Temperance

by Christie Yant

Illustrated by Amy Houser | Edited by Brian J. White

March 2012

IT WASN’T THE WORST BENDER of Anthony Cardno’s life, but it was the first that he had ended in a cemetery, vomiting into an open grave. His head throbbed; his mouth tasted of dust and sickness. He didn’t recall how he came to be here. He remembered the wagon that had carried him away from Santa Lydia, where he had quickly worn out his welcome, but he didn’t know which direction it had taken him and couldn’t guess where he might be now. As long as it wasn’t San Francisco, he’d probably be all right.

His flask lay out of reach, at the bottom of the freshly dug hole. He tried to roll over and rise, but his stomach rebelled, leaving Anthony to pray his usual prayer on mornings like these: Never again, O Lord, if only you’ll make it stop. But the Almighty had heard it all before, and Anthony’s stomach evicted its contents right into the grave. There was a ringing in his ears, and it wasn’t until the heaving stopped and he could breathe again that he heard the voices, angry and dismayed, and saw the rest of the scene before him: the grim marble markers that stretched out in rows all around him; polished leather shoes and long black skirts; the shaggy hooves of horses and the narrow wheels of a hearse wagon; and the shocked faces of the recently bereaved.

He tried to get to his feet but vertigo and drink still had him, and he tumbled over the side. He felt a rib crack as he landed hard at the bottom of the grave.

“I apologize,” Anthony said, the words coming out slow and muddy. “I apologize for disturbing your peace.” He retrieved his flask and did his best to rub the sick off it before tucking it back inside his coat.

“Get him the hell out of there.” The man who spoke stood out of view, but two young men — twins, by the look of them, with sun-faded hair, rolled sleeves, and ruddy, smirking faces — each reached a hand down and hauled him painfully over the side.

“What town is this?” he asked, and spit the sour bile that still lingered in his throat. “What day?” Those assembled stood in affronted silence.

A man stepped forward, stately and well-dressed in black hat and overcoat, a white flower in his lapel. An important man, by the look of him, but with a meanness in his eyes that reminded Anthony of his father.

“The wrong place, on the wrong day.” Anthony detected the familiar note of escalation in the air.

“I’ll just be on my way, then.” Anthony took several careful, uneven steps toward the track that led down the hill and toward the gates that he could just see beyond.

“Not just yet.” The man nodded at the pair who had pulled Anthony from the grave, and they moved in with swift menace. Each twin seized an arm and together they dragged him along, past the women who gasped and whispered behind their gloved hands, and out to the road where a row of buggies waited to carry the grieving home.

“Right there’s fine.” The boys dropped Anthony to the ground. “Stand up.” Anthony climbed unsteadily to his feet. The man stepped up to him and stood too close. “You stink of drink.”

“I meant no harm, sir.”

“My sister’s children will remember this day for the rest of their lives. So will I.”

And then he was caught again, held by the beastly twins while this man felt through his coat and searched his pockets, scattering his few belongings in the dirt. He had a moment of real fear when the man tossed his watch, and his attempt to pull away and go after it was rewarded by a sharp punch to the gut. The search continued until the man found what he was looking for.

The man pulled Anthony’s flask out of his inside pocket and held it up for all to see; then he pulled the stopper and poured the precious contents out into the dirt.

“I’m the mayor of this town, and I don’t want to know you. Get your things, and get the hell out of my sight.”

The mayor and his cohorts turned their backs on Anthony and started back toward the grave site. Anthony collected his possessions — pocket watch and watchmaker’s tools, unharmed; flask, empty; coins and notes, gathered and accounted for, despite the tremor in his hands.

“You asked what town this is,” the mayor called back over his shoulder. “You’re in Temperance. You might not care to linger.”

TEMPERANCE, CALIFORNIA — THERE WOULD be no relief for him in this town. Dry as a bone, surely, and righteous as hell about it.

The road into town was muddy and pitted with tracks, and the high winds whipped his face, cold and smelling of the sea. He twisted his ankle painfully before he’d gone a quarter mile; he limped past fields of plants cultivated in careful rows and past the dark-skinned Japanese immigrants who tended them. They took no notice of the dejected stranger trudging his way toward town, where maybe he could find a room for the night before boarding the steamer to San Francisco.

People were forever sending Anthony away from wherever he was. Bodie, Omaha, Leadville — he’d been through and driven out of them all. He’d go wherever they pointed him, generally, as long as it wasn’t toward home. He had reached the edge of town when he heard the slow, clip-clop crescendo of approaching horses as the funeral party returned from the hill. The party would overtake him soon; humiliation made his cheeks burn despite the cold. He shivered and quickened his pace toward the nearest shelter, a sturdy brick building with no sign to identify its purpose.

A door in the front stood wide open, but Anthony could see nothing in the darkness within. He took a step inside and was assailed by the heat. A furnace burned bright in the corner, and he recognized the trappings of a foundry: scrap metal in one pile, finished hinges and gadgets in another. He took a seat on a rickety stool, and within minutes the chill had finally left his bones, for what seemed like the first time since he’d been shut out of the comfort of his father’s house.

He pulled his watch from the safety of his coat pocket; it had been in the family for three generations. He’d had to buy his tools back three times now, but somehow Anthony had never lost the watch, nor sold it, nor had it stolen, nor gambled it away. He could say the same for nothing else in his life.

He opened the case with a soft click and held it to his ear. It was hard to hear above the roar of the furnace and the wind in the rafters, but the smooth tick-tick sound it made comforted him.

A sound from behind him made him jump to his feet. He expected to find the foundry owner, ready to accuse him of trespass and chase him out. Instead he found a young woman on her hands and knees in a pool of light from a source he could not see, feeling around on the dirt floor and talking under her breath. Her hair was a dark brown, and styled in a peculiar fashion: cropped boyishly short across the brow and the rest pinned back and curled under, falling only to her collar. What he could see of her dress was plain and shorter by far than was decent, but despite her apparent lack of modesty there was nothing slatternly about her — rather, he immediately felt as if he knew her. Her nose turned up just slightly at the end, and he knew that scowl she wore — of course: She was the very image of his sister Anna, who he hadn’t heard from since he began his wanderings three years ago.

Her hands searched frantically, and though she spoke too low for him to make out the words, he recognized the tone — the panicked pleadings of someone who is in a great deal of trouble.

He cleared his throat. The girl looked up at him, hazel eyes wide with surprise and fear.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to startle you,” he said.

“Shit,” she said. He reconsidered his early assessment of her.

“I beg your pardon?”

“You’re not supposed to be here!” That much was true; she had caught him trespassing and would now surely summon the smith, and Anthony would find himself once again at the wrong end of a fist.

“I’ll just be going, then,” he said.

“Sssh!” She gestured urgently for him to be quiet and looked back over her shoulder. She glared at him, shook her head, and then scrambled backward and disappeared into the shadows. A moment later the unseen light source winked out.

He crept forward to see where she might be hiding, but the corner was completely empty. The girl was gone.

A loud crash came from the opposite end of the open room — a second door swung open, and the shape of a broad, bearded man filled the doorway.

“You there!”

Anthony ran. Out the door and back to the road, his ankle sore and the pain from his cracked rib shooting through him like a bullet, but he did not stop. The man shouted after him. Anthony’s pounding pulse and the rasp of his own labored breath filled his ears. It was only when his pace slowed and he was able to catch his breath that he realized the man had been shouting, “Did you see it?”

He was exhausted and in pain, and now he found himself spooked and uneasy as well. What had he seen, exactly? He wondered if she’d really been there at all. It wouldn’t be the first time his mind had played tricks on him.

Right now he needed shelter, a room for the night, a hot meal, and — God help him — a drink.

THE FRONT ROOM of the hotel was a single open space, with a small check-in desk at the front opposite a lounge area and staircase, and past that, a few scattered tables and chairs. The room seemed over-sized for its purpose, as if in the planning of it the proprietor expected to seat a hundred instead of the two men who sat at the back of the long room. Another bitter reminder of his circumstances, there was no bar along the wall; just a pair of batwing doors in the back, probably leading to the kitchen. A wood stove just past the front desk warmed the room, and the scent of something meaty simmering in the kitchen made Anthony’s mouth water.

One of the gentlemen at the far end of the room rose when Anthony closed the door behind him — he was dark-haired and mustachioed, in sleeve garters and an apron, clearly the hotelier. The other, a short, bald man, looked as if he’d just come from a funeral — which, Anthony realized with a sick feeling, he probably had.

“That’s the one,” the short man said. The proprietor raised an eyebrow, and Anthony’s hopes for a safe haven sank. He turned to leave, but the door swung open again and he found himself facing the man he’d most recently run from: the metalsmith.

“You,” the man said, and grabbed his arm above the elbow, where painful bruises from the morning’s manhandling had blossomed. “Tell me, did you see it?” So he hadn’t imagined it. Anthony nodded. “Did it speak to you? Come sit, and tell me what it said.” He allowed himself to be pull deeper into the room, and took a seat at a table. “Now tell me.”

“About the girl? Who is she?”

“That’s no girl. Or if it is, it’s surely the ghost of one.” The man extended a scarred and calloused hand for Anthony to shake. “Mike Epple.” Anthony started to introduce himself, but Mike continued before he could get a word out. “You heard it speak? What did it say?”

“Nothing that I could make sense of.”

Mike hushed him as the hotel owner approached. “Harmon,” he said to the man.

“Mike.” Harmon nodded toward Anthony. “This a friend of yours?”

“We’re acquainted. Just discussing some business.”

“What kind of business are you in? Apart from making a mess of other people’s.”

Anthony shifted uncomfortably in his chair.

“Timekeeping,” Anthony said. “Watch repair.”

The bald man, silent during this exchange, stood and donned his hat. “I’ll leave you to your — guests,” he said. The front door scraped closed behind him with a sound that set Anthony’s teeth on edge.

“What are you serving tonight?” Mike asked. The proprietor folded his arms across his chest and gave him a hard look. “Harmon, have mercy. We’ve seen what no man should, and we need ourselves a damned drink. And whatever you’ve got in the pot for supper. I’m buying.” He clapped a pair of coins on the table. Harmon collected the money and retreated through the doors to the kitchen.

“That’s very generous — “

“What do you think it wants of me?” the smith interrupted, clearly agitated. “I’ve tried to be a godly man.”

“I think she may have lost something,” Anthony said. “She didn’t seem threatening.”

“Demons never do.”

Harmon returned with two bowls of stew and a pair of glasses, each with a finger of something amber and sharp. “You carrying on about your ghost again, Mike?” Harmon pulled up a chair and produced another glass.

Mike pulled something from his pocket and set it on the table. “I found this in the foundry. Maybe it was hers before she died, and that’s why she haunts me now.”

He handed the thing to Harmon, no bigger than a button. Harmon examined it briefly before passing it to Anthony.

“You didn’t make that, Mike?”

“Nah, I couldn’t possibly. It’s too fine.”

It was a polished brass lapel pin, skillfully cast and intricately detailed. The design was of a clock face: Roman numerals, one through twelve, and the hands marking the time at quarter to six. All the way around the edge were words picked out in careful relief: Temperance Society for Historical Preservation.

“Like the Ladies’ Society, I suppose,” Harmon said. “But we haven’t much in the way of history here in Temperance. Town’s only six years old.”

The door flew open and the two townsmen swiftly disappeared all three glasses under the table and onto the floor with a practiced ease. Framed in the doorway stood a tight-lipped woman of middle years, with an air of importance, and of menace.

She passed through the lounge and was followed by a dozen more women, each with something in her hands: rolling pins and broom handles, canes and clubs. They gripped and brandished them like weapons.

“Mrs. Finncutter,” Harmon said, hands up in a placating gesture, “what’s got your ire up this evening?”

“Good evening, Mr. Harmon.” She sniffed at the air and wrinkled her nose in disgust. “For your own safety and that of your guests I suggest that you leave us to God’s work, and the work of the Ladies’ Society of Temperance.”

“I can’t imagine what you mean, ma’am. I like to think I’m doing God’s work by giving shelter to those who need it.”

“This house is well-known to be unlawful, Mr. Harmon — a house of sin and temptation. You’ve been warned; the consequences are your own.” At her signal the women charged past: two tossed the contents of the front desk, two more marched up the stairs presumably to search the rooms, several more went straight to the kitchen, and beyond it, the stable. Soon the sound of barrels and bottles being shifted and overturned could be heard in the back room.

“You’ve no right!” Harmon’s face was red as a beet as watched his hotel destroyed. Anthony wondered what he should do; trying to stop them seemed foolhardy. Mike seemed to share his confusion. Harmon made a move toward the kitchen, where the sound of crates being upended could be heard, but just then two men stepped into the room: the bald fellow who had left not long before, and, to Anthony’s deeper consternation, the mayor. The bald man, still in his mourning clothes, held a rope in his hands. Harmon froze where he was.

Triumphant shouts of “We’ve found it!” came from the back. Anthony started to edge toward the front door, hoping to escape further violence.

“Stay right where you are.” The mayor leaned against the front desk and searched his coat pocket, and found what was he was looking for. “I’m surprised to find you here. I took you for a drunk, but not an idiot. If you were smart, you’d have been on a steamer to San Francisco by now.” He produced a pipe and box of matches. “But as you’re still here, I want you in particular to see this.” He struck a match and touched it to the bowl of his pipe. He puffed at it with the leisure of a man sitting in his own study, rather than overseeing the wreckage of a fellow man’s livelihood.

A cask was rolled out from the back by two of the women and uncorked in the middle of the room. The brandy spilled out onto the wooden planks of the floor, the smell so strong it made even Anthony choke. Where it didn’t pool it trickled down between the floorboards.

They made short work of it. When it was all over the chairs were in splinters, three illegal casks of spirits had been spilled out onto the floor, the barware was smashed, and the food stores ruined. The Ladies Society of Temperance left without a word, and the mayor’s rope-wielding associate with them.

With the last witness to the night’s calamity gone, the mayor walked a wide circle around the stunned proprietor and hapless guests, glass crunching under foot, careful not to step in the puddles of liquor that covered the floor.

“It’s a shame,” he said, and puffed on his pipe. “I took you for better, Harmon. You knew the law, and you knew you was breaking it. Can’t rightly blame the ladies for defending the town sensibilities. Still — “ He kicked a broken chair leg aside. “ — it’s a shame.”

He reached the front door and crouched down, pulling the matches from his pocket once again. Anthony’s mind clamored to make sense of what was happening — He’s the mayor, he can’t do this — as the man struck a match.

“Good night, gentlemen,” he said from the doorway, and held the match to brandy-soaked floor and stepped outside.

The spirits caught fire and the floor bloomed with bright blue flame, wending its way across the boards toward them. Anthony pushed past Harmon and ran for the kitchen. This seemed to jostle him from his stricken daze, and he quickly loaded Anthony’s arms with wet towels. The two of them did their best to smother the flames and keep it from reaching the walls.

“I’ve got it,” Mike called, carrying two full buckets, which he emptied onto the remaining flames near the front door. The three men stood side by side, watching the water drain away between the floorboards.

Something glinted on the floor beneath a settee across from the front desk. Of course, Anthony realized — the peculiar pin that belonged to the ghost girl. It must have been kicked clear across the room in the chaos.

He got on his hands and knees and reached for it. He could see it as clearly as if someone were shining a lantern on the space beneath the sofa, though where the light was coming from he couldn’t guess.

The light spread steadily outward — the otherworldly lantern lit first his hand, then the floor around it, and continued to grow. Anthony scrambled backward, trying to escape it, but the circle of light grew too rapidly, and as it enveloped him the room around him changed.

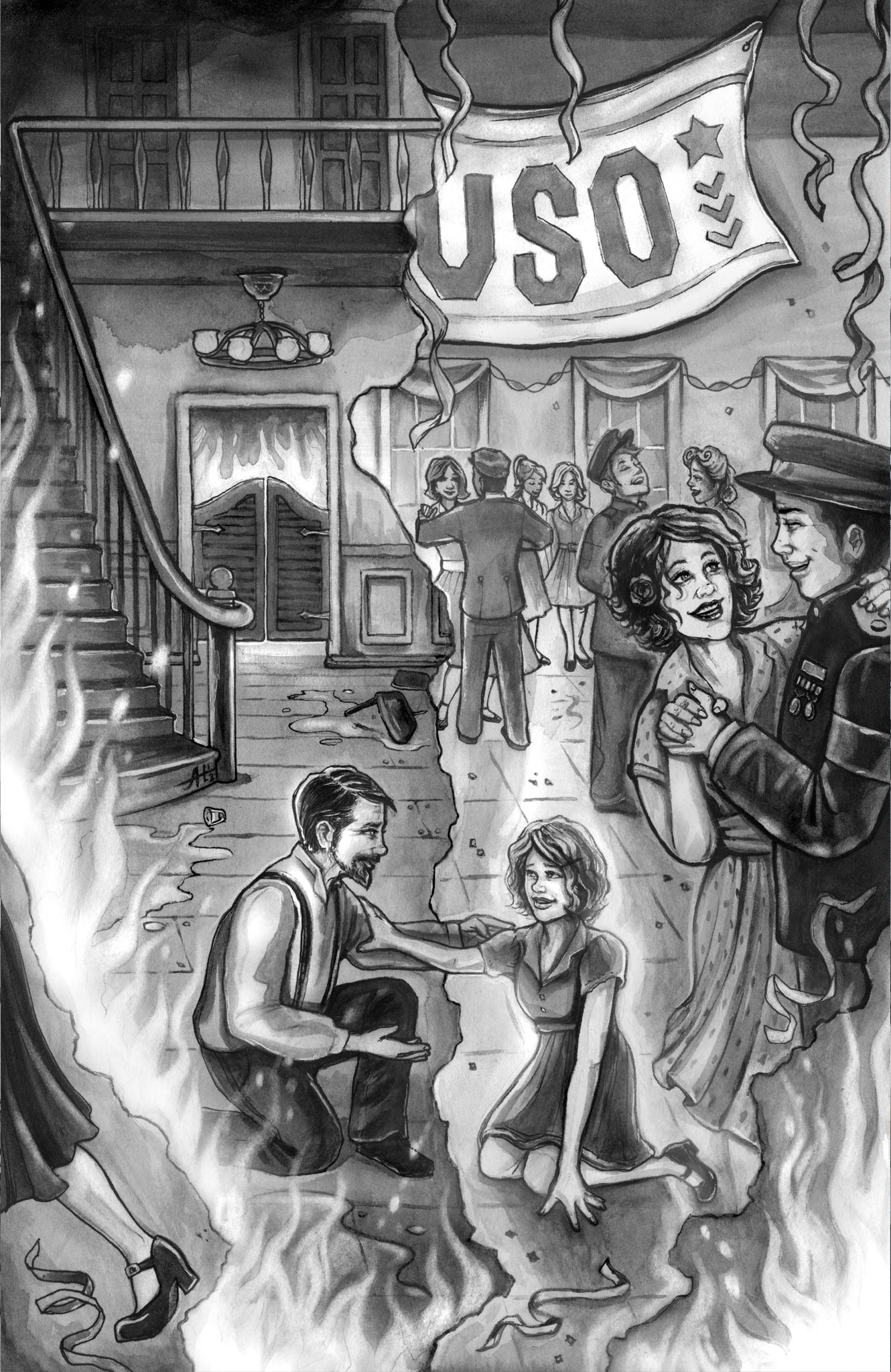

Music: loud, raucous, festive music, and laughter. He was on the floor in a sea of people, tapping their toes to the rhythm. Colorful, bare-legged girls danced with men all dressed alike, in khaki trousers and shirts. A banner hung from the back wall in patriotic red and blue, bearing only the meaningless initials “U.S.O.”

A few people looked at him oddly and moved away, but one young man looked him over and laughed.

“I didn’t know this was a costume party, chief. You came dressed as my grandpa!”

“Under the floor,” he could hear Mike calling from the shadows beyond the light, “the liquor’s still burning under the floor!”

And then the light reached Mike and Harmon, drawing them into this place, this strange vision — and with them came the fire.

The room erupted into chaos. The flames moved fast, the paper decorations that filled the room going up and creating embers that floated in the air, still burning and igniting whatever they came to rest on. People were screaming and pressing for the door, but it was blocked now by flames. Anthony couldn’t even see his companions over the heads of strangers. For a moment he was certain he would not survive this night.

And then, there she was. The ghost girl, her brow creased in fear, standing directly in front of him. For a moment it seemed she couldn’t even see him, as if she were looking through him or past him, at the flames that seemed to be all around now. He grabbed her by the shoulders.

“We’ve got to get you out of here.” He searched the room for an escape, pulling her along through the mass of terrified people to the far wall, away from the flames. He picked up a chair, and when she saw what he was doing, she grabbed another. “On three.” She nodded. “One…two…three!” They swung their chairs at the windows, breaking the glass. Anthony felt the cold air from outside rush in, and a sudden burst of heat at his back as the hungry flames found the fresh air. Anthony cleared the remaining broken shards from the window frame, and lacing his fingers together, offered the girl a stirrup to lift her up and through the window to safety.

“Get the fire brigade,” he told her.

“I will.”

He boosted her up, the muscles in his arms and chest straining, and then she found purchase and pulled herself up onto the window ledge.

“Wait, this is yours,” he said, and pulled the pin from his pocket. He held it up for her to see.

Relief was visible on her face as she reached for it —

— and was gone. The pin was in his hand. The wall before him now had no window, just the raw wood of the hotel. He sweated in the stifling heat and watched as the dance hall disappeared, collapsing from the perimeter inward, leaving only the burning hotel, and Mike and Harmon calling to him from where they had broken down the back door. He charged through the flames, the searing heat singing his face and his trousers alighting as he ran out the back and into the stable, where Mike tackled him to the ground and Harmon smothered his burning clothes under a horse blanket.

THEY SAT TOGETHER at Mike’s kitchen table in his tiny house in back of the foundry, the smell of smoke still in the air and on their clothes. Anthony passed a hand over his own face and brushed away the singed remains of his eyebrows. His leg was bandaged; the burn hurt, and he had nothing to ease the pain of it, until Mike produced a bottle and placed it at the center of the table with three glasses.

“We three must agree never to speak of what we saw,” Mike said as he poured.

“I’m not even sure what it was I did see,” Harmon said. “I know my business is destroyed. I’m not sure that any sideways vision, shared or not, really matters after that.” Harmon looked darkly into his glass. “Thank you both for trying. Who knows what would have happened had I been alone.”

Anthony lifted his glass to his lips and stopped.

“We all got out. I’m not sure that they all did,” he said.

“They weren’t real. They can’t have been,” Harmon said and poured another finger into his glass.

“I think they were. I think they’re real people, and our fire burned their dance hall down in another place. Or another time.”

Mike considered.

“The place did feel familiar. Like someone had taken the hotel and remade it into something else.”

“For a different purpose, in a different time,” Mike said, sipping his whisky thoughtfully. Anthony put his glass back down, the liquor untouched.

“And if things that happen in our time can jump through to theirs — people may have died tonight.”

“You’ve a peculiar mind, my friend.” Mike drained his glass and stood. “The two of you can stay here tonight. I’ll show you where to bed down.”

“I’m think I’ll stay up a while longer,” Anthony said.

“Suit yourself.” Mike and Harmon left him alone with his thoughts.

He thought again about the fire, the undecipherable letters “U.S.O.,” the eyes of the girl, so like his sister’s — no ghost at all, but a living girl. He sincerely hoped that she still lived, wherever — or whenever — she was.

He pulled the pin from his pocket and read the words again: Temperance Society for Historical Preservation. That’s what we need, he thought. To protect them from us, and maybe us from them. Preserving the history of every time, without interference from the past, or the future.

He poured the contents of his glass back in the bottle and stoppered it. The next steamer would have to leave without him. He would stay and see the mayor brought to justice; he would help rebuild the hotel. And he would find a way to keep the tragedy of the night from happening again.

He turned the pin over and noticed for the first time that there was fine engraving on the back, obscured by the hinged fastener. He unhooked the clasp and held it up to the lamp to catch the light.

The words were etched in a tiny, scrolled hand: Anthony Cardno, Founder.