Perspective

by Jake Kerr

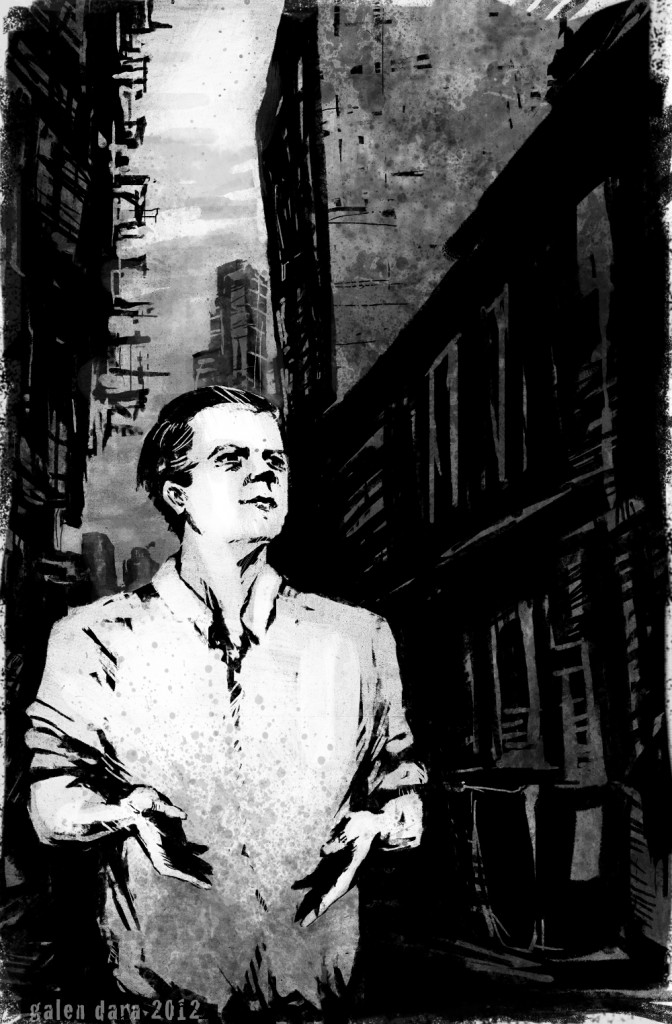

Illustrated by Galen Dara | Edited by Brian J. White

July 2012

The worst part about picking my son up from the police station was the walk to get there. I hadn’t been outside in years, but it was still the same — the drab gray of the smog-stained overcast sky, the decaying concrete, the stench of gasoline, urine, and who knew what else. But thanks to Jeffrey there was a new assault to my senses — black molecular paint permanently defacing an already wretched city.

With every step I could see his work — his “tags” as the police called them. They were all different, and there was no rhyme or reason as to what he would vandalize — the sides of buildings, street surfaces, retailer kiosks, even windows. The randomness made catching my son a difficult task for the police, but catch him they did, and now I had to walk these vile streets to bring him home.

I paid the bail, followed the directions to processing, and waited for my son. The policewoman there was polite and offered me a seat, but I stood. I wasn’t in the mood to relax, and Jeffrey needed to see how angry I was. So I waited, arms behind my back, staring at the door that led inside.

His head hung low as he walked out. He glanced up at me and then lowered his head again. “Hi, Pop,” he mumbled. I didn’t move. He walked over and added, in a whisper, “I’m really sorry.”

“You lied to me.” I grabbed his right hand and pulled it up between us. “These black stains aren’t paint, Jeffrey. That is your skin. It was the price to pay for your job, you said. ‘I’m painting ships with a new kind of paint,’ you said. You made the stains sound like a worthy sacrifice.” I tossed his hand down.

“Pop, please. Let’s talk about this at home.” He looked around the room, shifting from one foot to the other.

“Yes, we will discuss this at home.” I turned and walked out the door. He followed. I walked the streets again, Jeffrey shuffling behind me. I focused on the concrete at my feet, unable to bear looking at his work. My hands were clenched tight enough to turn my knuckles white, so I shoved them in my pockets.

I closed the door and set all the locks. I couldn’t remember the last time I had left the apartment for the drab world outside, and I did not intend to do it again. Jeffrey followed me in and stood near the door as I sat in my media chair. The distance felt greater than the span of a room. At least he was quiet and respectful. I sighed.

“The lies are what bother me the most, Jeffrey.”

He stiffened. “I never lied.”

I frowned and raised my voice. “You never lied? You said you were working at the shipyards!”

“I did work there. I painted ships.”

“Did you, now? Or were you defacing them in the middle of the night?” I pounded my hand on the arm of the chair. “I was sad, but I was still proud of you, Jeffrey. All those art lessons. All those awards. That you couldn’t make a living with your art broke me up inside. But to see you finally turn your art into industry, even if it required your hands to be stained that horrible coal black. That was a price I could at least understand. You were doing something meaningful.”

As I shook my head, he interjected, “I am doing something meaningful, Pop.” His voice rose. “You just don’t understand!”

“Painting permanent black marks across the city is not meaningful. This ‘tagging’ that the police told me about. It’s a mark of pride, they said. A way for gangs and others to know that this is your city.” I closed my eyes and lowered my head. “I thought I had raised you better.”

“Pop, I wish I could explain, but I’m not done. When I am, you will understand.” He looked so earnest and so sad. I stared at him, and he lowered his head. Despite his hope, I knew I would never understand. How could I? He was marching off to scar the city again, and he expected me to just accept it. I couldn’t.

I stood up. “Not done? You have shamed me, Jeffrey. Made me leave my home. Lied to me. And you are not done?” I walked over and waved a finger in his face. I considered striking him. I had never done so, and perhaps that was my mistake. Perhaps I was weak, raising him alone and not wanting to bring him any more sadness and pain than he had already experienced through the death of his mother.

A tear slid down his cheek, and I lowered my hand. “You don’t understand, Pop.” He said it in a whisper, then turned and strode down the hall to his room. I sat back down and dropped my head into my hand. I wasn’t sure where I went wrong.

Other than a few curt questions and answers, we didn’t talk during breakfast the next morning. Jeffrey seemed distracted and troubled, and I didn’t want to intrude. I felt that he had finally come to his senses and was working up the courage to apologize to me and present some kind of plan for turning his life around. So I gave him his space.

I was shocked, then, when he grabbed his keys and walked toward the front door. “Where are you going?” I asked, none too gently.

“I have work to do, Pop. Please let me be.”

I hurried over to him and grabbed his arm. “You are not leaving this apartment.” I held tight. “What work could you possibly have to do? Tagging some neighborhood dogs? Maybe getting arrested again, so I have to leave my home and walk these cursed streets?”

He pulled his arm free and turned to face me. “That’s the problem, Pop. You never leave the apartment. Ever since mom was hit by the car, all you’ve done is sit in your chair and look at old photos and read old books.” He was animated, and his desperate tone didn’t anger me so much as make me sad. “I’ve begged you to come with me, somewhere, anywhere. Hell, Pop, you won’t even go on the balcony.”

I dropped my arm back down to my side. I wanted to ask what this had to do with his delinquency. I wanted to ask why he was attacking me when he was the criminal, but he looked so concerned for me that I felt I had to respond. “There is nothing outside for me. You’ve seen how the city has changed. There is no beauty left. It’s all gray and drab. Why would I voluntarily walk through such a depressing world? Why would you want that?”

He shook his head. “I get it, Pop — clouds, concrete, smog. You’ve said the same things for years, but there is beauty in the city.” He walked to the door, opened it, and then turned back to me. “Mom saw it.” He closed the door behind him. I stood for a long while, unmoving, staring at the door. At some point I went to bed.

A day later I had unlocked the front door and considered going out to look for him, but I never opened it. It would have been hopeless searching amongst that sprawling compost heap.

I phoned the police on the second day and asked for help, but they already knew that Jeffrey was wandering the city. They called me back the next day. There was no bail this time.

I asked what happened, and the policeman curtly told me to just check the news. I did. Jeffrey had painted non-stop since he left our apartment, in a manic attempt to spread his tags across the city. The judge who originally allowed him bail was being pilloried by the press for releasing the infamous “Nanotagger” the first time. It wouldn’t happen again.

I hadn’t watched or read the news, so I didn’t realize that Jeffrey had generated worldwide attention. To some he was the new Banksy. To others he was a new breed of criminal, permanently vandalizing the city. To me, he was my son, my misguided, damaged, motherless son.

I ignored Jeffrey’s calls. His messages were plaintive requests for me to come talk to him, but I just couldn’t do it. What was there left to discuss? His final message was a request for me to attend his sentencing. He had something important to say, and this would be his last opportunity to say it to me in person. I was sure he assumed I wouldn’t leave the apartment to visit him in prison, and he was probably right. So when he asked if I would come as one last show of fatherly love before he was gone, I knew I would.

I made the walk to the Laura Tejeda Courthouse. It was the big one halfway across town, which only made the walk worse. Even the bright windows of the glass buildings did little more than reflect concrete and smog. High up one building I noticed the black paint of Jeffrey’s hand. It was little more than an oval. I tried to see it as art, but could not. It was just graffiti. Ugly black graffiti.

The press was everywhere. Microphones were thrust in my face, holo-cameras with bright lights aimed at me. I ignored the shouts of “Mr. Chapman!” or the rudely personal “Bill, Bill Chapman!” and shoved the microphones aside. People stared at me as I walked down the courtroom aisle, but I paid them no mind and sat near my son. He saw me and smiled. He wiped his eyes with a thumb and forefinger and then looked at me again. He held up his forefinger, as if telling me to wait.

It didn’t take long. Jeffrey pled guilty, and that was that. The judge asked if Jeffrey had anything to say. He stood up. His hands were shaking as he turned and faced the people packed in the courtroom. “I want to apologize to the citizens, officials, and merchants of the city.” His voice trembled and was almost a whisper. I doubt many heard him. But I did. “I cannot explain why I did what I did, but I do accept responsibility for my actions.”

Jeffrey then turned to me and started crying. “Pop, I have so much I want to say to you about what I did, but I’m afraid you won’t listen. So, I’ll just ask you for a favor, one simple favor.” I lowered my head. I didn’t know what he wanted, but I was sure I couldn’t help him. The thought of being powerless to help him brought tears to my own eyes. “Pop, all I ask is that you go out to the balcony of our apartment, look around the city, and think of me.” He wiped his eyes with his sleeve. “It may not be a lot, but it would mean a lot to me.”

He then turned to the judge and stood quietly as he was sentenced to ten years in prison for maliciously defacing public and private property. The fact that he used molecular paint was ultimately the real problem. He stole it from the shipyard, and stealing nanotechnology — even paint — was a felony.

I walked home, and the city was even more depressing, if that was possible. I sat down in my chair and pulled out the computer. I spent the rest of the afternoon looking at baby photos of Jeffrey playing with his mother. I cried.

I went to bed without stepping onto the balcony. I knew what Jeffrey was trying to do. I knew that he thought I was agoraphobic and that having me at least step on the balcony would be a step to freeing me from our — my — apartment. But Jeffrey just didn’t understand. I walked to the police station. I walked to the big courthouse. I could leave whenever I wanted. I just didn’t want to. The city and world were just too ugly.

The next morning I checked the news. It was the same story. Jeffrey was an anti-establishment hero. Jeffrey was a symbol of the cancer eating away at the city. I closed the computer window. The last thing I saw was a holo-image of Jeffrey standing in the courtroom.

I looked through the dining room. The curtains to the balcony were closed. I may have failed him as a father, but I could at least do this one last thing for him. It was silly and stupid, but it meant something to my son, so I did it. I walked over, opened the curtains, and looked out into a sky of gray clouds and smog. I shook my head and opened the glass sliding door.

I walked outside and over to the railing. I looked down at the city my son had used as his canvas. The view staggered me, and I grabbed the railing for support. I looked across concrete sidewalks, streets, glass, buildings, and kiosks — all of them permanently marked with black brush strokes. Each mark was a small part of a majestic, gorgeous whole — a painting of my wife as big as the city itself.

I held out my hand into the air, reaching through the distance to touch a piece of art that was untouchable. My wife’s eyes, the curve of her cheek, even the mischief in her smile. It was all there.

I couldn’t believe the scale of Jeffrey’s accomplishment. Each small piece of black paint was part of a whole that could only be perceived from this balcony, this exact spot. She looked back at me — the city, my wife. She was beautiful.

Ten years was too long to wait to hug your son, but sometimes you don’t have a choice. I wiped my eyes and moved my chair out to the balcony.