Hehua

by Millie Ho

Illustrated by | Edited by Julia Rios

January 2018

After ignoring her for weeks, I find out that Hehua was murdered behind New Finch Station. Coffee burns down my fingers and splatters onto the conference table, but no one glances back at me.

“We’re looking for information that will help us learn more about Ms. Liang’s life in Toronto,” the detective says, his eyes that shade of seawater blue that’s often seen in Wonder Kids in their mid-thirties, a popular option back then. Behind him, my manager Swanson rubs his own seawater blue eyes, a perfect carbon copy that would have you mistaking them for brothers if your stomach didn’t knot at how artificial everything is. “When your name is called, please follow me into the interview room.”

While we wait, my consultant coworkers huddle together, their Wonder Kid minds churning out possible motives and theories at a speed I can’t even imagine. One of them taps my shoulder and asks me a question I don’t hear, and then I’m in the bathroom, feeling the walls close in on me, my heart beating in my jaw.

I think of all the texts Hehua sent me, still unread. I cup my hands over my mouth, my teeth chattering way too fast, and then I’m spewing coffee and bagel all over the sink.

Hehua came to our management consulting firm a year ago, just when I was starting to worry they were replacing all the consultants with Wonder Kids. She had a small oval face and spoke broken English, but she smiled a lot and didn’t seem to mind that she was to work with me in the back, slapping data into PowerPoint decks so that our charming, fast-talking Wonder Kid counterparts could look good in front of clients.

When I visited Ba in prison and told him this, he’d smashed his cigarette on the glass between us. This was back when he was bolder, before they started strapping him down and Editing him.

“They pulled the same shit on me at the firm,” he’d said. “I should’ve been in the courtroom, but they said I’m not presentable enough. You believe that, Cassie? Twenty years as a lawyer, and I’m still back there filing papers. Fuckers. They deserve what they got.”

Hearing Ba talk about the arson made my palms sweaty, so I cleared my throat. “What if you’d gotten an Edit? I’m actually thinking of getting an Edit to get rid of my anxiety. Maybe my coworkers will like me then, heh.”

And Ba shut down, his stare turning hard, his upper lip rising.

The panic rose in my throat; Ba’s silences always did that to me. “I mean, I know Edits aren’t perfect, but if I got a minor one, maybe the good effects will outweigh the bad—”

“Go ahead, if you want to be a corporate bitch,” he’d snapped. “Just don’t come crying to me when you forget your own name.”

Ba’s words rang in my ears whenever I thought about getting an Edit. Maybe he was right. Edits could rewire your entire adult brain, take away your road rage, turn you into a Jeopardy! champion overnight. But they were less reliable than the Wonder Kid procedure, which created designer babies for the one percent, the ones with a boatload of cash to burn on perfectly intelligent, athletic, and beautiful heirs, with choice of skin and eye colour laid out on a self-serve menu, all risk of disease trimmed off their genes before birth.

Edits were for desperate adults and often hit or miss. Sometimes, while walking through the Financial District, I’d see someone get out of an UberPod in a jerky, lopsided way when they were fine just days ago, or say hi to a familiar face at a Starbucks, only to see their glazed eyes slide right off of me, having forgotten all about me.

“The world is getting Edited,” I told Hehua once. We were sitting in the food court far from the Wonder Kid cliques, our seating arrangement an exact replica of our work space upstairs. An ad for an Edit that got rid of anxiety flashed on the TV, which made my teeth ache with temptation once again.

“Wo bu xi huan Edits, they’re so super fickle,” Hehua had said, blowing on her pidu noodles. She giggled when I told her it was actually pronounced “Superficial”.

“Don’t you want to fit in?” I said.

“You should just be you,” Hehua said, then dipped her head over her bowl and slurped loudly.

I thought about what she said. Hehua and Ba both hated Edits, but Hehua wanted to be herself, while Ba was just angry at the world.

Eventually, I decided I liked Hehua’s reasons more.

She chatted loudly in Mandarin with her Nanjing relatives during breaks, shared funny cat gifs in our firm’s Facebook group, and even convinced me to go all the way up to New Finch Station and watch Korean dramas in her tiny apartment, our feet dangling off her futon, our lips smeared with chocolate Pocky. For Secret Santa at work that year, she gave a Wonder Kid coworker Hello Kitty socks, then lifted her dress pants to show a matching pair on her own feet.

She was wholeheartedly herself, and I loved that about her—right up until she decided not to be.

Two days after learning about Hehua’s murder, I finally work up the courage to look at her text messages. My hands shake and I have to wipe my palms a couple of times, but once my thumbs start moving, it’s hard to stop.

荷花 (hehua):

hey how r u?

荷花 (hehua):

Cassie why r u ignoring me?

r we still friends?

You stabbed me in the fucking heart, I wish I can tell her. Even now, my eyes burn when I think about the last time I spoke with her.

Edit. She had gotten Edited.

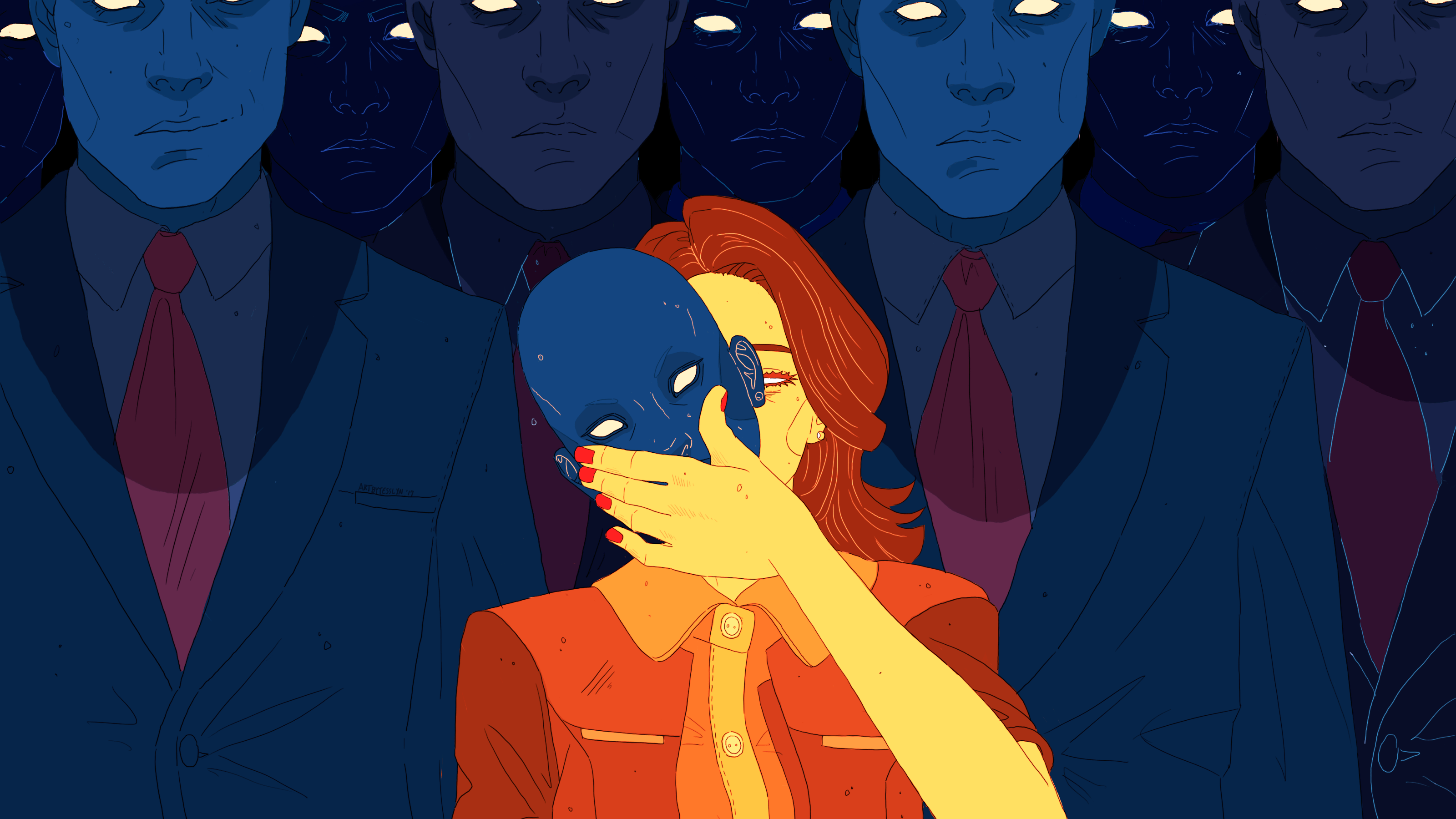

She had come to work one day with sleepy eyes and a soft smile, pushed back her bangs to show me the small curved scar on her temple, which gave her perfect English but also took away her Mandarin, an unintentional side effect. As she talked, I surprised myself by wanting to burst into tears. In the weeks that followed, I’d realize why: when she Edited herself, it felt like she’d Edited me, too.

荷花 (hehua):

r u mad because of my Edit?

;_;

荷花 (hehua):

ok

it’s Travis, I’m kind of seeing him

he told me to get rid of my accent

but now he’s trying to get rid of me

I know ur disappointed in me

I’m sorry, ok??

Who the hell is Travis? I glance over my shoulder to make sure no one’s looking, then go on Facebook to search Hehua’s friends list. I don’t recognize anyone until I come across a name that makes my breath die in my lungs: Travis Swanson. In his Facebook photo, he’s on top of a white hill, snowboard in hand, blond hair curling around his glowing face like a halo. A woman just as magazine perfect stands beside him, both of them looking like they barely broke a sweat, their gloved hands clasped together.

It’s Travis, I’m kind of seeing him.

I’m stunned into silence for the rest of the day. I chew my bagel without tasting it, the food court noises fading into the background, cold sickness curling in my stomach when I think of the article that detailed how Hehua was found: strangled with her own purse straps, no witnesses, a mugging that ended in tragedy.

Purse. Hehua always carried a backpack, then switched to a Prada purse out of nowhere. I don’t remember when the switch happened, but I do remember the ramen she fed me for breakfast after our sleepovers, that she would rather walk in the cold instead of shelling out for an UberPod. She was always frugal—and then she had a Prada purse.

I drop my face in my hands, blinking fast in the clammy darkness, wondering how many other clues I’d missed.

I start watching Swanson at work. The bright smile he wears is now shark-like, and the jokes he cracks during briefing meetings now feel planted, his laughter too pitch perfect.

At lunch, I hover around the break room, where Swanson is known to take calls, and slowly slather hummus on a bagel while tucking away bits of his conversations to dissect later. But most of his calls concern work, golf, or weekend trips with his wife. There’s nothing that implicates him, but I won’t give up until I find something.

One day, I’m halfway down the hall with a bagel in hand when I hear: “You all right, Cassandra?”

Even when I’m not facing him, Swanson’s voice is still affecting, a smooth and rich sound that reminds me of an ice cream commercial. I whirl around and he’s way closer than I expect him to be, close enough for me to smell his spicy cologne and see the lack of pores, the lack of wrinkles, the lack of everything that indicates he’s anything but a Wonder Kid who’s reached physical perfection.

“I know Hehua was your friend,” Swanson says, and I can’t deny the sympathy in his voice. “Let me know if you want time off. It would be good for you to mourn properly.”

What about you? I want to scream. Don’t you want time off?

Instead, I say, “Do you know if she was seeing anyone?”

Those seawater eyes flick left-right-center, a quick, barely-there movement. “That’s an odd question to ask me, Cassandra.” He places a hand on my shoulder, his fingers warm. “Why don’t you talk to the detective? Akachi’s a good guy, caught more crooks than I closed clients. So talk to him, relax, and get rid of those dark circles. The cops are working hard.”

I turn to leave, but Swanson’s grip tightens on my shoulder. He’s peering deep into my eyes now, and despite forcing myself to see him differently, I still feel the ugly yearning I have for all Wonder Kids who ever gave me their complete attention. “And hey,” he whispers, “if you really want to take your mind off things, I can take you to get Hovered. There’s a nice place on King West. Just let me know.”

It’s the longest conversation we’ve ever had, and everything about it feels surreal. The urge to ask if he killed Hehua drives me mad, but soon I’m out of his grip and in the bathroom, splashing cold water on my face, slapping myself awake.

I can take you to get Hovered.

Of course he’d suggest Hovering, the fucker. Because all people like me escape their problems by getting their minds scrambled.

My stare turns hard in the mirror. If he wants me to talk to the detective, I’ll call his bluff.

At the police station, I get straight to the point and hand Akachi my phone. He scrolls through the texts, his eyes, like Swanson’s eyes, flicking left-right-center as he processes the information.

“It’s all circumstantial,” he says finally, sliding the phone back to me. “Yes, it suggests there was a relationship, but there’s no motive.”

“There is motive!” I say, and show him Swanson’s Facebook profile. “Look—he’s got a wife. Hehua said Swanson was trying to get rid of her. He could’ve strangled her to keep her from talking to his wife.”

Akachi smiles a slow smile. “Wonder Kids make mistakes, but we don’t murder people. And Mr. Swanson has an alibi for that night.”

“Does his wife know about the affair?” I snarl.

Akachi’s smile drops. “Let me repeat myself: Wonder Kids don’t murder people. It’s scientifically impossible.”

I shoot up from my seat. “You’re a shit detective, you know that? You guys only enforce one kind of justice—your own. You know nothing about the struggles of normal people.”

Akachi stands up as well. “I know plenty, Ms. Xu. You know what people sacrifice to have a Wonder Kid?” He pushes aside his blazer and points to his lower back. “My father gave up his kidney, for one. I know all about the struggles of normal people, but also what it costs to be valuable in our society.” He sits back down, his nostrils flaring. “There’s no way such a heavy price would produce a murderer.”

For once, I see how maybe Akachi’s seawater eyes don’t go with his full lips and thick, textured hair. Even his skin colour seems off—it’s too light, almost washed out.

But he’s smiling again, leaning back in his seat with his hands clasped behind his head. Just enjoying how different we are, watching me like I’ve come specifically to remind him of this.

“Fuck you,” I say, and turn to go.

“You’d be wise to check your temper,” Akachi calls after me. “You don’t want to end up like your father!”

“Come to my office, Cassandra.”

Swanson leaves the doorway as quickly as he appears, his Rolex watch flashing as he shifts out of sight. I stare at my blinking cursor for a few seconds, then wipe my palms and stumble down the hall.

In his office, Swanson stands facing the window, his hair burning gold under the afternoon sun. He turns around, his face glum, and flips his holoscreen toward me.

Hehua Liang Murder: DNA Phenotype Report Leads Police to Killer

I gasp. I scan through the article with lightning speed, but instead of Swanson’s photo, I see a high, pimply forehead and sunken eyes. The man—Theo Frank—is not a Wonder Kid, though he was Edited unsuccessfully for a mental disorder. And he’s already confessed to the murder.

“I wanted you to be the first to know.” Swanson’s shadow cloaks me, his spicy cologne overpowering. “I’m so sorry, Cassandra.”

“Why?” My voice is croaky, and I’m not even sure what I’m asking. This has to be a setup. Swanson killed her. Wonder Kids can commit murder—they CAN.

“Who knows what goes on in the mind of a psychopath?” Swanson swipes to an ad for a clinic that does Edits to get rid of trauma and grief. “Give this place a try. Everything will feel like a bad dream, and you can start a new chapter in your life.” His grip is hot on my shoulder. “It pains me to see you suffering so much, Cassandra. Heck, I’ll even pay for the Edit. Why don’t you take some time to think it over?”

I open my mouth, then close it. There’s nothing left for me to say, and when I look up at Swanson, I see that he knows it, too.

The visitation room smells like bleach. Ba’s looking thinner than I remember, almost completely bald now, his smile skeletal. I wince when I see the angry strap marks around his wrists, the many curved scars stamped on his temples like leeches.

Ba leans his forehead against the glass, and the guard behind him shifts forward, a subtle warning. “Did you bring my smokes?” Ba says, attempting a wobbly smile.

I shake my head. “Ba—”

A whine rips from his throat. “Then what are you good for, Cassie, huh?” He lowers his head, and his shoulders shake like he’s about to cry. “What are you good for, huh?”

I try to keep my voice even. “Ba, something terrible has happened, and I need your advice. Should I get Edited to get over it—”

“CORPORATE BITCH!” Ba slaps the glass, his open mouth revealing newly missing teeth. The guard shoots forward, aims a Taser in Ba’s face, and Ba immediately recoils, both hands cupping his mouth to muffle his cries. My face burns to see him like this, this once outspoken man crumple up the second you flash a stick in his face.

“That’s a wrap, Mr. Xu,” the guard says, planting a big, gloved hand on Ba’s back. “Say bye to your daughter now.”

“I WANT MY SMOKES!” Ba shouts, letting himself be pushed away, his voice cutting off when the doors slam shut behind him.

I walk out in a daze. When I turn into the hall, I bump shoulders with a woman who jostles past me. Her face is wet and contorted with ancient rage, and despite her deep wrinkles, those sunken eyes look vaguely familiar.

“Theo’s innocent!” I hear her yell. “Don’t you dare take my grandson away from me, he’s INNOCENT—”

And then guards march into the visitation room, visors pulled down, Tasers raised.

I don’t stick around for what inevitably follows. Even though I didn’t get a chance to ask Ba my question, I walk out of the prison gates feeling like I have all the answers I need.

All over downtown, holoboards advertise Edits, each claiming to be an improvement of the last.

I grab a bowl of pidu noodles in Chinatown, and watch the neon lights blink around a new Edit that helps you get rid of sex addiction. Another so-called instant fix, the product of all the experiments done on Ba and other prisoners who were sentenced to be Edited and Edited until they were no longer deemed a public threat.

I walk over to Yorkville, where Swanson lives, in one of those restored Victorian houses on a street lined with solar trees. I wait until Swanson’s black Benz turns into the gated driveway and Swanson and his wife get out, Swanson in a tux and his wife in a silver dress with a matching fur stole, both of them looking fresh from a ritzy restaurant or concert hall. Just getting on with their lives, just another Saturday night.

So super fickle, as Hehua would say.

A hot rage stabs through me, and I know what to do.

I walk into Swanson’s office feeling like I’m set on fire, all anxiety burned off my body like dead skin. Swanson looks up from his desk and removes the cigar from his lips.

“Cassandra,” he says, and the rich cadence of his voice no longer makes me want to lean in. “Have you made a decision about the Edit?”

“Let’s get Hovered, Travis,” I say, and his eyebrows rise at the use of his first name. “And then I’ll get Edited.”

He looks at me carefully now, suspicion clouding his eyes. But I smile like Hehua would, and he relaxes, his shoulders drooping.

“Well, I suppose it’s good to chill out first,” Swanson says, then presses a button to tell his secretary to cancel his evening appointments.

As I follow him into the parking lot, I watch the way his shoulder blades shift under the wool fabric of his suit, and finger the knife in my purse.

The windows of his Benz are tinted pure black, and as he starts the car, I wonder if this was where it happened, if I will find a Prada purse in the trunk, flecks of leather falling off the straps where they cut into Hehua’s neck the hardest.

I shudder, but can’t backpedal now.

“Are you sure about this?” Swanson’s voice is soft, but I don’t miss the edge shimmering under the words.

“I’m sure,” I say, and awkwardly put my hand over his.

He stares down at our hands, his lips parted, expression almost vulnerable, and I wonder for a second if I’ve got him all wrong.

But then he looks up and I see the entitlement swelling in his eyes.

“Good,” he says, and I hear the click of the door locks just before he swoops down.

Terror flushes through me—I pull my hand away but he slams it against the window, shooting pain down my arm. Hard elbows stab my stomach, and I taste bile, can’t breathe.

“Think you can trick me, you silly cunt?” Hot fingers clamp around my neck, and I’m kicking and clawing him, but there’s too much pressure in my head, too much blood roaring in my ears, and too much distance between my fingers and the knife. “I could feel you trembling from a mile away—”

I choke as the pressure leaves my neck, my lungs bursting with relief. Black dots swarm my vision as strong hands tug me up. I flinch away, but the hands refuse to let me go, and then I’m staring into seawater eyes—Akachi’s eyes—through the swirl of my own tears. He’s saying things, but I can’t hear anything over the howling of Swanson and the crackling of Tasers.

Knock-knock.

Through the peephole, Akachi looks almost normal in a leather jacket and jeans, Whole Foods bag in hand. I scan my thumb and unlock the door, and he grimaces when he steps in. “No turtleneck, huh?”

“Why hide it?” I say. My voice is still raspy, but at least it’s still there.

It’s been a week since the attack, and after the doctors and reporters have left, I holed myself up in my apartment, eating mashed bananas, trying to sleep, avoiding going outside in case Swanson was in the hall, swinging a hatchet. Akachi hasn’t contacted me until this morning, to tell me that he needs more details for the case against Swanson.

“He’s going to get Edited,” Akachi says, walking into the living room. “It’s a first for a Wonder Kid.”

I hug my chest. “And Theo?”

“Ms. Liang’s case is closed,” Akachi says, playing with a ribbon on a get well basket sent by an Anti-Editing advocacy group. “Orders from the higher-ups.”

I dig my nails into my elbows. “Then why are you here, Akachi? Didn’t you want more details for the case?”

“I said that to cover my tracks.” He lifts something out of the Whole Foods bag and hands it to me. It’s my purse, unzipped with the knife handle still peeking out.

I feel cold. “That’s—”

“Take it. I won’t say anything.”

He’s glaring at me like it’s an unbelievable chore to have to do this for me. So I put the purse away, tuck it behind my closet with the blazers and pantsuits I decide, just now, that I no longer need because I’m going to quit my job.

When I come back, Akachi’s looking at the framed photo of me and Ba on the TV stand, the one taken at my university graduation barely a month before the arson.

“You know why I helped you?” he says. “Hubris, Ms. Xu. I was so sure you didn’t know shit. But the longer I trailed Swanson, the more cracks I saw, and then I caught him—you know.” He smiles slowly. “But I guess I saw my father in Theo Frank, too. Dad also had a botched Edit, thought he could redeem himself by having a Wonder Kid. Crazy, huh?” He heads to the door, steps into his loafers. “But like I said, the case is over. You should move on.”

After Akachi leaves, I curl up on the couch, my fingers grazing my neck, which is still sore. I watch the sun sink through the blinds, the ceiling burning gold, then dark red, then violet. I stay still for a long time, the apartment dimming around me, rush hour traffic stirring down below.

Finally, I turn on the TV.

Theo’s grandmother is on CTV News. I fear the worst, but then I realize she’s being profiled. Her face is bruised, her beehive hairdo slumping over one swollen eye, but she’s still speaking animatedly to the reporter. The camera pans to New Finch Station, where people are lining up to sign her petition, some holding up picket signs demanding an appeal of Theo’s conviction, others demanding justice for Hehua.

I feel the walls expand around me. This case is far from over.

I pull on my coat. After taking a deep breath, I step outside.