Emerald Lakes

an Atlanta Burns story

by Chuck Wendig

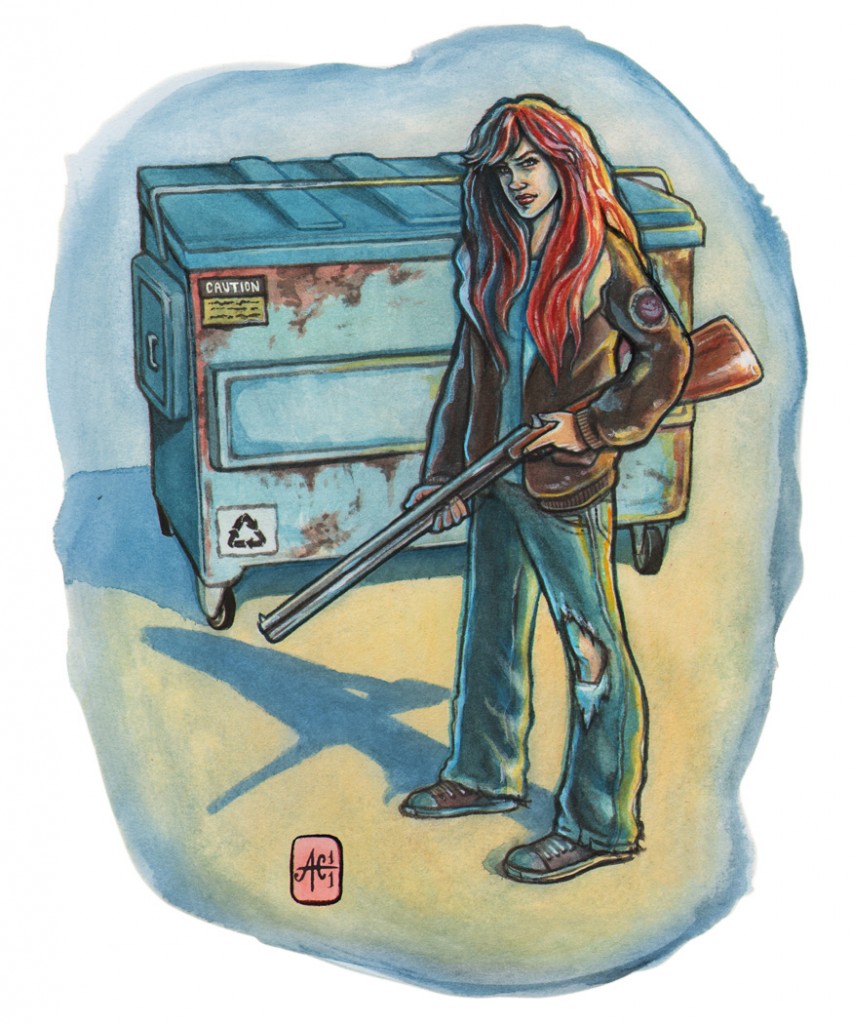

Illustrated by Amy Houser | Edited by Brian J. White

March 2012

THE NAME is a lie; no lake or lakes exist here. Outside it’s just a parking lot, some trees, a well-manicured lawn with the light-and-dark stripes mowed into the grass. And the walls are more a seafoam green than emerald. But life is easy in the Emerald Lakes facility. They don’t ask much here. Don’t miss therapy. Don’t miss rec time. Go to your room when the first tone plays, lights out by second tone.

Oh, and take your pills. Always take your pills.

ATLANTA TAKES her pills. At first.

She’s three weeks into a three-month stint. Eating alone again. It’s not like she’s some freakazoid and nobody wants to talk to her — other girls have come and gone, but the next day she finds a new table by herself and sits there because that’s mostly what she wants to be: by herself.

She spears a too-crispy tater tot and pitches the potato barrel into her mouth. Crunch, crunch. Ick.

All around her, an array of damaged girls sitting at other tables. Atlanta’s a junior in high school, and all these girls are around her age. Fifteen to eighteen. Becky Moynahan — the insides of her forearms reveal a ladder of pink puffy cuts. Missy Eckhart — rented herself out like a DVD and fucked a bunch of older dudes above her parents’ garage. Alice Kucharski — ate all the pills in her mother’s medicine cabinet, spent two weeks in a coma, almost died, didn’t, now she’s here expected to eat the right pills so she stops swallowing the wrong pills. Over there: stole Daddy’s car, ran it into an elementary school. Across the room: stole horse tranquilizers from the farm vet. So many others.

I’m not like them, Atlanta thinks.

By the doorway to the cafeteria she sees one of her counselors. Miss Flaherty. Puffy hamster cheeks. Helmet hair like maybe it came off a LEGO figure. Nice lady. Got a bouncy wobble to her.

She sees Atlanta. Makes a motion with her hand and mouths some words. Atlanta can decipher the intention well enough: Go mingle with the other girls!

Mingle being Miss Flaherty’s word.

Atlanta pretends she doesn’t see the woman. Instead takes a tater tot and drowns it in ketchup, then mustard, then grumpily chews it. Wishes it were a hush puppy, but it’s not. That’s not really a thing they do here. Here being up north. Pennsylvania. And nobody here can make fried chicken worth a lick, either.

Wham.

Someone slams a tray down next to her. Loud enough so that it vibrates the table but not so loud it draws an orderly. It’s Lakesha Spitzer. Lakesha’s what the other kids at school call an Oreo: up here they mean she’s half-black, half-white. Down South it meant something a little different, but whatever. Girl’s got features so severe you could open a can on that chin, could cut glass with those elbows, might lose an eye near those cheekbones. She smiles as she sits down next to Atlanta.

It’s the smile of a fox or maybe a wolf.

“Hey, Lakesha Spitzer,” Atlanta says.

“‘Sup, Atlanta Burns,” Lakesha says, but it ain’t friendly. “I hate that name.”

“So you’ve said.”

“Look at you. Sittin’ over here all by your lonesome.” Lakesha grabs one of Atlanta’s tater tots, eats it. “You think you’re a tough-ass bitch.”

“No,” Atlanta says, “I don’t.”

“You frizzy-hair red-headed cracker bee-yotch, I said, you think you’re tough-ass.”

“Okay. Uh-huh. Tough as last night’s chicken.”

Lakesha watches her. “We all know what you did to get in here.”

“I know you know.” She knows, because they talked about in group.

“You think you can take me?”

“What answer you want me to say? No, don’t hit me? Yeah, I can knock your tits off? Lakesha, I just don’t give a shit right now, okay? Why you so mad? Ain’t nothing between us but the air we share.”

Lakesha responds by taking all of what’s on Atlanta’s plate — tots, ketchup, mustard, a dry-yet-somehow-soggy chicken thigh — and, when nobody’s looking, dumping it in Atlanta’s lap.

Then she wipes her messy hand on Atlanta’s sleeve.

“I’m gonna get you yet,” Lakesha says.

And then she’s gone, leaving Atlanta a mess.

PILL-TIME.

The pills aren’t anything heavy-duty. Not for Atlanta, anyway. In the cup they give her she always finds a little pink one shaped like a home plate diamond and a bigger blue one. Like a little Frisbee.

She takes them, she mellows out. It rounds sharp edges. Cork on the end of a fork.

They don’t help her forget what happened.

But they make her not care, and that’s good enough for now.

THEY GIVE THE GIRLS phone privileges once a day.

Make one phone call. No more.

Atlanta hasn’t used her privileges yet. Which means she hasn’t spoken to her mother yet. She’s been by a couple times, her mother. Wanted to have a visit with her daughter.

Atlanta denied the visits. She couldn’t do so outright — she’s still a dependent, after all — so she faked being sick. Not cough-cough sick but I’m-in-the-bathroom-and-can’t-come-out-sorry sick.

It worked. Arlene went home.

Now Atlanta thinks to finally use her phone privileges and so she picks up one of the three phones they have against the wall. She doesn’t call her mother. Instead, she calls her friend, Becky Bartosiewicz — AKA, “Bee.”

Ring, ring, ring.

Click.

Bee’s mother.

Atlanta asks to speak to her friend. Not her only friend, but her best friend, her first friend — at least, first since moving up here from down South.

“I’m sorry, Atlanta,” Bee’s mother says. “She’s, ahh, she’s out.”

“But it’s just past dinner,” Atlanta says. Bee’s never allowed out after dinner on a school night. Chores. Homework. No going out. “Where’s she at?”

Bee’s mother says nothing at first. Atlanta can hear a sound that might be the woman chewing her lip or the inside of her cheek. She must not know how to keep up the ruse because finally she says, “I don’t think she wants to speak to you, Atlanta.”

“Why?”

“I think it’s best you don’t call her anymore.”

“That’s not an answer.”

Bee’s mother hangs up.

That woman’s always been nice as cookies.

Which makes this doubly jarring.

The next day, Atlanta’s back at the phone bank. Waits in line for a half-hour, gets to the phone. Calls Bee’s cell phone. Every kid at school has a phone (some of them have more than one, cycling through disposables the way other kids change clothes), even Bee. Atlanta’s never had one, but whatever.

It rings a couple times, then goes to voicemail.

Atlanta tries again. This time, no ring. Again to voicemail.

She doesn’t bother leaving a message. Instead she just blinks back some tears so fast it’s like they were never there and leaves the phone for the next girl.

LAKESHA’S WATCHING HER during group. Watching her the way a hawk watches a squirrel cross the road.

Right now, Fiona Maguire’s talking, telling some story to all the girls in the chair circle — “First time I let someone close to me it was Petey Woodworth, I let him finger-bang me on a bench up on Dave Hill — that’s Earl Davis Hill, part of Earl Davis Park for those of you who don’t know Frackville real well, but we just call it Dave Hill because I dunno you know whatever it’s funny — and he was nice to me I guess but he probably was the last one that was nice to me and after that it was just a bunch of guys who treated me like I was a, uhh, a, an, uhh, you know —”

Way Fiona talks it’s like she’s got popcorn popping in her mouth. Barely a breath between words. Just that constant rat-tat-tat. Atlanta figures she’s trying to explain something about her eating disorder — Fiona’s a binge eater and a bulimic, her weight going up and down like a bungee jumper — but all Atlanta cares about right now is the way Lakesha’s staring daggers and darts at her.

Miss Flaherty’s doing what she does best: mm-hmming, nodding, steepling those fingers.

Atlanta can’t help it. She interrupts.

“Sorry, sorry,” Atlanta says, waving her hands. “Don’t mean to interrupt. I just need Lakesha to stop staring at me. If I’m being honest, it’s freaking me out. Lakesha: quit it.”

“Girl can look wherever,” Lakesha says. “Ain’t illegal to have eyes.”

“Ladies,” Flaherty says, obviously unaware of what that word means, “Fiona is telling us all a story.”

“No, it’s okay!” Fiona chirps. Then leans in like she’s about to watch a scary movie.

“Whatever,” Atlanta says. Under her breath, she adds: “Stare at me, then.”

“I fuckin’ will.”

“I see that.”

“Ladies,” Flaherty says again, this time more insistent. In the back of the room, the orderly on duty — big Hawaiian-looking dude named Henry Ko — tenses up in case he needs to step in.

“You don’t like me looking,” Lakesha says, “then do something about it.”

“I’ve made my peace with it. Go on, do what you like.”

“Ooooh. Girl ain’t so tough without her gun. Is she?” Lakesha crosses her arms, sticks out that icepick of a chin. “Or maybe it’s that I don’t got no nuts to shoot off. That the problem, Ata-lanta?”

Orderly Henry takes a few steps forward when Flaherty gives him the nod.

“I need to go,” Atlanta says. “Can I go?”

“Little bitch,” Lakesha hisses.

“Lakesha,” Flaherty says, standing up. Henry moves fast, comes up behind Lakesha like a silent tsunami. He doesn’t touch her. Not yet. But the way his shadow falls tells everyone what’s up. “You will respect the other girls in this circle. You’ve already got an impressive list of demerits on your chart, and I’m about to start adding more. You want more privileges gone, just say the word.”

“Naw,” Lakesha says. “I’m good.”

“Atlanta, you can go back to the rec lounge. But we need to do a private session later.”

“Shit,” Atlanta says. “I mean — yay, okay, sure, fine.”

IT’S ABOUT AN HOUR later that Atlanta sees something. Something that makes all too much sense. There she sits in the rec lounge reading a copy of the Count of Monte Cristo (they don’t have a television here because nobody ever wants to watch the same thing and next thing you know you got a bunch of crazy girls clawing each other’s eyes out because one wants to watch Teen Mom and another wants to watch Seinfeld reruns). Group ends. The girls spill out buzzing with energy like they always do — you talk for an hour about all your problems, and it’s like spraying bug killer down a yellow jacket hole. Stirs everything up a good bit.

Lakesha doesn’t see Atlanta, not yet, but Atlanta sees her.

She comes out and goes into the little mini-fridge and pulls out a Capri-Sun juice bag. Lakesha drains the thing into her mouth with a single squeezing fist and then heads to her room.

But someone else besides Atlanta is watching.

And that someone follows behind Lakesha.

And that’s when Atlanta starts to understand.

Atlanta gets up, thinks to follow along, too. But a throat clears behind her and there stands Flaherty.

“This ain’t a great time,” Atlanta says.

Flaherty clucks her tongue. “Sorry, Miss Burns, but it’s an excellent time for me. C’mon. Let’s talk.”

OF COURSE, Flaherty wants to talk about her mother.

Flaherty’s office is a mess. Papers everywhere. Books, too. A corkboard on the wall is so cluttered with push-pins and receipts and charts that it hurts the eye just looking at it.

“You’re mad at her,” Flaherty says. “It’s okay. You’re allowed to be.”

“Who said I was mad?”

“You have every right to be.”

“That’s good to hear but it doesn’t matter because I’m not mad.”

“Atlanta. Come on now. She invited him in. She let him into your life. And then what happened, happened. I know for sure that I’d be mad.”

Atlanta shrugs. “I must be a higher life form or something then. Like maybe I was reincarnated from a cow and now as a human I have found peace. The Indians — uh, not the tomahawk Indians but the ones with the dots on their heads — believe cows are sacred. So maybe I’m just a cow. A happy peaceful docile cow who ain’t mad at anybody.”

“You shot your step-father,” Flaherty says, those words heavy and solid like a rock dropping into a pond. Or maybe a turd dropping into somebody’s iced tea. Splash.

“I didn’t kill him.”

“No, but you … changed him.”

“Oh well. Maybe he shouldn’t have touched me, then.”

“That does not sound like the attitude of an evolved higher being.”

“Yeah. I guess not.” She takes a pen rolling loose on Flaherty’s desk and pushes it back and forth. “I’m still not mad at her no matter what you say.”

“So stop faking sick and let her come visit you.”

“Maybe.”

“Maybe?”

“Maybe.”

Or maybe not.

IT’S THE NEXT DAY that Atlanta starts hoarding her pills. It isn’t hard. The other girls do it all the time. Can’t tuck ‘em under your tongue because they sometimes check there. What you do is offer a little misdirection — Atlanta likes to crumple the cup because it’s noisy and it draws the eye to her hand and not her face — and while they’re looking that way she uses her tongue to tuck the pills in the back of her mouth. Sandwiched between the inside of her cheek and her bottom gums.

Then she hides them in her bra.

OVER THE NEXT couple weeks she keeps an eye on Lakesha when Lakesha’s not keeping an eye on her. Shadows her after group or meal-time. It’s not every day that she sees what she sees. Maybe every third or fourth day. But it’s not just a one-time thing. It’s often enough to confirm what Atlanta’s afraid of. And now she gets it. She really gets it. Dangit.

ATLANTA’S IN the bathroom washing her hands when Lakesha catches her.

“You been watchin’ me,” Lakesha says.

“What’s good for the goose.”

“What’s good for the goose what?”

“It’s a saying. What’s good for the goose is good for the gander.” Atlanta shrugs. “I don’t really know what geese have to do with anything, but it means that you’ve been watching me so now I’ve been watching you. Quid pro quo, tit for tat, blah blah blah.”

“You think you’re so smart.”

“Smart enough to figure out what’s going on.”

“The fuck you mean?”

“I mean you and that orderly are messing around.” Not Henry. The other one on day duty. They call him Pecker because his last name is Packer and everyone thinks it’s funny. But suddenly it isn’t funny at all. “But the way he looks at you and follows you I don’t think it’s exactly mutual.”

Lakesha chews on her lower lip the way you might gnaw on a strip of beef jerky. Like maybe she’s trying to draw blood so as to distract her mind from thinking whatever it is she’s thinking. But the look on the girl’s face tells Atlanta she’s right. And the way Lakesha’s hands ball into fists tells her that’s maybe not such a good thing.

“You’re fuckin’ dead,” Lakesha says. With the back of her foot she slides the trashcan in front of the door. Not enough to prevent anyone from coming in, but it’ll slow them down, give some warning at least. And the bathroom is one of the two places in this whole facility that doesn’t have a camera in it. Here and in the girls’ bedrooms. State law and privacy legislation means they can’t watch girls in a place like this. Prison, yes. Mental health facility, no. “Saying shit like that about me.”

“You know you’re not pissed off at me. But you want to take it out on me, go ahead.”

Lakesha grabs her. Jacks Atlanta against the wall next to the towel dispenser.

And then she does nothing.

Just waits. Breathing. Nostrils flaring. Chewing that lip.

They wait there so long, Atlanta starts getting a little bored.

Finally, Lakesha says, “Is it true?”

“Is what true?”

“What you did. To get in here.”

“It’s true.”

She lets go of Atlanta.

Deep breath.

Then it comes out, like puke.

“Packer comes after me every couple nights,” she says. She looks down at the floor as she explains how he sneaks in right before the shift change. How he tells her not to undress, but just to open her mouth. How he moans and grinds his teeth and pops his knuckles as he pops his cookies. “I tried fighting him. But he’s strong. And he says that he’ll report me if I don’t do what he says. He reports me for anything, they’ll bump me up to juvie.” She finally looks up. “You can’t tell anybody about this.”

“I won’t.”

“You tell anybody, I’ll fuck you up.”

“I said I won’t and I won’t.”

“Yeah. All right.”

And that’s how they leave it. But Atlanta hasn’t really left it at all.

SHE SITS in her room, palms sweaty, heart going like a hummingbird trapped in someone’s pocket, and it’s then that she smells the stink of gunpowder hanging in the air — it’s not there, not really, but she hasn’t been taking those pills and now the feeling is starting to come back to her.

The memory of it crawls up inside her. The bang of the gun. The scream afterward. His and then hers. Blood in a dark room not red but black — a deeper dark against the shadows of night.

And here she wants to do it all again.

Around midnight, the door opens. Packer the Pecker comes in. He’s greasy, pale but for his pink cheeks, got long arms like monkey limbs framing his pooched-out gut.

He waves a little piece of paper around. “I got your note.”

“Good,” she says, forcing the word out — it comes out dry and cracked as the desert ground. Her hands are shaking. She wills them to stop. They do, but only because she presses her palms so hard into her knees she can feel the sweat soaking through.

Packer looks around, and laughs nervously. An unexpected social awkwardness rises. “So. Ahhh. How you wanna do this?”

“I guess I’ll … “ Again her voice dries up. Speak, talk, say something, say anything. “Guess I’ll get down on my knees.” He reaches for his zipper but she stops him by saying, “Can I have a kiss first?”

He smiles, a gee-shucks-gosh kind of look like he thinks she’s secretly sweet on him, and he says, “Well, sure, okay, if that makes it feel special for you.”

“My throat’s just a little dry,” she says. Not a lie. “Hold on.”

Atlanta reaches for a nearby cup, pretends to drink from it. Then she crunches the cup.

She stretches up on her tippy-toes and goes to kiss him.

He opens his mouth. His tongue seeks hers out.

And she spits a fusillade of pills down his throat.

Gotcha, you girl-touching sonofabitch.

Or so she thinks. He shoves her away and starts gagging. Reaches into the back of his throat with his own fat-tipped fingers and coughs loud and sharp —

The pills drop out of his mouth, glommed together with a sheen of saliva.

It didn’t work.

Oh, no.

“You crazy little fuck,” he says, still hawking and spitting to make sure he got them all.

This is it, she thinks. Her one shot, poorly played. And now she’s in a room with a rapist molester asshole and he’s strong and angry and she doesn’t have her shotgun and nobody will see anything because they can’t put cameras inside the girls’ rooms, only out in the hallway …

Only out in the hallway.

Packer reaches for her —

Atlanta pulls away.

Then punches herself in the face. Four knuckles smash hard into her nose and upper lip and teeth and the black behind her eyes erupts in a blizzard of bright white snowflakes —

“What the hell?” Packer says, taking a step back just in case he gets a little of the crazy on him. He says it again like he’s expecting an answer: “Oh, what the hell?”

Atlanta tastes blood. Feels it crawling down her nostrils, too, dripping from a nose that pulses and pounds like a kick drum.

He reaches for her one more time.

One last time.

She spits a mist of blood in his face, then throws open the door to her room and runs down the hall.

He comes after her — mad like a hornet, hungry like a mosquito, driven to the brink by the blue balls in his pants and the taste of blood on his lips, and as he rounds the corner, his face a mask of contorted rage, Atlanta falls to the floor, fake-sobbing and screaming, putting on the best performance she can.

He skids to a halt.

It’s then he realizes:

The hallway has cameras.

And he just chased a girl out of her room. Her face bleeding, his face red with her blood.

Packer turns the other way and bolts.

IT’S ENOUGH. It gets him not just fired but brought up on charges. The cameras catch everything. Atlanta has to sign statements. Maybe even go to court — though, given how sensitive the situation, Miss Flaherty says that it shouldn’t come to that. Atlanta has to sit in on extra one-on-one sessions with Flaherty, which isn’t ideal. But that’s a small price to pay. At least Flaherty’s nice.

The other girls like Atlanta even more, now. (Another small price to pay.) They think she’s some kind of bad-ass. She wonders if the girls back at school will feel the same way.

Atlanta sees Lakesha only in passing. They don’t say anything to one another, but the next day Atlanta gets a note under her door: Thanks for keeping an eye on me. –L

IT’S TWO DAYS LATER that Lakesha stabs another girl. Yolanda Bruin gets handsy at lunch and Lakesha sticks her in the offending hand with a fork. They have to drag Lakesha away kicking and screaming. It takes three orderlies, including Henry the big Hawaiian.

When it’s all over, Atlanta tells Miss Flaherty:

“I think I want to see my Mom now.”

Flaherty nods and makes the call.