Rhapsody in Blue Shift

by Stephen Blackmoore

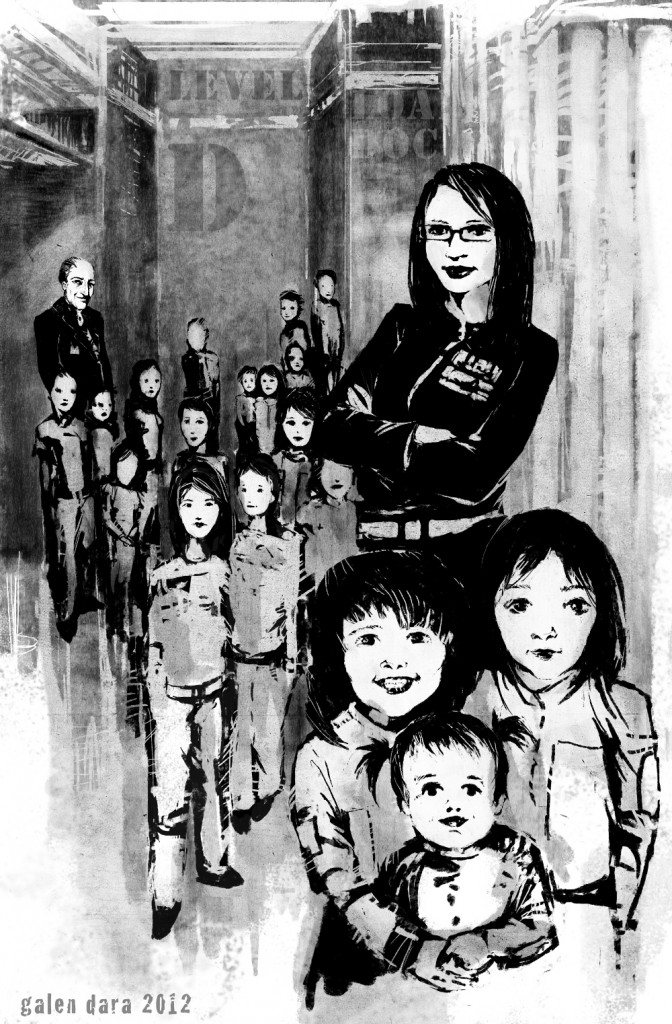

Illustrated by Galen Dara | Edited by Brian J. White

July 2012

When I met George Gershwin I was cleaning up D Deck. The gravitational retractors had gone offline, sending clothing, magazines, a thousand odds and ends into the air. When they finally came back down it was my job to clean up the mess.

D was the refugee barracks where the captain of the Don Pasquale kept the “unscheduled” passengers. Normally we’d pick up passengers from planets along one of the main tourist routes, heading out of Phalanx or l’Avignon, under contract from one of the cruise lines.

Until the war changed everything. Now we carried desperate mothers, frightened children. We got them to neutral ports, but there were just so many of them.

We had to convert D just to lodge them. Half of C became a hospital ward. There was talk of tripling up bunks so we could expand further. We were drowning in a sea of refugees, the tide rising even as we bailed.

We cleared the deck when the gravity shut down to keep folk from being hurt. I pulled three mewling toddlers off the ceiling. That and my cleanup duty as a Janitor 3rd Grade would net me good overtime.

That’s why I was in the maintenance halls of D Deck, all alone, when George Gershwin walked in.

I didn’t know it was him, of course. I just saw a middle-aged man, with short dark hair thinning atop a long, hangdog face. He was wearing a suit and tie, something I hadn’t seen since I was a kid. My great grandfather had been a historian, and we’d watch old vids from a couple centuries past together. People dressed like that in those days.

But no one would ever do it aboard a starship. Too many things that can snag a finger or a foot, let alone something as ridiculous as a tie.

I stopped my vacuuming and looked up at him. His face was long and weathered. Though he smiled, there was sadness in eyes set small beneath thick bushy brows. Still, he seemed happy to see me. Usually the refugees would scowl when I came down to fix a clogged toilet, a busted shower. I was one of the hated elite. I was Crew.

“Mornin’, Sid,” he said, stepping through the iris valve door behind me. His voice was thick with a hint of Old Brooklyn in it.

“Morning. This area’s off limits until cleanup’s done, sir,” I said, ignoring that he seemed to know my first name. “You’ll have to go up to C. Only another hour or so.”

“Why would I want to do that? I came all this way just to talk to you. I can’t very well do that sittin’ up on some hospital couch with a popsicle stick in my mouth, now can I?”

“Me, sir?” I’d gotten into the habit of calling everyone who wasn’t part of the crew “sir.” Be polite to everyone, my momma taught me, and you can’t go wrong.

“Got wax in yer ears?” he asked, still smiling. “Sid Cooper, right? Good Ol’ Sid. Janitor 3rd Grade. Gonna be a hero some day, that Sid Cooper. That’s the talk I hear.”

“I’m sorry, sir, but you’ve got the wrong guy. I clean toilets and vacuum trash.”

He gave me his hand to shake. My momma always told me to never trust a man with a weak handshake. His handshake was strong. Momma never told me whether to trust that kind of man.

“Name’s George, Sid. George Gershwin. Tin Pan Alley man from way back.”

“Pleased to meet you, Mr. Gershwin. If you don’t mind, though, you really need to be up on C.”

“Oh, I know. Just wanted to pop in and say hello. Sort of by way of introduction. You listen to music?”

“Some, sir.” Mr. Gershwin made a face.

“Some. Huh. Listen, can you do me a favor? Can you hang around B Deck near the communication relays for the environmental modules in say,” he glanced at a small, rectangular watch on his wrist, “half an hour?”

“I suppose so,” I said. Another ten minutes and I’d be finished.

“Thanks a million. I’ll go head on up to — “ he gave me a knowing wink as if I was in on a joke, “ — C Deck.” He turned to leave and stopped.

“Oh, and one other thing, Sid, if you wouldn’t mind.”

“Yes, sir?”

“Bring an 18mm optical pump with a double tier connection.” I looked at him, confused. “Might be a good idea.” He winked at me again and stepped out of the room.

“Hey, Sid.” I turned back to see Wally, trundling into the room with that goofy walk of his. “You almost done?”

“Almost,” I said. “Mr. Gershwin came in, and I was talking to him for a minute.”

“Gershwin?” Wally asked.

“I think he was one of the refugees,” I said. “Dark-haired guy. Weird looking clothes? Must’ve walked right past you.” Wally frowned, his whole face drooping. He look back. Nothing but a long stretch of sectioned halls behind him.

“Didn’t see nobody.”

My momma told me to never trust a man who uses a double negative. “Then you weren’t paying attention,” I said. “He was right here.”

His frown deepened, which on Wally was a heck of a sight, believe me.

I pointed to the headphones hanging around his neck. “Probably listening to your music. Got distracted.”

“Yeah. Must’ve been it. You done, yet?”

“Almost.” I turned back to my work and paused. “Wally, you know where I can lay my hands on an 18mm optical pump with a double tier connection?”

“Dunno. Maintenance on B? What do you need it for?”

“No idea. Just know I’m supposed to get one.”

Twenty minutes later I had the pump. It was a small black box with a connection on each end and a set of interlocking rings surrounding them. It was as plain a piece of machinery as they came.

They were scattered throughout the Don Pasquale like rats in a ghetto. Every time I opened up a panel to clean some gunk lodged in between the vent piping, there they were. They were part of the communication system passing signals back and forth through the ship. Without them the ship couldn’t function.

I made my way to B Deck, near Environmental. The relays that Mr. Gershwin was talking about were between Engineering and Water Reclamation.

I wasn’t sure about Mr. Gershwin. He was about the oddest thing I’d seen on board, and with a hundred passengers per trip and three times that in refugees, I’d seen plenty.

Probably should have reported him to my shift supervisor, but I didn’t know where Leo was, and I didn’t have time.

If Mr. Gershwin had done something on B that I could have stopped, I’d feel awful. Not to mention, probably dead. The environmental modules control the air mixture, pressure, lighting, the works.

This section of B was pretty quiet. My shift, Blue, had ended a few hours ago, and Red shift was already on C Deck. I’d only been up because of the gravitational retractors.

So when the alarms went off and the intercoms started squealing, I was the only one there.

I could hear panicked calls from Engineering for maintenance assistance, and saw blue smoke coming from the panel in front of me.

They were already losing pressure in sections of C Deck.

I pulled off the panel, put out the cable-chewing flames with one of the extinguishers seeded throughout the ship.

The primary and secondary couplings were toast. It was their optical pumps. I’d seen it before. There was suddenly too much traffic for the relay to handle, and the optical pump had routed over to the secondary.

But the load was too heavy. So much so that it burned itself out. With the primary pump gone the remaining traffic had flooded the second, which tried to do the same thing as the first. And now it too had failed.

The tertiary pump was beginning to smolder.

These were 9mm pumps. The quantum drive computers that shove the Don Pasquale through folded space use 18mm pumps. If there’s so much traffic that it can’t be handled by an 18mm pump then you’ve got bigger problems.

I pulled the charred primary pump from its housing and dropped its smoking remains on the floor. Blowing on my burnt fingers, I connected the larger pump with my other hand.

Just in time, too. The tertiary pump popped, and the traffic re-routed back to the beginning, where it found a nice, fat pipe to run through.

The alarms went silent. Reports started coming in of pressure going back to normal. A confused maintenance crew arrived just as the all clear sign was called. They had a security detachment with them.

That’s when I went to the brig.

“Who told you to go up there, again?” Captain Martha Fischer asked. She was a small woman with a high forehead. Kept her graying hair short, made a habit of meeting with everyone on the crew at some point. I liked her.

“George Gershwin, sir.” Captain Fischer and First Mate Weiss had been exchanging looks for most of the conversation. “I think he’s one of the refugees.”

“Do you listen to music much, Sid?” Captain Fischer asked. We were in her office, the Captain, the First Mate, and my shift supervisor, Leo.

“That’s exactly what Mr. Gershwin asked me.”

“Sid,” the First Mate said, “how did you know how to fix the optical pumps?”

“I clean there every day. I had to read the manuals before getting onto Blue shift.” I looked at Leo, who was sitting stiff in his chair and sweating.

“Yes,” Leo said. “We don’t want the janitorial staff damaging sensitive equipment, so we give them rudimentary training.” He hooked a finger beneath the collar of his uniform to let a little air in. “Sid’s particularly good at it,” he added.

“Did Mr. Gershwin do anything?” I asked. “I hope not. Seemed a nice guy. Had a strong handshake.”

“No,” First Mate Weiss said, “it doesn’t seem anyone actually did anything. The system’s showing some wear. It’s a miracle they didn’t give out sooner.”

“I’m troubled by these reports of an unlisted passenger predicting crucial equipment failure on my ship, Sid,” the Captain said. “I’m going to release you, but if you see Mr. Gershwin again, report him to security.”

“Yes, ma’am,” I said, and that was that.

I didn’t see Mr. Gershwin again for a few more days. When he showed, he scared me half out of my wits.

“Hey there, Sid,” he whispered in my ear. I jerked awake and hit my head on the underside of the bunk above me.

“Heck, Mr. Gershwin,” I swore, rubbing a swelling lump on my scalp.

“Sorry, kid,” he said. “It’s Showtime.”

“I got into trouble because of you. They were going to lock me up. My momma said to never trust a man who gets you into trouble. I’m supposed to report you.”

“Your mother is a wise and wonderful woman, Sid, and sends her regards. Now get a move on.” I pulled myself out of bed, grabbed my coveralls.

“Not much time, Sid,” he said.

“Not much time for what, Mr. Gershwin?”

“The riots that are breaking out on D.” I stopped as I was zippering up my front.

“Riots?”

“Would I lie to you?”

“I don’t know. You haven’t told me why you’re here.”

His face cracked into a grin. “But that’s not lyin’. That’s just not tellin’ ya everything.”

“It sounds an awful lot like lying to me, Mr. Gershwin.”

“As we head down I’ll fill ya in. That work?”

“I suppose. But I really need to report you, Mr. Gershwin.” He clapped me on the shoulder as I stepped into my boots.

“I understand, Sid. Duty calls. But, really, what’s more important? Preventing a riot, or callin’ Leo?”

“I was in the brig because of you.”

“Did you know that there are almost a hundred children down on D? Poor kids. Orphans mostly. Sad.”

“You’re trying to get me into trouble again, aren’t you?”

“Trouble? My word, Sid. Why would I want to do that?” he said. “I just want to help those poor orphans. Did I mention there’s almost a hundred of ‘em? They could get hurt in a riot. Especially on board a ship where there’s nowhere to go. But if ya need to report me instead of helpin’, I understand. Duty.”

“Yeah,” I said. “Duty.” Mr. Gershwin was walking ahead of me as he spoke. I didn’t want to lose him, so I let him lead the way.

Something wasn’t right. “Hey,” I said, finding a hole in his story. “Why aren’t we hearing alarms?”

“It’s not a riot, yet,”

“Then what makes you think there’s going to be one?” He rounded a corner and stepped in front of the open double doors to Food Storage 87.

“That,” he said, and pointed to a large pile of crates stacked on a cargo lifter. Food delivery wasn’t my area. I was a Janitor 3rd Grade. But I knew my shift and who was around before and after. The provisions in FS-87 were for refugees on D. There was a full day’s worth of food here.

“They got nothing to eat?” I asked.

“Not all day. Been hollerin’ since last night. Bureaucratic snafu,” he laid an index finger against his nose and winked.

“But there are kids down there,” I said.

“Orphans even,” Mr. Gershwin added.

“This isn’t right.”

“So, what are you gonna do about it?”

They were going to riot if they didn’t get food. I squared my shoulders and hauled myself into the seat of the cargo lifter. It was like the tractors back home on the farm, all yellow metal and industrial rubber. Didn’t take me long to get it moving.

Mr. Gershwin was next to me as I backed the lifter into the dispensary elevator. As the doors shut and we started our slow descent, Mr. Gershwin started to hum.

“That’s a nice tune.”

“Thanks, Sid. One of mine. I’m a songwriter by trade.”

“But you said you were a Tin Pan Alley man from way back,” I said.

He laughed. “You don’t forget anything, do you? Yeah, I’m a Tin Pan Alley man. Means on my good days I’m a songwriter, on my bad days I’m a hack.”

“Can I ask you a question, Mr. Gershwin?”

“Shoot, Sid.”

“Who are you?”

“Well, that’s a tough one,” he said. “I’m a friend, and I’ve got a duty, too.”

“That’s no kind of answer,” I said. “You’re not one of the refugees. You’re dressed wrong, too.”

“You listen to music much, Sid?”

“You asked me that already.”

“Finish this up and when you get back to your bunk there’ll be a surprise for ya,” he said. “Can’t answer much more than that, Sid. Sorry.”

I didn’t like it, but my momma always told me that if someone doesn’t want to talk there’s no sense in trying to make him.

“Okay, Mr. Gershwin. But after this I need to report you.”

“Understood, Sid.”

The cargo elevator ground to a jarring halt. It paused, and with a metallic grind the doors opened onto chaos.

Refugees had torn huge holes through the cheap, plastic walls of the dispensary using whatever they could get their hands on. They were trying to get the food they believed was inside. I could see desperate people, angry faces through the holes. Some children, wide-eyed and hungry. A day on an empty stomach on a ship where the gravity goes off and the air pressure goes up and down was enough to make anyone crazy.

They saw me and the cargo lifter, and stopped. The moment hung in the air. Knowing that soon enough one of us would have to move, I decided it’d be better be me.

I eased the lifter forward. The dispensary was completely automated, provided it was supplied with food. There was more than enough room for me to spin the lifter around and get it in place for the loading arms to engage and restock itself.

“It’s okay,” I yelled. I flailed my arms to be understood. The loading arms behind me hummed. I raised my voice and spoke more slowly. “Don’t riot, please. You don’t… need… to… riot.” One of the children watching the loading process looked at me.

“We figured that out, mister.”

One of the men looked at me through the hole.

“I guess… we should line up for lunch then?”

“That would be a good idea, sir,” I said. “The autoloader will be finished soon and then there will be hot food for everyone. Could you organize something so that the little ones can get fed first?” He nodded and began barking out orders. I left him to it and turned back to Mr. Gershwin. He was gone.

But a security team was standing in his place.

“Let me guess,” Captain Fischer said. “George Gershwin, again?”

“Yes, sir. He says he’s a songwriter from Tin Pan Alley, but sometimes he’s a hack.”

“Ya don’t say.”

I was nervous. I didn’t know what I was saying. The security cameras had seen me walking into FS-87 and driving the cargo lifter down to D Deck. Alone.

We were in Captain Fischer’s office, just her, First Mate Weiss, and myself. They hadn’t bothered to call Leo this time.

“What is this, Captain?” First Mate Weiss said. He was exasperated.

“Patience, Randall,” Captain Fischer said, not looking at him. “I’m sure Sid will tell us everything.” First Mate Weiss glared at the Captain behind her back, but Captain Fischer just kept looking into my eyes and smiling. “You think you could go over it again, Sid?”

I did. I told her everything. I’ve got a good memory. Captain Fischer kept smiling, and nodding at the right places. I liked Captain Fischer.

“I can’t believe we’re listening to this,” First Mate Weiss said. Captain Fischer ignored him.

“Had you ever heard of George Gershwin before that time when the gravity went?” Captain Fischer asked.

“No, ma’am.”

“Didn’t think so. You can go, Sid.” She stood and patted me on the shoulder.

“Should I report seeing Mr. Gershwin again, if I see him?”

“Oh, definitely, Sid. Definitely.”

When I got back to my bunk I was alone. Someone had left a pile of data slivers. “Porgy and Bess,” “An American In Paris,” “Piano Concerto In F.” And a small, handwritten note.

“Have a listen. –G”

I picked up a sliver and slotted it into my music headset. The music rose up from the silence, filling my head with liquid gold. Piano keys pounded out tones, half steps, danced around melodies.

I lay there the rest of my off time listening to the singing, the melodies, the music. I savored every note, like it was the finest wine, let images dance in my head like they were sugar plum fairies at Christmas.

It was the most beautiful music I’d ever heard.

Mr. Gershwin caught me in the mess hall a few days later. The last of Green shift had left to start their rounds and no one from Red had come in. For a few minutes, at least, I was alone.

“Evenin’, Sid,” said Mr. Gershwin, standing at my elbow.

“Evening, Mr. Gershwin. How are you today?”

“I’m well,” he said with a twinkle in his eye. I hadn’t noticed the twinkle before. Maybe it was because I hadn’t known he could write such wonderful music.

“Are you really George Gershwin?” I asked.

“Yes, Sid. I’m really George Gershwin.”

“You said my momma sends her regards. You seen her?”

“Oh, yeah. Karina Cooper. She’s a pistol! Mean poker player, too. Word to the wise, never try drawin’ to an inside straight.” Yeah, that sounded like momma, all right, God rest her soul.

“You’ve been awful helpful, even if you’ve gotten me into trouble. Why? And why you? Why not your brother Ira, or Irving Berlin?”

Mr. Gershwin laughed. “You’ve been doing your homework, haven’t you? We’re all just regular folk, Sid. Doesn’t matter if you invented fire, made a million on the horses, or ruled a country. We’re all just people. That’s why I’m tryin’ to be helpful. As to why it’s me here and not somebody else?” He gave me that broad wink of his. “Word to the wise,” he repeated, “never try drawin’ to an inside straight.” He laughed. I didn’t get it.

“Thanks for giving me that music, Mr. Gershwin,” I said, changing the subject.

“Thought you might like it. Now, why don’t you finish up that soup before it gets cold. We’ve got work to do.”

“I know, Mr. Gershwin,” I said. “You only show up when there’s work to do.”

“Don’t sound so glum. This is good work.”

“If you say so, sir. But I bet I’m going to get into trouble. Again.”

The grav-ball courts were always their quietest at this hour. Mr. Gershwin took me to the observation lounge. He motioned me to duck. I squatted behind a chair and looked down into the court.

“See that?” he asked.

“It’s First Mate Weiss,” I said.

“And what’s he doing?”

“He’s handing something to a man. Looks like one of the refugees. What is that?”

“It’s a bomb, Sid.”

“A bomb?!”

“Whoa! Hold your horses. It’s okay. Neither of them are what you’d call ‘good people,’ Sid. Weiss is trying to make some money on the side. The other guy is a terrorist. He wants to blow a big hole in the ship on D Deck. It won’t hurt anyone, though. Except for a lot of the refugees. Did I mention that a lot of the kids are orphans?”

“Yes, sir,” I said. I had to do something. What did Mr. Gershwin want me to do? I asked him.

“Oh, you’ve done plenty, Sid,” he said, grinning. “Just one more thing. Can you repeat after me?” I nodded. “Weiss’ journal and list of accounts is in his personal safe. The combination is 27, 43, 9, 18, 2.” I repeated his words.

The refugee with the bomb was handing a steel case to First Mate Weiss.

“I’ve got to do something, Mr. Gershwin,” I said and turned. He was gone. In his place was a security team.

But this time they weren’t there for me.

This time First Mate Weiss went to the brig. He was the one who’d kept the food from going to D. He’d installed faulty optical pumps into the communication relays and shut down the gravitational retractors, too. My momma used to tell me that we all get what we deserve. I hoped so.

Captain Fischer called me a hero. She apologized for putting that micro-transmitter on my uniform. She said it was because she wanted to keep track of me in case I saw Mr. Gershwin again. I’m not sure she really believed that Mr. Gershwin was there. But if it hadn’t been for the transmitter she wouldn’t have heard me talking about the bomb or First Mate Weiss’ safe.

I only saw Mr. Gershwin one more time. I was cleaning up on D where the refugees had brought animals aboard. I always hated that job.

“Hoo!” a voice cried from the door behind me. “This place reeks like the Bronx in summer.” Mr. Gershwin stood there squinting and waving a hand in front of his nose.

“Good morning, Mr. Gershwin,” I said.

“Mornin’, Sid.”

“Is there more work to do?” I asked.

“I’m here to help you this time. You’ve been a sport. Anything I can do for ya?”

“Captain Fischer doesn’t believe me.”

“Can you blame her?” he asked. “It’s not like she’s seen or heard me. You want her convinced?” I nodded.

“Consider her convinced,” he said winking at me. He didn’t even say goodbye, just faded away with that grin of his.

And that’s when the music started playing. All over the ship.