to be almost wholly missing, and the field cannot help but suffer from that lack (as well as others). ↩

-

12 — For clarity’s sake, this graphic portrays percentage of stories by Black authors published. Were we to use percentage of Black unique authors as the metric instead, some portrayed figures would change slightly — up to +/- 1.5%. Specifically, Uncanny and Fireside would switch places, as would Apex and Lightspeed. ↩

-

13 — As with 2015’s report, per-magazine data is less reliable than the overall data set; a false negative would alter an individual magazine’s percentage to a greater extent than the field-wide percentage, where any change would be fractional. Quantifying uncertainty in this case is more complex than an “unknown rate” and is a work in progress; for now, we’ve highlighted the handful of magazines in the spreadsheet for which we’ve estimated uncertainty to be greater than average. This is less for quantitative purposes than for the sake of not potentially unduly discouraging submissions. ↩

-

14 — The data from Fiyah Magazine’s BSF report can’t be directly applied to this one, as its sample is different both in population and in timeframe, but we can be fairly confident thanks to its findings that submissions are highly variable across individual magazines. Perhaps the editors of magazines with actual or suspected very low submission rates ought ask themselves why that might be the case. ↩

-

15 — This question is rhetorical ↩

-

16 — Staff of magazines that are performing adequately-to-slightly-better-than-abysmally, including Fireside, should not take this as an invitation to rest on their laurels. ↩

-

17 — Legitimate. Legitimate correspondence will be kept confidential. White tears and proffered cups from the Well of Actually may not be.

(h/t to Alexandra Erin for this phrasing) ↩

About the author

Help us keep this conversation going

We spend around $1,700 paying the various people involved in producing the #BlackSpecFic report and its accompanying essays every year. This type of work is a core part of our mission, and it is only possible due to your direct support.

You can make a one-time contribution directly to our #BlackSpecFic fund, or back us more broadly by becoming a Fireside subscriber. Either way, your cash will go toward helping us ensure a bright future for a thriving, sustainable, and inclusive field.