Four Tons Too Late

by K. C. Alexander

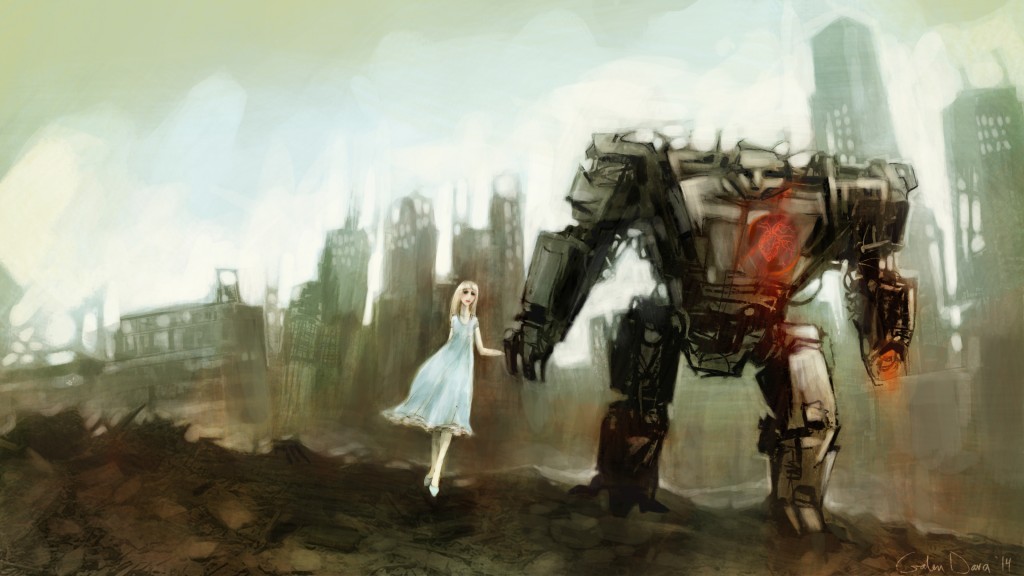

Illustrated by Galen Dara | Edited by Brian J. White

March 2014

Patient #8620-87

He wakes aching. He always wakes aching. Drugs don’t help. He kicked that habit a long time ago, before they’d take him into the program. Healthy bodies only, they said.

The dayshift nurse has already thrown the curtains. Daylight streams through the double-paned glass, warming the ambient temperature to 174 degrees. His internal therm is on the blink.

“Good morning, Frank,” the nurse says, his baritone cheerful. A male nurse. Ordinarily, Frank calls it the pussification of a man’s dignity, but he knows why he doesn’t get pretty female nurses anymore.

Things go wrong. Things get messy. He’d try to use the old tech in his hands, his legs, his head, and the wrong signals cross the wrong wires.

He’s a wreck, and he knows it.

The nurse is a shadow in Frank’s peripheral vision — whittled down to a tunnel. The pictures siphoning through the optics bolted into his brain come staggered, like a slideshow where the cables aren’t screwed in right.

“Breakfast is on,” the nurse calls from the kitchen. There’s nothing wrong with Frank’s ears.

The bed he’s on is a platform, a hard counter. No blankets, because the weave captures heat, and the last time Frank’s four-ton body overheated, he waited in silence — deaf, blind and dumb — for two days.

That’s when they’d put him here.

Frank doesn’t close his eyes. He doesn’t have eyes to close. He stares up at the gray ceiling and can’t remember what he’s waiting for.

Everything aches.

Officer Frank Mooney

3 Months

A hell of a storm rages. The real kind, with sharp winds howling in the filthy alleys between crowded apartments and where litter is snatched up off the dirty streets like bats out of neon hell. It rains like a son of a bitch, and Frank watches it slide down the window pane as his wife tells him that she wants out.

The door shuts behind her. The whisper of activity dies behind a reinforced steel panel. The cold hospital room doesn’t echo with raised voices — it would’ve been better if she’d yelled.

Frank doesn’t cry. He can’t. He doesn’t have tear ducts. They put in cybernetic optics with state-of-the-art enhancements, but they needed sockets to hold them. Frank’s face is stoic intensity — molded edges, chiseled planes. Tempered metal to encase the brain inside.

It’s supposed to stop a bullet.

It does shit for a breaking heart.

Patient #8620-87

Breakfast isn’t the word for it. The four-ton chassis, unlike the later models, doesn’t charge. Frank is forced to consume a gel-like substance that tastes like chewed-up cigarettes and copper-tinted lube, forcing it past a freakish amalgam of metal and flesh to drip like cold glue into his stomach.

Frank is lucky today. The pussified male nurse is a good kid. A steaming cup of stuff that reminds Frank of coffee waits on the pristine table, ready to wash down the metallic taste of the nutrient sludge.

He doesn’t always get coffee. The smell reminds him of memories now programmed into a chip. Long, hard days on the beat, casing petty thieves and drug peddlers from the front of a car whose bulletproofing warranty had tapped out years before. Swearing at the girls who didn’t know a cop from that hole between their legs, too caught up in the case at hand to bother with arresting them.

Peeing in a cup.

Heh. He doesn’t pee anymore.

Frank reaches for the steaming mug.

His fingers spasm. Metal joints lock, splay, and a charged jolt wrenches at his elbow. He clenches his jaw, gripping the edge of the table with his left hand as he tries to force control over the seizing right.

“Go, fingers,” he orders, but not too loud. He doesn’t want the nurse to come running. Doesn’t want the fuss, or the horror, or the blood.

He’s tired of blood.

The sun shimmers across the small breakfast nook as Frank forces his extremities to close, one by straining one, over the mug. Metal clinks. Joints lock.

He holds his breath as the tremors ease.

Rotors spin. Ceramic shatters into a fine dust between spasming digits as fluid sprays in a shit-colored arc across the table.

“God damn it!”

Officer Frank Mooney

1 Year, 7 Months

Storms herald change. They come a little less frequently now that the corporations have started to fine-tune the weather shield. It’s not perfect. This one sliced right through, a real doozy, forcing anyone with half a brain inside before the debris turns to shrapnel.

It’s a dark and stormy night, the kind of setting where a bad cop expects to find a desperate broad holding a gun with the business end cocked his way.

Frank finds a broad, but she’s not holding a gun. She’s got a sign. Anything for food.

What is she, eight? Nine?

Frank isn’t alone on this beat, but he ignores what the force calls his partner. It’s not a real word. Jenkins is a handler — half a cop, half a mechanic; a corporate shill. He’s been Frank’s handler since the first briefing on what it would mean to sell himself to the corporate labs. To get money for his wife’s — his ex-wife’s — treatments.

Jenkins, unwilling to step foot outside the one-man covered trike that protects his fragile flesh, wants out of this wind. He doesn’t slow.

Frank does.

He ignores Jenkins’s curse, harsh on the radio connecting them, as he veers off the programmed trajectory that is their beat. He slows to a halt beside the shivering little girl.

She’s got stringy hair and big, soulful brown eyes — the kind of eyes they paint on lifelike dolls to make them look real and sad and trusting. She doesn’t take a step back. She doesn’t cringe. Not like everyone else.

Four-ton chassis on mobility thrusters, one of half a dozen prototypes patrolling the streets, and people still can’t get past it.

“Get your scrapmetal back on course,” Jenkins snarls, but it’s a whine in Frank’s closed-circuit earpiece and he doesn’t care.

“You need to leave the area,” he tells her.

She stares at him. A little tired. A little resigned. A little too old for her terribly young face. The sign tilts.

“Do you have somewhere to go?” He can’t modulate his voice anymore. It’s metallic, like the robot his so-called partner accuses him of being. It comes out flat, tinny.

The wind shoves her hair into her face, a cobweb of greasy dishwater strands, and Frank clocks bruises on her wrists when she shoves the mess back out of her eyes. She doesn’t speak.

“Get off the street or I’m taking you in. Do you understand?”

She nods slowly as the wind tosses her hair like a wild corona. A greasy halo.

Frank turns away.

The faintest sensory input — a figment of feeling backlit by numbers scrolling past his left input device — halts him in place.

It isn’t a familiar sensation. His brain, fleshy and soft, slogs through numbers, calculations and theory. Searching for the memory. The description.

He can’t find it.

Frank turns.

A pale, dirty-streaked hand curls around the thick digit replacing his middle finger. It’s obscenely delicate against the black matte metal, ragged nails and all.

In the visual screen of his optics, the heads-up display tells him that she’s underweight. That her right arm’s been broken twice and her sign used to say something else before it was scratched off and appropriated.

“This is going down on the report,” Jenkins growls.

Frank rotates his free hand, bending it so far back that the palm detaches and a compartment slides open at the heel. A card pops out — one of those plastic ones, with a chipset in it. It takes him more than one try, but he manages to program the thin sheet. The address on the transparent plastic changes. “Get here,” he says.

She stares at him, her big brown eyes empty, but she lets him go to take the card.

He turns away again. “I was tossing a vagrant.”

“Screw you, Mooney.”

Jenkins doesn’t like Frank.

Frank wouldn’t mind snapping Jenkins’ neck. But that would turn Jenkins’ wife — Frank’s ex-wife — into a widow, and Frank doesn’t have it in him to do it.

One year and seven months after trading his body to the police force, Frank hasn’t figured out how to care.

“I’m back on course,” he says into the radio. There’s nothing in his voice. He’s a robot, after all. Just like they made him.

The middle digit on his left hand twitches.

Patient #8620-87

Frank isn’t allowed to have pictures. Nothing in here to remind of what’s out there. No memories. No nostalgia.

Nothing to make him test the borders they’ve put around his world.

The table is clean again, ceramic fragments swept into the trash bin and dropped down the garbage chute. He sits in the middle of his lonely suite, watching the byplay of sunlight and shadows dappling the far wall, and calls up a photo-perfect memory of a brown-eyed girl with flaxen hair.

It’s starting to go a little spotty.

Frank needs his recall fixed. They can’t do it. When the meat left over from his body started rejecting the nerve connectors, they tried for a while to stay on top of it, but then some snot-nosed_ wunderkind_ figured out what they’d done wrong first go-around.

Frank’s go-around.

They don’t make his parts anymore. That was always the risk. A few good years as they integrated the cyber division into the force and then so long, thanks for serving, here’s a gold watch.

Frank sits in his max-sec prison and contemplates hooking into the TV for some news.

The nurses don’t come for another few hours.

Detective Frank Mooney

4 Years, 8 Months

Things are looking up.

Statistics are in, and the corporations are pleased. The police force miraculously gains some funding, and Frank is promoted.

That means Jenkins is, too. The son of a bitch is going home with the promotion Frank always promised his wife he’d get.

His ex-wife.

“Thank you, cyber-detective,” operator says in his radio band. “You’re off the clock for six hours. Recharge.”

“Copy.” Frank doesn’t talk much. Nobody likes extended conversations with the cyber squad. Most don’t even know his name. Hey, buckethead, and Scrap squad tend to be the non-starters. “Out.”

He’s not alone. Frank doesn’t kid himself as he puts one blocky foot in front of the other and forces his four-ton chassis to the door of the complex reserved for cops. All cops, but mostly cops like him.

He’s got a basement deal, rent-free and reinforced to hold his weight. Part of the bargain. A pay-out with a whole lot of zeroes to fund his wife’s — his ex-wife’s — medical bills and a place to live.

Jenkins got the girl. Son of a bitch Jenkins.

The operator may be silent, but Frank knows he’s being monitored. Vitals, mostly. They tried to install cameras, but Frank shut them down.

He has a secret.

Frank lets himself in. The heads-up display flashes green, and his head turns on a servo a little less fine-tuned than it used to be. It whirrs.

There’s a shoe in his foyer. Small, narrow. Pink and white.

He aches as he clears the foyer, stepping over the shoe with exaggerated care. He’s ached a lot, the past few weeks. Sharp pains, sometimes. Dull throbbing in others.

He hasn’t reported it yet. So, he has two secrets.

“I’m back,” he says, in the same flat, mechanized voice he delivers everything in. He enters the kitchen — large enough to accommodate anyone else, but cramped for him — and tugs the refrigerator door open.

Muscles stretch under metal. Tighten.

Synapses crackle and the chassis seizes. Hinges pop and clatter to the floor. The whole damn door comes off in his armored hand.

The milk stashed on the nearly empty shelf topples sideways.

The broad waiting for him to come home steps into the space behind him. “I made cookies,” she says, reproachful. “The milk was expensive.”

The pool of white slips over the shelf’s edge and drips — splat, splat — to the tile.

Frank sets the refrigerator door down. “I’ll buy you more.”

She sidles around him, a twelve-year-old beauty with flaxen hair and soulful brown eyes. Small for her age, she looks almost as young as she did when he first found her on that dirty street. A little less starved, maybe.

“It’s okay,” she assures him, flashing a smile that pulls at the heart Frank doesn’t have. “We can eat cookies without it.”

He doesn’t point out that he doesn’t eat cookies anymore. It only upsets her. It took six months before she said a word. Now, he tries not to silence her.

She cleans up his kitchen — his mess — like it isn’t a problem. Like it’s the first time.

It isn’t.

Frank gets out of her way, knees cranking, body heaving into place like a metal avalanche. She’s humming as she drags a rag over the spill.

A real domestic type.

Her name, he learned, is Sabrina. She prefers Kate.

She pauses, looks over her shoulder — pink, his digital vision informs him, trimmed with white. Some kind of sporty sweatshirt she must have picked up when he sent her out with creds and a lifeless Whatever you need, kid. “Go pick a movie, okay?”

She’s gotten bossy. Informal adoption’s agreed with her. Even if the only thing keeping her under this roof is the promise of daily meals.

Frank leaves the kitchen.

Patient #8620-87

Frank hurts.

He always feels better in the morning than he does at mid-day. The hours tick by, and he sits quiet and still in his reinforced armchair. They don’t bother with padding. It can’t handle the weight.

The news is full of transhumanist hate speech. He can’t stomach more than an hour at a time, if even that. Hearing those talking heads bark about the transient nature of humanity and the threat cybertechnology brings to the species is enough to make his limbs twitch.

If he was still on the force, he’d go show those assholes a thing or two about transient humanity.

But he isn’t. They’d retired him, right? Took his badge, decommissioned his arsenal. Heh. Heh, heh. Said Gun on my desk, Mooney and he’d damn near dropped a nuke.

Nobody thought it was funny.

The last flawed prototype to get the boot.

Who wants him, now?

Frank sits in silence, hands draped on the arms of the chair, watching the shadows crawl over the wall with unblinking eyes.

Metal isn’t supposed to hurt. Didn’t somebody tell him that?

They lied.

Detective Frank Mooney

10 Years, 2 Months

“You aren’t my dad!” She stares at him across the living room, a sullen teenager with a spiky swatch of newly shorn hair tinted a color Frank thinks is purple. It could be black. Or dark red. The optics aren’t delivering.

Frank doesn’t know how to handle this.

If she was any other kid, he’d have her hauled in to the precinct and booked on drug charges faster than she could repeat all the many variations of the word fuck.

She knows a lot of them. Most didn’t come from him.

The servos in his neck creak as he lowers his head to the pink purse on the table in front of him. It was a gift. His first to her. He had to order it off the network because he’s encouraged to never go shopping.

She used to carry it everywhere. It vanished into her room one day, and she replaced it with other bags in a way Frank assumed was normal for girls.

Now, she’s filled it with drugs. The real gritty kind. Swish and canker, colordust and strych. The kind of stuff that kills kids like her.

She folds her arms in her clingy T-shirt and stares him down like he’ll be the first to blink.

He doesn’t blink. “I am not registered as your father,” he agrees, the speech patterns clicking faintly on every hard consonant.

“Damn right.” Her tone is snide. Her black-lined eyes look too small and angry. “So give it back. That’s a lot of money.”

“Do you take it?”

She says nothing.

“Do you sell it?”

She doesn’t incriminate herself.

“Silence noted,” he tells her, and flicks his left hand. It rotates backwards on rusty hinges, swaps out for a large, flat tube that unfolds even farther.

Sabrina blanches. “No, wait — “

The spurt of accelerant hisses as it hits the purse. The cheap plastic ripples.

“Stop!”

Frank does not. The clear liquid dampens the table.

She makes a move like she’ll leap for that little girl purse.

All it takes is a spark to light it on fire.

The inferno blossoms into a dark cloud, reaching for the ceiling and leaving a black smear in its wake. She throws herself to the floor, shrieking. “I hate you!”

That is normal.

The tube in his right arm clears the flap concealing it. Flame retardant sprays from his arm, but it doesn’t fall in a neat fan like it’s supposed to. The mechanism seizes. The congealed gel erupts from his outstretched arm. It splatters to the table in thick white gobbets, cracks the surface.

The air sizzles. He can’t hear anything over the horrific churn of empty tanks and sizzling flame. His elbow won’t bend to let him retract the tube, and the stuff churns out until there’s nothing left to spray, coat, break, or smear.

Frank looks dispassionately at the mess made in his own living room and doesn’t know the next step.

The drugs are gone.

So is the table, the sofa, the plaster on the ceiling and one wall, and the remaining veneer on his own arm.

Sabrina is gone, too.

Frank has to break the joints in his elbow to get it to bend again. It doesn’t hurt nearly as much as it should.

Leaving the useless limb hanging limply at his side, he cleans the mess.

When Jenkins shows up to address the alarming rise in Frank’s vitals, the air is thick with the chemical remains of burned strych.

Frank doesn’t explain.

Two weeks later, he is forcibly retired.

She doesn’t come back.

Patient #8620-87

The nurse doesn’t like it when Frank won’t eat. The staff has ways of forcing the issue. A short, sharp shock to his systems and his four-ton chassis lets him down.

Frank is force-fed the nutrient gel by grim men in white clothing, and he doesn’t get any of that coffee.

“Fucking trans,” one man mutters, nursing fingers Frank’s mouth clamped down on. He doesn’t have any teeth, but his metal lips are still rigid.

They leave Frank’s cell slapping each other on the back.

Neither look Frank in the face as the pins and needles of electric sensation once more ripple out to his limbs.

It hurts to be alive. He’s an investment. A thing. He belongs to the state.

He’ll die when they want him to.

Or once Frank’s mind has completely rotted away.

He doesn’t tell them about the pain.

It’s his only way out.

Fifteen minutes pass. He hears the mechanical lock snick open. There’s nothing wrong with his ears. The door hisses — a shot of compressed air from hallway to cell — and he can’t see who’s there.

He doesn’t ask. What does it matter? If it’s another one of those male nurses, he’ll just have to let Frank lay here until the four-ton chassis can leverage itself off the ground.

Frank is seized with an urge to laugh. He doesn’t. It will only come out disjointed and mechanized, like a computer failing to get the point of humor.

Footsteps click across the hard floor. “Look at you.”

A broad in a white lab coat stands over him. As far as disguises go, it could be better. The open coat doesn’t hide the skin-tight fabric of her crimson dress, or the mile-long legs wrapped in thigh-high black synth. The heels on those boots belong to a hooker, but the dark eyes looking down at him don’t come with an offer.

Her red mouth is turned halfway up, and halfway down. Strands of flaxen hair cling to her cheeks.

“Uncle Frank.”

He stares unblinkingly. “Visiting hours are over.” That’s the cop, somewhere in his chassis.

She bends, flashing a pale glimpse of thigh over the rim of her boots, and braces her elbows on her knees. She looks him in the face. Right in the narrow optics.

Frank doesn’t remember the last time anyone did that.

“Yeah, I know,” she tells him. She always was a know-it-all. “Can I stay?”

Whatever she’s been doing for the past six months, she’s been doing good for herself. He recognizes the subtle lure of creds in her get-up. Well, except for the stolen lab coat.

He doesn’t know what to say. His legs aren’t responding to commands yet. The whole thing needs a reboot, and Frank’s not sure he’s going to get one anytime soon.

She grins, but her face is mostly shadow in his spotty visual display. “I won’t stay long. And I’m sorry I’m late,” she tells him. “It took a while to get through security.”

“How did you know?”

“I have friends.” She touches his shoulder, but there’s nothing to tell Frank about it. No impression. No warmth. Just flesh on steel. Her nails are the same color as her lips. “How are you?”

He has no answer.

“Does it still hurt?”

“Yes,” he says, because this one is easy. Then, “They have cameras.”

“I know.” Her hand moves, but he can’t tell where. “I’ve got it handled. Do you want out, Uncle Frank?”

It’s a loaded question. He wants to ask her what she’s been doing since she left him, who she’s shacked up with. What her angle is.

He wants to ask her if she forgives him, ask her if she knows that he was no kind of father figure. No kind of protector for a girl like her.

He wants to know if she’ll leave again.

“Yes,” he says flatly.

There’s a glint of light — a flash, a spark — and she presses that hand over his optics. His already weak visual goes dark. “Do you trust me?”

Frank doesn’t know what that means.

“Yes,” he repeats.

“Then open your mouth.”

Frank does.

There’s a faint pinch at the roof of his mouth, where metal meets flesh. Then a lingering burn.

Her hand leaves his face.

Frank looks up into brown eyes, tendrils of soft gold draping her cheeks, and he wonders what it would be like to tuck that hair behind her delicate ear. See her smile again.

Maybe she can tell. “What are you thinking?”

“Can’t get out,” Frank begins. His mechanized voice falters.

She shakes her head, cupping his metal cheek. “It’s okay, Uncle Frank. You’ll be free soon.”

He wants to ask her what monster means to her.

He doesn’t.

“Kate.”

She smiles at the name. “Sleep,” she says softly. “I’ll stay.”

His optics flicker. The sensory input hitches, then flattens — as if he is in a long, narrow tunnel.

“Be happy,” he tries to say. It garbles.__

Her hands frame his face. She leans over him, presses a kiss to his forehead. “Don’t worry. I’m a tough broad.”

For one aching nanosecond, Frank imagines he can feel the warmth of that kiss. That he knows what the whisper of her flaxen hair feels like against his cheek. That he finally — finally — knows acceptance.

“Love you, Uncle Frank,” she whispers.

One by one, the chipset sensors in his septic brain short out. The chassis goes still.

Enough anesthetic, and even the four-ton anchor of his tech can’t keep him alive. Frank doesn’t hurt anymore. They can’t hurt him ever again.

It’s all Sabrina ever wanted.