By the Mother’s Trunk

by Lisa M. Bradley

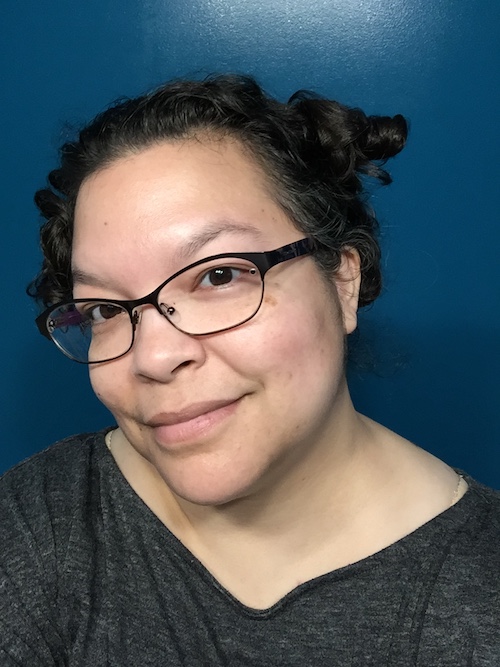

Edited by Julia Rios

March 2018

Elephants have 1,948 olfactory receptors. Dogs have 811. Humans have only 396, fewer than guinea pigs or softshell turtles. An elephant can smell water 12 miles away.

Tillie considers the Mississippi—so thick and ever-flowing it must issue from the Mother’s Trunk itself—to be her faithful travelling companion. For weeks its lotus-studded banks have rarely strayed a mile from where Tillie rides the rails, visiting town after town of squealing children.

The river’s slippery, splashing scent-shapes spread like duckweed across her olfactory landscape, melding with the straw and dung in Tillie’s car, the ponies, oats, and saddles next door, and on the other side, Old Lion’s tooth decay, acrid as the train engine’s breath.

When the circus disembarks in St. Louis, Tillie parades with the others to their temporary camp, a courtyard called Four Corners. There, the Mississippi’s omnipresent musk is swiftly overpowered by the stench emanating from the tall, brick buildings. One serves as a pen for soiled, captive humans; the other, a barrow for the recent dead. Staked between prison and morgue, Tillie tries to focus on the dandelions at her feet, sparse but refreshingly green against the roof of her mouth. Tremors funnel up her feet, assuring her the trains are still running, will soon carry her far from here.

At night her dim eyes detect sporadic green twinkles flitting through the air. Beyond her trunk’s reach, they remind her of sun sparkles through the slats of her train car, but they flash slower, softer. She imagines she is back in her box and rocks herself to sleep.

An elephant’s skin is almost double the size of the elephant. A female Indian elephant’s skin may measure up to 69.5 feet squared. Though an elephant’s skin has several nerve centers, it is, at most, 1.2 inches thick and easily sunburned. Elephants lack sweat glands.

Tillie lowers her shaggy lashes against insistent summer light. In the blood-tinted darkness behind her lids, she perceives differential, overlapping bands: not of color, but of density, the degrees of moist heat radiating from sky and glass and stone.

She received a bath earlier this morning, but the water droplets that caught in the coarse hairs on her head have already evaporated. She would like to dust herself but Governor says, “It’s SHOWTIME.” Tillie trusts the water trapped in her wrinkles will keep her cool until break time. Governor gives lots of breaks. He is the most generous master she has known. She is eager to please him, happy to perform. She is also more than ready to escape the miserable scents of prison and morgue.

Tillie opens her eyes. Men with funny hats and piercing whistles hold back horse-drawn carts and carriages, allowing the circus procession to file onto the cobblestone street. Tillie marches alongside Governor at the front. She lifts her trunk and smiles. She is “Giving the PEOPLE what they WANT,” as Governor says.

Even with her poor eyes, Tillie sees that humans line the street. What elaborate costumes the audience wears! Some sport bonnets tied to their heads with colorful ribbons that stick to heat-splotched cheeks. Many totter on their toes, like the dancing poodles farther back in the procession. Others have top hats like Governor wears with his red-and-black ringmaster’s finery, but they hold their hats instead of wearing them. They must be as hot as Tillie is, for some have removed their coats. Collars wilt and neckties droop. Still, how nice of everyone to dress up for the circus.

Meanwhile, children scamper up metal trees to see over the adults’ heads. When Old Lion snarls at the fleas biting his ears, the children squeal, thrilled.

Tillie wades into the city smells. Cat piss. Horse-hair and wool bundles swathed in fabric and balanced on the tip-toeing people’s rumps. Very curious. Straw bundles filling other people’s rump ruffles. Flower juice mingled with human sweat. Horse dung. Sludge from emptied spittoons and chamber pots. Rotting garbage. And something new: damp newsprint, not wet in the gutters but in human hands, wrapped around cold, hard water that the people nibble at. Tillie would like to taste that.

The procession arrives at a brick ridge where even more people await, swarming like ants. This is not the BIG TOP. How can they “give the PEOPLE what they WANT” here?

The Mississippi’s alluvial smell reemerges but is complicated by coal haze. The caustic breath of steamboats and locomotives burns the inside of Tillie’s nose. She clenches her nostrils shut but can do nothing about the sun cooking her skin.

Tillie, an Asian elephant born in the wild, was acquired by the John Robinson Circus in 1872. According to circus lore, she was 120 years old at the time of her death. Historians estimate her age as closer to 65 years.

Tillie has often been told she is a Good Elephant. She is not sure the Mother creates Bad Elephants. Even Tillie’s surliest brethren have their reasons for refusing commands.

Tillie considers herself a WELL-BEHAVED elephant. She quickly learns routines. She trumpets on command. During performances, she ignores distractions like crying children or squabbles among the dancing poodles. Often, the trainers don’t even tie her to a stake between shows, a point of pride for her: they trust her not to trample anything or attempt escape. Certainly they haven’t needed to use a bullhook on her for years. Not since she was a new, nervous addition to the circus.

So Tillie is wary when the Strongman approaches her with a hooked metal guide in one beefy fist. She looks to Governor for guidance, but he is signaling to three roustabouts also equipped with hooks. The men surround her. Not looking at Tillie, Governor reaches back for her trunk, which she promptly wraps around his hand. He begins walking toward the crowd assembled on the ridge and she follows, quickly, before the men have any excuse to prod her with the hooks.

Tillie is accustomed to the shouts of barkers on the midway, so she pays no mind to the men declaiming on the ridge. She is too focused on her own strange circumstances.

Still clasping Tillie’s trunk, Governor snaps the fingers of his other hand. An aerialist in spangled gear scurries forward to swap the ringmaster’s baton for a burlap sack. The aerialist then slinks away, and Tillie realizes the rest of the procession is not following. They are staying behind, as if suspicious of the ridge.

The tongue-tingling aroma of tart apples coming from the burlap sack does not please Tillie as it usually does. The sun has sapped the last droplets from her skin. The tips of her ears feel incandescently hot. She flaps them once, twice for relief. She’d like to lower the curtain of her shaggy eyelashes against the blistering sun. Instead, she follows Governor, waiting for a cue.

The world’s first all-steel bridge was the James B. Eads Bridge, constructed over seven years in the post-Civil War depression. Linking St. Louis, Missouri, and East St. Louis, Illinois, over the Mississippi River, the Eads Bridge is approximately 322 Asian elephants long. Its clearance over the river is 88 feet, about 11 elephants.

Once the declaiming peters out, Governor finger-signs into Tillie’s curled trunk, and Tillie knows to lower her mouth to his ear. A moment later, into the crowd’s waiting silence, he announces, “Tillie wants me to tell you she does this for God and Country—and HOT ROASTED PEANUTS!”

Slightly reassured by laughter and cheers—they must be giving the PEOPLE what they WANT—Tillie follows Governor onto what looks like a long, abandoned road.

Unfortunately, the retinue of men with hooks comes, too, their sweat reeking of fear. Tillie’s heart speeds up. Frightened men are often brutal men, even when they’re not wielding hooks.

Behind them, the crowd buzzes, same as when Governor promises a TRULY GRAND FEAT. Usually that means the aerialists will do something without a net, or the lion tamer will taunt Old Lion into a burst of senile ferocity.

Tillie is unsure how this leisurely amble can be a GRAND FEAT. As they walk up a very slight incline, Governor releases her trunk and gives her an apple from his bag. She curls her finger around the fruit but does not lift it to her mouth. Even with Governor’s murmurs of encouragement, she is too nervous to eat. She notes tension tightening his usually bold stride. She senses the bullhooks mere inches from her skin.

Eventually, her ridged, cratered heels detect a change in seismic waves. It distracts her from the sunburn spreading over her thin-skinned ears, less so from the hooks waiting to jab her. She senses the brick “road” beneath her feet does not connect to the ground. The layers of stone and metal only go so far before opening up into a cavern below. But, under that, rather than a cavern floor, the ricocheting seismic waves suggest there is liquid. Tillie’s feet and brain ratchet details back and forth like beads on an abacus: the road’s depth, density, her weight…

The Mississippi River smells farther away, but its fertile aroma wafts up to her, cutting through the roustabouts’ fear. By the Mother’s Trunk! Tillie is going over the river. She can’t swivel her head to investigate, not in the middle of a performance, but she trusts her nose.

At the highest point over the river, Governor leads Tillie in a small circle. Mid-turn, her heartbeat clogs her ears, deafening. Dizzy, so dizzy. She remembers a skill developed early in her circus career and concentrates on not crushing the apple in her grip. Memory primed, she recalls something even deeper in her past. As a baby, she rode in a basket, big enough for her and many men, across the Mother’s Bath. Her stomach had roiled, as it does now, but she made it to the other side.

Her heartbeat leaves her ears and she hears, from a great distance, cheers and whistles. Tillie does not know that the railroad tracks on both sides of the Mississippi have been cleared, the arches of the Eads Bridge evacuated. She cannot make out the crowds of stevedores and dockworkers marking her progress from the shores. She smells the steamboats anchored up- and downriver but not the passengers and crew who have packed the boats’ decks, shielding their eyes to marvel at her.

Bowing and flourishing his top hat, Governor milks wave after wave of applause from the audience. Eventually, he escorts Tillie down the other side of the long road. At the end, another massive crowd awaits. There is more declaiming by men she cannot find in the knot of people, but their words aren’t audible over the people’s cheers and the horn blasts from trains and steamboats.

Tension drained, Governor yells about God and HOT ROASTED PEANUTS again. The Strongman and roustabouts bark with relief masked as laughter. They and their bullhooks disappear into the crowd. If muscles can sigh with relief, Tillie’s do.

Then Governor tugs her ear, and Tillie bends her elbows to “bow” before the audience, grateful for the chance to go slack.

GRAND FEAT complete, she lets her apple, only slightly bruised, roll away.

In the late nineteenth century, conventional wisdom held that elephants possessed a sixth sense for danger and would refuse to cross unsafe ground. To demonstrate the stability of their structures, engineers would make elephants walk across new bridges.

On June 14, 1874, the Eads Bridge passed “The Elephant Test.”