The Unusual Customer

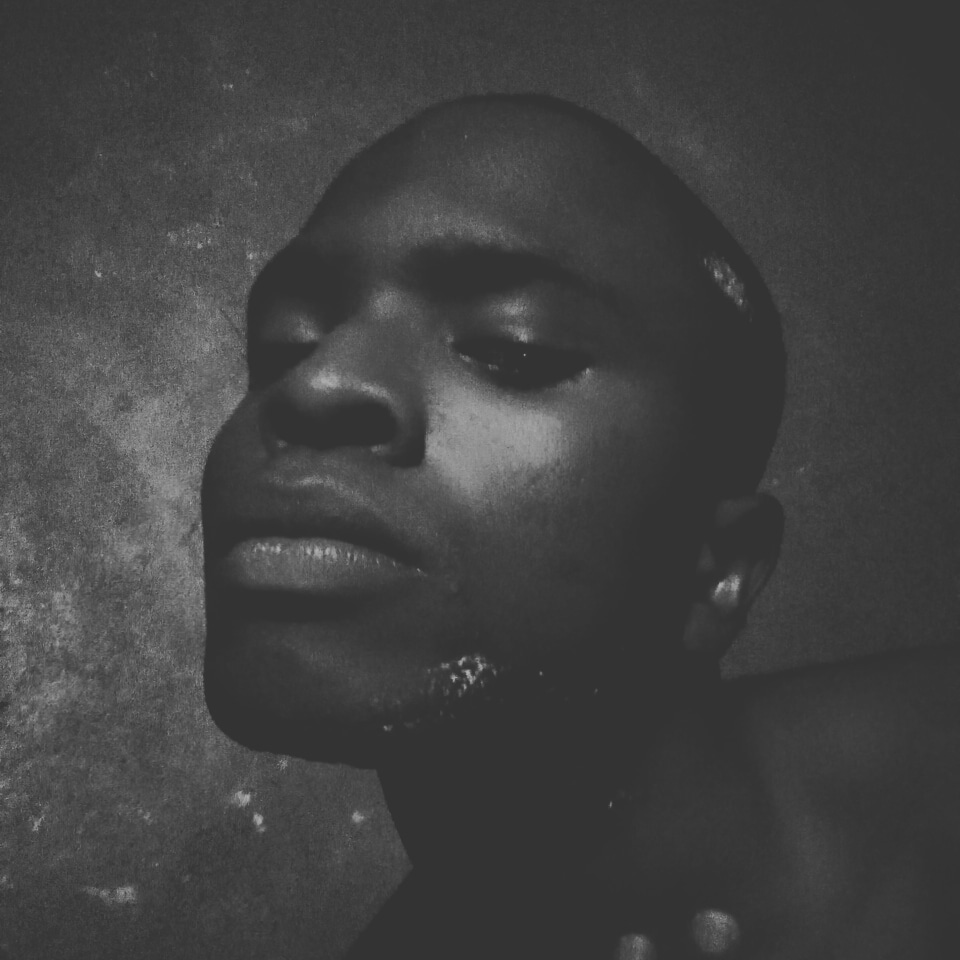

by Innocent Chizaram Ilo

Edited by Julia Rios

August 2018

I

Macaronis are lifeless grubs. Noodles are earthworms made with flour. When short snakes wander into cooking pots they become spaghettis. The difference between a knife and beans is that one has skins and the other skins. Salt breathes life into food. If you twist a mackerel, it will haunt your dreams for two weeks. Don’t turn rice when you’ve added the tomato sauce while cooking jollof rice or it will burn black-black and still come out half-done. Melons fry in their own oil. Palm oil and water are sworn enemies, they don’t mix and they always bicker inside the pot.

My mother thrills me with strange tales about food and cooking in between sprinkling mashed Danjawara pepper on the thin slices of tuna and scouring the snails with an iron sponge. Her pointy fingers and small mouth work in perpetual synch.

Mama owns the restaurant near Dare Ridge, just before you get to the Crossroads of Fate, and all her customers call her Iyawo. The restaurant is a tiny shack with a door so miniature that some of the men will have to hunch just to pass through. The floor is covered with hay and palm bristles and the furniture is sparse—a mud food-counter, a few wooden chairs arranged along the four corners of a long metal table covered with a thin muslin sheet that is ruined by a gapping tear at the center. A cloud of steam, chili, and curry hangs above the customers as they eat, chatter, and fight.

Our customers are all men; from the clean-cut ones who work in exotic offices where they speak into shiny telephones all day and wear tucked-in silk shirts, black blazers and chiffon ties, to the greasy ones who fix pipes, plough fields, and patch roofs all day in their torn polos and baggy jeans. We have never had a girl or a woman come into our restaurant. I once asked Mama the reason and she said women in this town cook their own meals and have no business eating another woman’s food. A huge chunk of my day is spent waiting on these men, reporting those who break or spoil anything to Mama who will send them a bill afterwards, helping Mama cook the meals and, of recent, waiting for the Invisible Customer to come.

II

Mama, Danda (our mule), and I live on the bank of River Bambu. At night, we hear the river grumbling about how our house is occupying its space. River Bambu is plain selfish. A house that is just a tad bigger than the ones Tolu, Ola, Ekwemfi, and I scrawl on the iron bars when we play at Halala Bridge on Saturdays, cannot possibly be occupying the big river’s space. Our house has two rooms, for Mama and me, and a cramped kitchen. Unlike the other houses in the village, ours does not have any room for Papa because there has never been a Papa. There are no pictures of him, no rickety fishing pole in the backyard, no woven waist-cloth in the wardrobe, no anything to prove that a Papa exists or has ever existed in our lives. I always gape at the other children when they talk about their Papas throwing them high up in the air and catching them, letting them sip Ogogoro when their mothers are not looking, threatening to spank some sense into them and howling at everyone any night they come back home drunk. I love hearing these stories of my Papa did this and my Papa did that even though they do not make sense to me.

“Who is feeding you this nonsense?” Mama scolded me the first time I asked her why we don’t have a Papa in our house.

I have learnt to stop asking about Papa. A slight shrug of my shoulder and a quick dose of maybe he is not needed after all or he would have existed if Mama and I needed him did the magic of quietening my question.

III

My mother starts her day after the clatter of the night-soil-men’s pails dies down. The crik-crik of her iron bed bounces off the walls and wakes the whole house. She will wash her face with cow pee and rinse it with a bowl of water she fetched from the river. On some days, usually at the beginning of every month, she walks to River Bambu’s bank with her back turned. This is a good luck ritual she started some years back after Anyaire, the village seer, told her that the other restaurant owners were using juju to steal her customers. Mama’s feet pound the floor like pestles as she walks along the tiny passage leading to my room.

“Adaku. Adaku. What type of daughter continues sleeping when her mother is awake?” Mama will say and give my shoulder a slight nudge. I will turn my face away from Mama’s scowl, stretch my arms, and continue to sleep. After three more attempts, Mama will snatch away the pillow my head is resting on and shout, “I know you are awake. You better stand up or you’ll starve throughout today.”

And Mama means it.

IV

Today, I bump my head against the door as I drag my sleepy self to the kitchen, where Mama is already sieving the ground corn to make pap. The morning is chilly. Frosty fingers are poking through the holes of my wooly socks, nibbling at my toes, numbing my feet. Mama is singing a dirge about a witch who was banished from her home because she fell in love with a human. Her voice rises in the part where the witch and her lover are rolling on the grass at twilight and falls in the part where the witch and her lover are thrown into a pot of hot okra soup because theirs was a forbidden love.

“Is the story real?” I ask.

Mama smiles as she gathers the corn chaff into a plastic bag. “I can’t say if it all happened as the song says but I know the soup pot is real.”

“Where is it?”

“It’s the one over there,” Mama points at a big pot, with broken handles and a chipped bottom, under the kitchen table. Something, maybe a roach, hisses inside the pot as if to tell us that it knows we are talking about it.

“How do you know it’s the same pot in the story?” I collect the bag of corn chaff from Mama and spread it on the tray. I will put the corn chaff on the patio, when the sun comes up, to dry and feed the chickens with it in the evening.

“When I was still a little girl, I placed my ears on the pot and heard the voices singing. I asked my mother and she told me the story.” Mama washes off the bits of ground corn on her hands and wipes them dry with a rag.

“Can I check to see if they are still singing?”

“No. We have work to do.”

There is something theatrical and musical about the way Mama cooks. She can turn little things like chopping onions and dicing peppers into a huge concert. Every object in the kitchen understands Mama. She speaks their language and, in some way, they also speak to her. She whispers to the kettle not to scald her as she lifts it off the stove with her bare hands, she tells the pot to be tender on the beef and not to make it soggy, she reminds the oven not to burn the bread, she laughs every time the pot tells her that fish oil tickles it, and she begs the frying pan not to blacken the potatoes or over-bleach the olive oil. Mama and her kitchen talk and laugh like long-ago-friends who just ran into each other in a crowded bus station. Mama assures me that I will begin to understand and speak this secret culinary language when the time comes.

“Are you going to stand there and watch me all day?” Mama has stopped singing. Her eyes, two shiny black dots swallowed in white, are glaring at me. “Come and start picking the beans. Do it outside, where there is light. I don’t want the customers complaining of sand and stones in the porridge.”

Mama switches to another song. This one is about a sparrow who lost her way in the desert. Heartbroken and alone, the sparrow begs for death to come, for the scorching sun to set her wings on fire and for the cold night to freeze her heart. Death decides to yield to the sparrow’s request on the night her family comes back for her. Mama changes to another song before I could ask her if this story happened. The new song is about a mermaid who was left on a beach by poachers.

Mama’s songs always tell sad stories.

By the time we are done cooking, Mama is singing the tenth song. I help her load the pots of jollof rice, egusi soup, foo-foo wraps, stew, and pasta onto the cart in the backyard. I yoke the cart on Danda’s neck while Mama goes back into the house to dress up. Danda snorts under the burden of the cart and does not move until I rub her sides.

“I’ll get you fresh hay today,” I whisper into Danda’s ears. She brays. “We may even stop at the market for a soya-bean husk treat.”

Danda has been our mule for as long as I can remember. When I was littler, her now worn-out hooves had more gleam, and her legs, which have thinned into chopsticks, were studier.

“Adaku, hurry up. We don’t have all day. I don’t want to miss the morning customers because of you.” Mama shouts. She is already at the gate.

I pat Danda’s head and she begins to pull the cart.

“Were you laying eggs in there? Gbo Adaku, was that what kept you in the backyard that long?”

“I was not laying eggs.” I frown. “I was talking to Danda.”

“The mule?”

“Yes.”

“But it’s just a mule.”

Mama has a knack for reducing things she could not wrap her head around to it’s just a. I remember my first sleepover at Ekwemfi’s house. Ekwemfi had pointed out that I didn’t have a bellybutton like her, like everyone else. “It’s just a bellybutton. Not everyone has it. I don’t have it,” Mama told me the next morning when I asked her why I didn’t have a bellybutton.

And because Mama dismisses unusual things with the wave of a hand, I have decided not to tell her about the Invisible Customer.

V

The Invisible Customer is not really invisible-invisible. I can see him or, as he puts it, he has chosen me to see him, for now. He came to our restaurant two weeks ago. It was evening and the last customer had just left, after threatening not to come back if Mama does not add fisi for him the next time he orders yam porridge. I was wiping the tables when the door groaned open. A gust of lukewarm breeze surged into the room and tickled my palms. I knew something or someone had come in. The chairs shifted and the table squeaked. That was when the Invisible Customer removed his coat and revealed himself. He had a small face sprinkled with freckles, a pointy nose, popped-out eyeballs, and two fingers were missing on each hand. He smiled and waved at me. I wanted to scream but I couldn’t. My tongue felt like a nail-board ready to sink into my upper palate if I screamed.

“Is this Iyawo’s place?” He asked.

“Yes.” I stuttered.

“Ah, at last. I knew I wouldn’t miss this place. Hasn’t changed much since the last time I visited.” He exhaled green gas from his nose.

“You’ve come here before?” My feet began to move themselves towards the chair he was sitting on.

“Yes. Just before you were born.”

“Who are you?”

“She didn’t tell you about me. Ah, people cannot be trusted.”

“Who didn’t tell me?”

“Your mother.”

“What is your name?”

“Call me Aguru or the Invisible Customer.”

“Adaku!” Mama shouted from outside. “I need extra washing soda.”

My feet refused to move. Mama continued shouting. It was only when she stormed into the restaurant and slapped me that I snapped out of the trance.

“Are you deaf?”

The Invisible Customer was gone.

From that evening, the Invisible Customer has come to the restaurant every evening after the last customer has licked his plate clean. He brings me a beautiful gift on each visit. Brass trinkets, cowries for my braids, wooly blankets, harmattan-globe,s and wooden dolls. He once showed me his enchanted chessboard and I marveled at how the huge box could fit into the tiny pocket of his coat, to which he said that sight can be deceiving. The chessboard is a shiny thing with pieces that can move themselves. On days when the evening drags on and Mama is taking forever to wash the plates, he performs some magic like pulling out a rabbit from the back of my ear or spin his head.

Yesterday, he told me he was going to talk to Mama today.

VI (A)

Two customers are already waiting at the door when we get to the restaurant. Mama instructs me to go inside and set the place up while she greets the men. One of the men is coughing hard. A lit yellow cigarette sticks out between his lips. The other man keeps spitting into the open drainage like he swallowed bile. Mama says something and the men laugh. They are miners looking for diamonds at Onuiyi Cave. I can tell this from the rusty helmets hanging loosely around their necks, their muddy coveralls and leather boots. Mama is the only food seller in the village who loves having miners in her restaurant. Although miners are wont to be short on cash and always eat on credit, Mama understands that they will pay for their meals with diamonds, gold, and lumps of coal when their shovels strike luck.

“Any luck finding gold?” Mama asks.

“The ground is getting stingy these days,” the man with a lit cigarette answers.

I put my back into placing the pots on the food counter, dusting the chairs, pouring fresh hay on the floors, and checking the roof for cobwebs after I notice Mama’s eyes darting towards the restaurant. This is warning enough to remind me that she will whip my bum real silly if she comes in and meets the restaurant untidy because I was busy eavesdropping on adult gossip. I already know how Mama’s conversation with the miners will play out; they will ask her for meals on credit and she will agree as she always does.

Nothing interesting happens during the morning rush. The customers queue in front of the counter and collect their orders—bean, corn porridge, and brown bread steamed in fish sauce, all wrapped in banana leaves. They settle on the chairs and munch away. The noise is tapered down to a few chuckles and murmurs of early morning gossip—who got beaten up by his wife last night because he had a drop too many and whose son put the baker’s daughter in a family way.

Mama knows the names of all the customers and talks shop before handing out their orders to them.

“Ikem, I hope your knees have healed. Those bellows are not going to work themselves.”

“Zimuzo, I love the cane-cupboard you made for Mrs. Ifezulike. Can you make one for me?”

“Okoro, you have to tell me when next you harvest your corn. I don’t want to haggle with those women at Ogige Market and still come back with a mound of bitter corn.”

VI (B)

The restaurant turns into a madhouse in the afternoon and this, the intense stomping of feet and brash howling, drains me out. Work is over so the customers troop into the restaurant like swarms of locusts. They are bawling. They are slamming their sweaty fists on the table. They are demanding food. When Mama tries to calm them down they begin to chant; “Iyawo, give us our food.” A cluster of men are arm-wrestling at the west end of the table. Mama grabs the man who wants to pee into the water jug by the neck and kicks him out of the restaurant. I spill tomato sauce on a customer and topple over the water jug twice as my eyes scan the room for the Invisible Customer. Mama nearly knocks off my nose when I hand her a packet of salt instead of the scouring powder she asked me for. She pulls at my ears and asks if they are for fancy.

VII

The day is almost over. Except for the drunk man who chewed his beer mug, today passed like every other day. Mama sends me to the shop across the street to buy washing soda as the last customer stands up to leave. People are talking in raised voices when I come back to the restaurant. I open the door to see Mama and the Invisible Customer.

“She is back. Tell her the wickedness you did,” the Invisible Customer says to Mama.

Mama eyeballs the Invisible Customer and turns to me. “Adaku, come here.”

I trudge to where Mama is standing. “What is going on here?” I ask. “Have you two met before?”

“Of course we have. This woman stole you from my pocket.” The Invisible Customer gestures towards Mama. “Twelve years ago, I wandered into this place. I was hungry and tired so I fell into her arms. She made me the sweetest food I have eaten in my life and she slipped you out of my pocket when I fell asleep.”

“I didn’t steal, I was just collecting what was due for the food and lodging I offered you.”

“How can one steal a baby from your pocket?” I ask.

“This,” the Invisible Customer touches the pocket of his trousers, “contains powerful magic. It grants any type of wish. Your mother wished for you and you came to life.”

“Why did you wait for all these years to pass before coming to take her away from me?” Mama sniffs back the tears clouding her eyes.

“Ah, what is the fun of taking her away early when she has not meant much to you. Adaku, pack up your bags we have a long way to go.”

“Can I at least make dinner for the two of you?” Mama pleads.

“No, woman. The last time you made me dinner led to all this…”

“At least for the sake of the child. She needs all the energy she can get to journey with you to the other end of the world.”

The Invisible Customer nods. “Okay, but I am doing this for the child.”

“Where are we going to?” I ask the man.

“To the Land Of Pink Shadows.”

VIII

I have always imagined living vast lives; in a strange castle painted with a unicorn’s blood, on a caravan of three-eyed pirates, in a town where the sun never sets or on an island bounded by a golden reef. Imagined it, dreamt of it, but never thought it would happen. As Mama, the Invisible Customer, and I walk home, it became crystal clear that my dreams of living a life elsewhere are ebbing towards reality.

“Do you want to join me in the kitchen?” Mama says when she comes into my bedroom.

“I have to pack for my journey.”

“Adaku, there is always time to pack for a journey.”

“Won’t the Invisible Customer get angry if it’s time to go and I am not yet ready.”

“His name is Aguru and not the Invisible Customer. He just has an invisible coat.” Mama quips and sits on the bed. She pushes the pile of folded dresses on the bed to create space for her to sit.

An empty silence fills the room.

“You are letting him take me without a fight?”

“Women like us don’t fight with words. We fight with food.” Mama looks into my eyes and smiles. “Come and join me in the kitchen.”

IX

The mountain of jollof rice on the wooden platter reaches towards the ceiling. Mama heaves a sigh and breaks into a song. This song is strange, Mama has never sung it before. Her voice flattens as she employs the food to become smaller. As she sings, the mountain of food shrinks and shrinks until it is the size of a plateful. Mama heaps another mountain of jollof rice on the platter and continues singing. She does this until ten mountains of jollof rice shrinks to a plateful. Mama carries the platter into the parlor and places it in front of the Invisible Customer.

“It is not in our custom to leave a woman’s house without tasting her food.” Mama says to him.

The Invisible Customer looks the platter over before picking up his spoon. Scoop after scoop, the platter of jollof rice remains as it is. He continues to eat until his stomach bloats like a frog’s, until rice grains start shooting out of his nose, his eyes, and his ears, until he falls forward—his head buried halfway in the platter of jollof rice. Mama drags him out of the house and hurls him into the cart outside.

“We are going to River Bambu to take care of some business.” Mama says. “I should have burnt the pesky thing when he was snoring on my couch twelve years ago. But it’s no use, he always finds a way to come back.”

Danda groans all the way to the river. Her legs hurt. She has barely rested them since we came back from the restaurant. But Mama continues dragging her down the rocky path to River Bambu. When we get to the river, Mama gags Aguru’s mouth, ropes a stone around his neck and rolls him far into the water. The river burps as he sinks to the bottom.

“What happens if he comes back?”

Mama dusts the sand off her palm. “We will still kill him.”

“Why?”

“Adaku, you have to understand that women like us must do this if we don’t want to be wiped off the earth’s surface.” Mama pauses to catch her breath.

“What do you mean by women like us?”

“Do you remember that song about the witch and her lover who were thrown into a pot of okra soup?” I nod and Mama continues. “The witch cursed Nli, the woman whose pot was used to cook the okra soup that killed her and her lover. She said she will never have children like other woman.”

“Who is Nli?”

“My mother’s great-grandmother.” Mama wipes her brow. “Adaku, the only way women like us can have children is by hoping that one day, the aroma of our food will attract a hungry spirit like Aguru whose pockets can grant wishes. My mother did it, my mother’s mother did it. You, your daughter, your daughter’s daughter will also do it. This is our only assurance for our existence.”

“But he was nice. He brought me gifts anytime he came.”

Mama presses my palms together and says, “With time you will understand. Let’s go home. Tomorrow is not going to cook for itself.”