Mar 18, 2017 | news

A Little Sunshine

by Pablo Defendini

One of Fireside’s core values is transparency: We think that it’s important to be forthright with the way we run things around here, in order to build trust with the the wider world. Our commitment to being transparent also allows us to engage with difficult subjects more effectively—we think that doing so out in the open cuts down on bullshit drama and he-said-she-said shenanigans. We strive to be honest, open, up-front and straightforward, which is why when we received an odd email last week, we declined to engage with it beyond what we posted publicly.

Tonight, the author of that email made good on their promise and published their report, albeit still pseudonymously. After just a few hours of getting some pretty valid critique on twitter, citing “receiving threats,” they decided to take it down.

Well, we think that’s a shame—now that they’ve published it, their work should be available for the rest of our community to refer to and to engage with. So we’ve taken the liberty of copying their original Medium post, and pasting it in here.

What follows is unaltered copypasta. Any subsequent edits we make will be purely for visual styling and formatting reasons (because I’ll be damned if this stuff is gonna fuck up my nicely-designed site). As always, you can check our receipts at our public GitHub repository, to make sure we’re sticking to our word (see, that’s how transparency works. Isn’t that useful?)

¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Okay, here we go:

Bias in Speculative Fiction

Preamble — There is a race problem in speculative fiction and we need to make an effort to understand its causes. The data matters even when it doesn’t go our way. Especially when it does not go our way. It is through the collision of error and reality that we refine our thinking. Statistics resolves epistemic questions where ad hominem attacks do not.

Fireside Fiction’s July 2016 report “Antiblack Racism in Speculative Fiction” [FR] purports to have found pervasive racism in speculative fiction publishing. With 38 out of 2,039 (1.9%) published works authored by black-identifying authors, there is unquestionable underrepresentation. FR ascribes this disparity to widespread anti-black editorial bias. We share Fireside’s concerns about underrepresentation and commend its authors for raising awareness. At the same time we find the report to be fraught with error.

Complex problems typically have complex causes. Large effects are easy to identify, but we can overlook many small effects. In this critique, we address potential causes of bias and quantify their effect sizes. We demonstrate that the data presented in FR are explicable in part by demographic data and are consistent with random processes. Finally, we briefly suggest ways to study bias in greater depth.

Fireside Fiction refused to comment on this document, writing “¯\_(ツ)_/¯”

Demographics

We begin by addressing demographics, since FR makes a demographic argument. The report assumes that 13.2% of speculative fiction submissions come from black authors, commensurate with the black population at large in the United States. This assumption does not match any available demographic data.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s ACS Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS, 2015) finds 159,484 working writers and authors in the United States. Of this population, only 6,423 writers (4%, ±1,538) are identified by the survey as black. Similarly 7,086 (4%, ±1,800) identified as Asian. As of 2011, persons of African ancestry made up just 5% of tenured and tenure-track faculty among the top 50 MFA programs. A 2015 report by the Association of Writers & Writing Programs found that 9.1% of MFA students were identified as Black non-Hispanic.

Demographic data from the Department of Education (NCES IPEDS) shows that 5% of creative writing (code 231302) and 7% English (code 23) Bachelor’s degrees were granted to black-identifying students.

In Roxanne Gay’s 2012 article, Where Things Stand (The Rumpus), she found that of 742 books reviewed by The New York Times, works by black and Asian authors each comprised 4% of the total. Her survey is consistent with the demographics presented in PUMS. This supports the hypothesis that the publication rate of black Americans mirrors their representation in the pool of working authors in the United States as opposed to broader population.

All the data suggests that black and non-white Americans work in writing professions at a lower rate than their representation in the general population. While this is suggestive of systemic bias, it does not demonstrate editorial bias contrary to FR’s claims. If slush pile demographics match the demographics of creative writing degree recipients, this effect in isolation would reduce speculative fiction publications by black authors by 62% compared with the naïve expectation.

Tokenism

One contention made in FR is: “…we are seeing far too many [magazines publish exactly one black author] which is suggestive of tokenization.” This is testable.

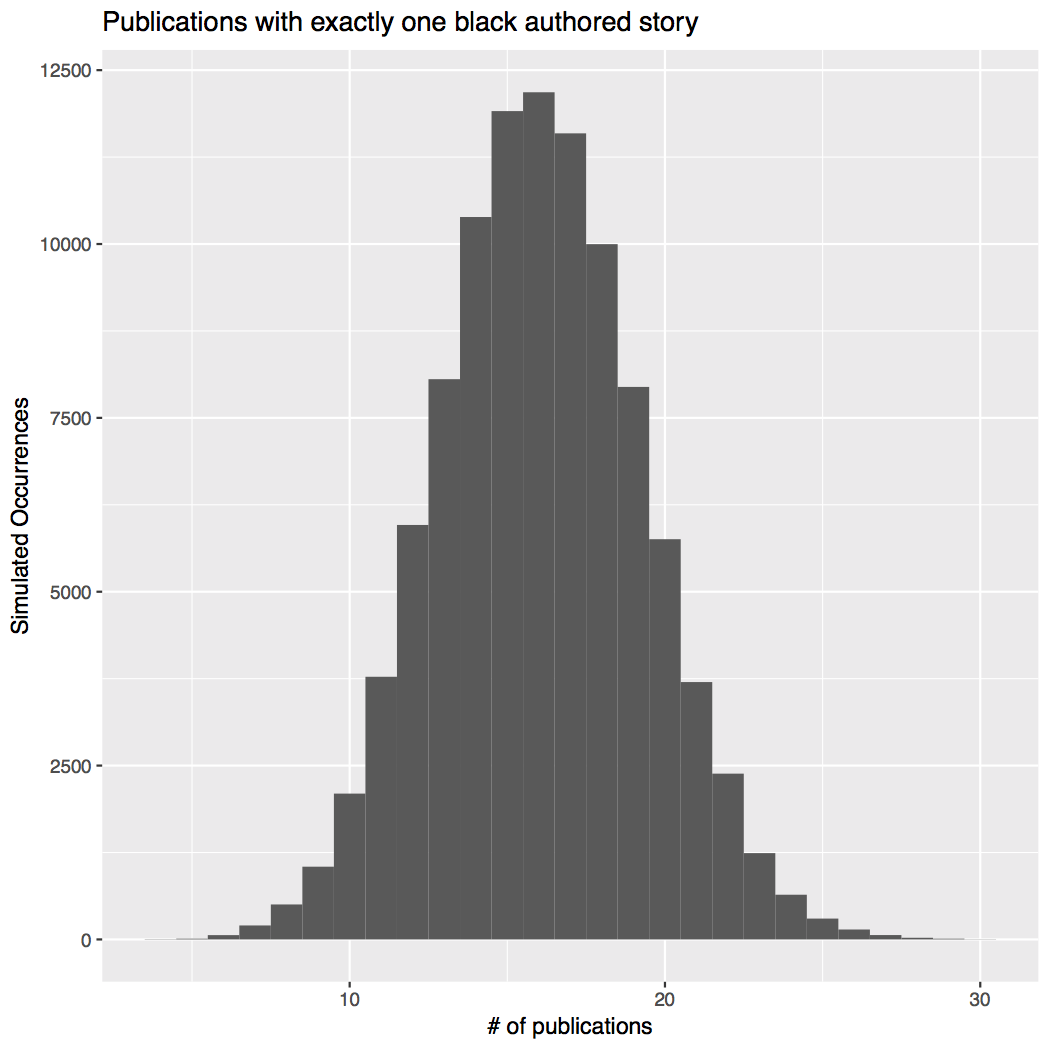

Fig 1. Publications with exactly one black authored story. Permutation test median: 16, 25th/75th percentile: [14,18] The observed value was 15.

In Fireside’s dataset, there are 38 stories written by black writers among a total of 2,039 stories. (By the pigeonhole principle at least twenty-five magazines in the data set will not feature a black writer.) Fifteen magazines published exactly one story by a black author. To test tokenism we use permutation testing: put all 2,039 stories into a deck, then randomly allocate them to magazines based on publication volume. Terraform gets 59 stories, Fireside 32 and so on.

How many magazines do we expect to feature exactly one black writer under this model? We test whether this is meaningfully different from the 15 observed.

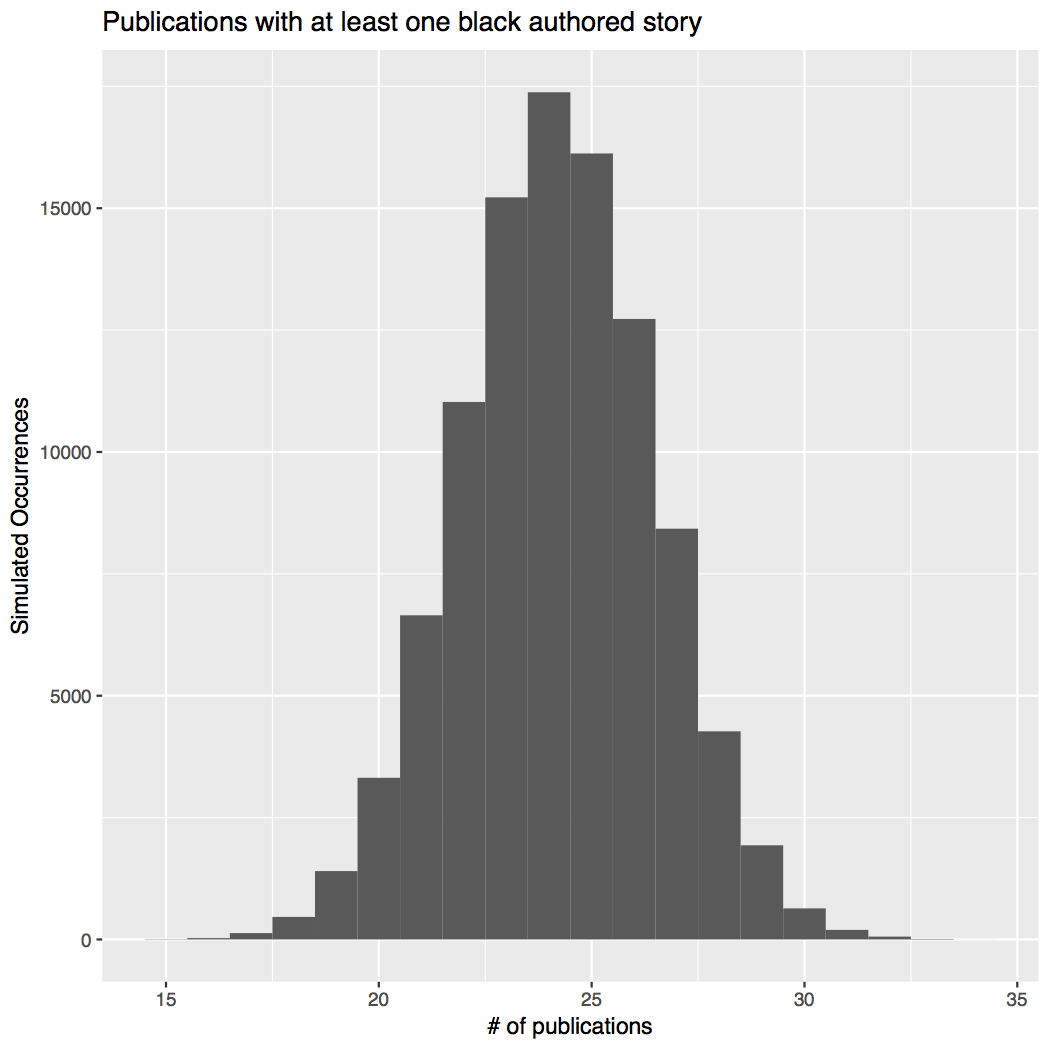

Fig 2. Publications with at least one black authored story. Permutation test median: 24, 25th/75th percentile: [23,26] The observed value was 24.

Permutation tests converge to an average of 16.04 magazines featuring exactly one black author. The 25th and 75th percentile were 14 and 18 respectively (Fig 1). The 95th percentile was 21. The observed data is not meaningfully different from chance.

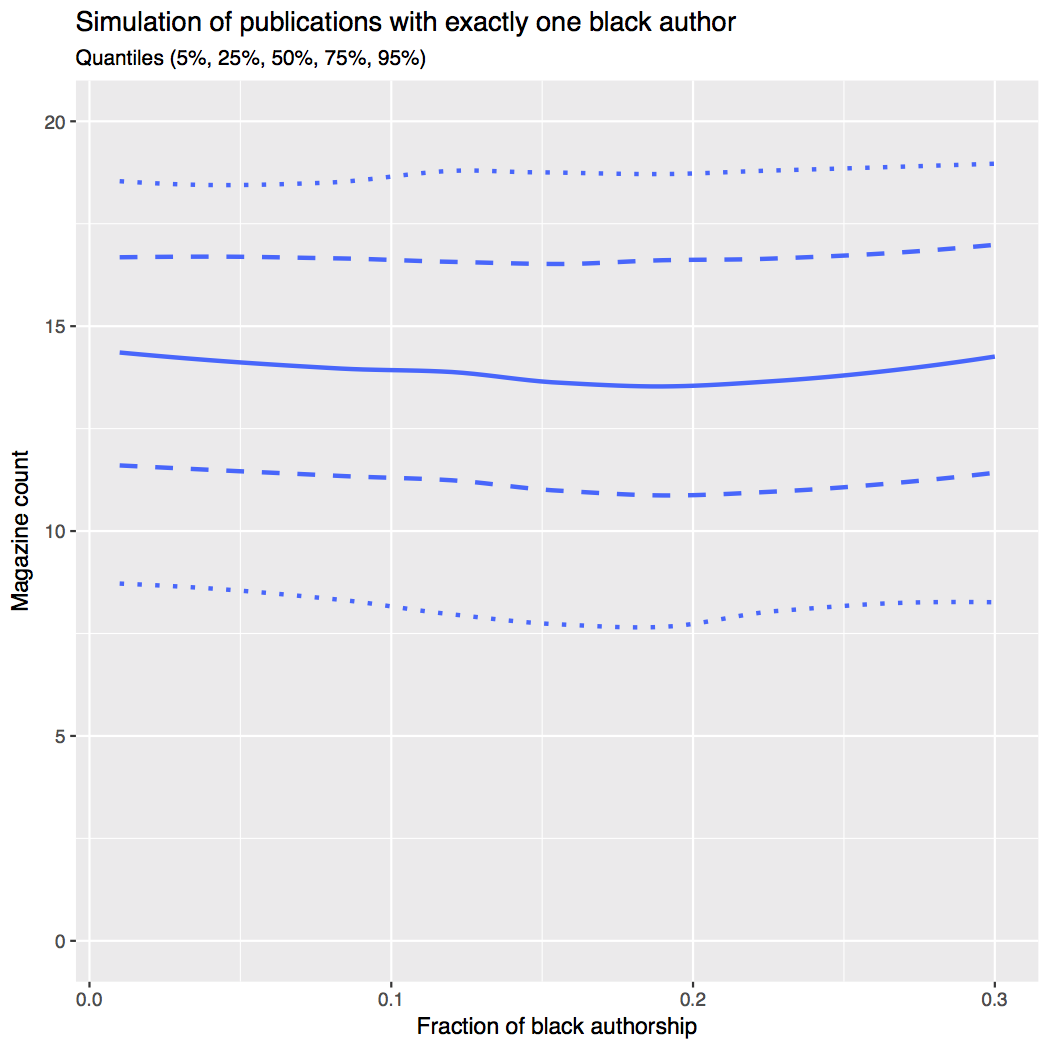

Fig 3. Distribution of publications with exactly one story by a black author from permutation tests. Readers may note similarities to the coupon collector’s problem.

Similarly we can ask: Given 38 black authored stories, how many magazines do we expect to contain at least one? We repeat the sampling process described above, allocating exactly 38 stories among the magazines. Over 100,000 simulations the median was 24 out of 63 journals featuring at least one black authored story (Fig 2). The FR data counted 24 journals featuring at least one black authored story and 15 with exactly one. This is consistent with expectation.

Finally, we search the parameter space. What is the distribution of publications with exactly one black author as the fraction of black authored stories change?

Here we varied the share of black authored stories from 1% to 30% and generated 1.5 million permutations (Fig 3). Under this test the observed data is consistent with any proportion of black authorship in the range.

Multiple Hypothesis Correction

In its conclusion, FR states “[T]he fact that Terraform … appears to have published 8–9% black authors suggests that the number of stories by black writers within the average submission rate is greater than 2% and likely closer to Terraform’s average.” At the same time, Brian J. White’s companion essay “Fiction, We Have a Problem: It’s Racism” points out that in 2015, black authors wrote 9.4% of their stories, but as of July 2016 they had featured zero black authors.

What’s going on here? Why the year to year variation? Is Terraform’s publication rate surprising?

The answer is two-fold. First, as FR points out, the numbers we’re dealing with are small. This makes them susceptible to small, random fluctuations. The second, more subtle, factor is multiple hypothesis testing.

Fireside did not set out to ask the question “Does Terraform feature works by black authors at a rate in excess of chance?” Instead, they implicitly formulated sixty-three dependent hypotheses and concluded post hoc that Terraform was well performing compared to its peers. Using Fireside’s test, we would expect about 2 magazines to show significantly more black authors than their peers, under an uncorrected p-value. We’d also expect that at least one magazine should appear significant 96% of the time. Here we should apply multiple hypothesis correction. This correction is simple. Instead of testing at a significance threshold of p=0.05, we use p=0.05/63 or ~0.0008. Again we employ permutation testing. At the 0.05 level it should surprise us if Terraform publishes three or more stories by black authors. To surpass the stricter, corrected threshold, we require six.

Terraform’s 2015 publication rate does not differ significantly from chance and we fail to reject the null. No other publication is significantly different from expectation, either in a positive or negative direction. A time series analysis may provide enough statistical power to identify non-random effects.

Distributions

The misuse of the binomial distribution in FR is a significant cause for concern. Under the binomial distribution, we treat each publication as an independent random event with some fixed probability of occurrence. FR assumes that each submitted submission should have a 13.2% chance of black authorship. The probability of observing their data subject to this assumption is 3.207x10^–76. They provide no rationale for using population rather than occupational rates. Suppose instead that science fiction slush is submitted from a pool of professional writers uniformly at random. Under these assumptions we assume that there’s a a 4% probability that a story is written by a black author. The data becomes 68 orders of magnitude more likely. Still unlikely, yes, but this demonstrate the impact of our assumptions.

One prolific author of short fiction placed seven works of short fiction in professional markets during 2016. Many professional magazines maintain an acceptance rate below one percent. Assuming each submission is equally likely to be published we should expect this author to have made in excess of 900 submissions. Even among the most productive writers, such output is infeasible and the binomial distribution cannot satisfactorily explain this result. Famous writers have an almost tautological knack for getting published. Any reasonable model must account for this.

When your data doesn’t fit your model, start by questioning your model. We contend that the binomial fails to meaningfully describe speculative fiction publishing. As an alternative to the binomial we propose an empirical approach based on observed data.

An Empirical Model

We examined the distribution of short fiction publications per author for 2015 and 2016. Our investigation excluded single author publications. We further excluded works that appeared as part of a series. In 2015 there were 2294 publications by 1629 distinct authors, and in 2016 there were 2193 publications by 1518 authors. In this two year span, authors with exactly one annual publication made up 76% of the population but accounted for only 54% of writing. This drives up the sample variance which can compound existing racial disparities. Well published authors are more likely to get published again. This crowds out newcomers who are may be more diverse.

With the 2015 data, we make random racial assignments per author with the binomial distribution. We vary the percentage of black authors in the simulation. With this distribution, we compute the posterior probability for each input percentage given the data observed. (For example, “If 2.5% submitted stories are by black authors, left to chance how likely is it that we’ll see 1.9% of publications by black authors?”)

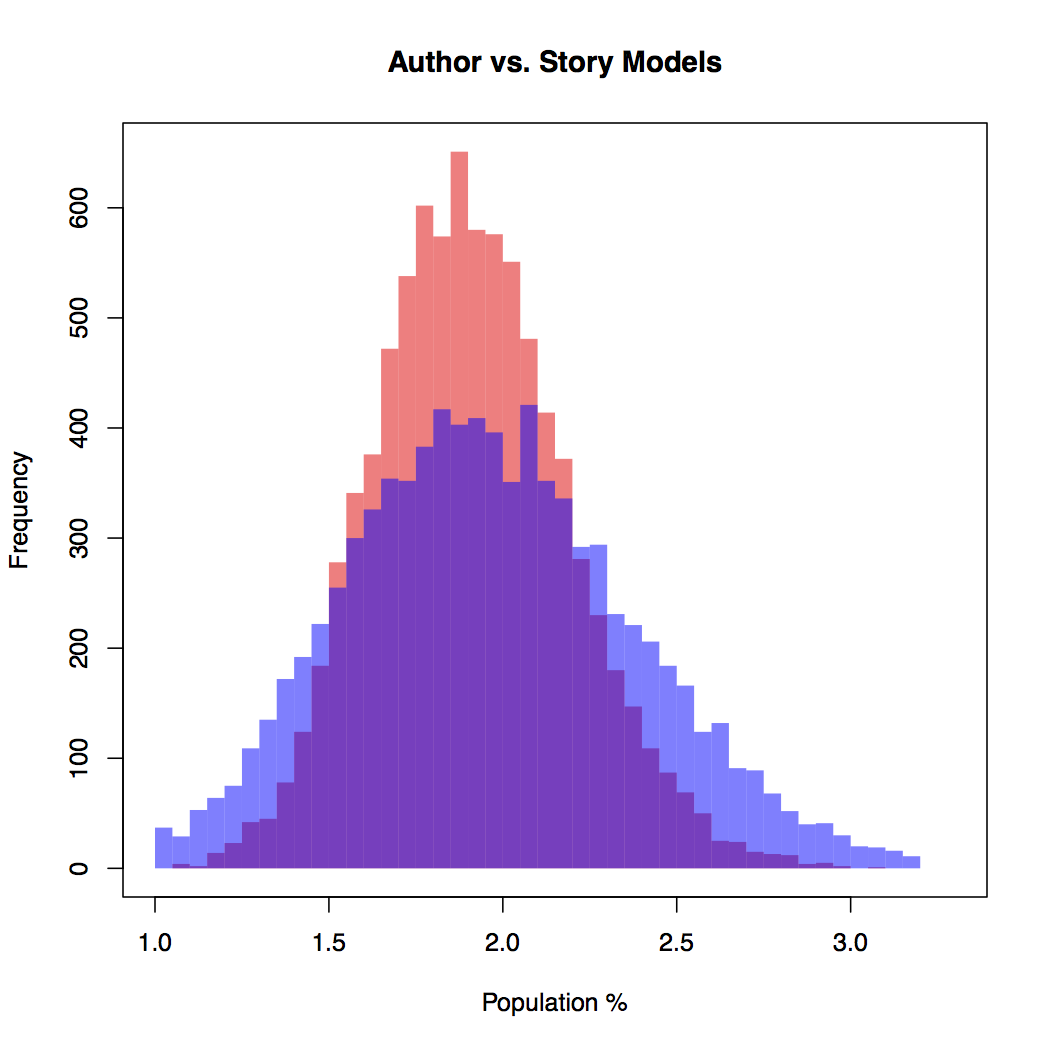

Fig 4. Posterior Probabilities. Author Binomial Model in Blue. Story Binomial Model in Red. The presence of popular authors increases the variance.

While the two distributions had the same central tendency, the binomial author model exhibited increased variance. (Fig 4). Under the story model, for example, the probability of observing FR’s data given 2.3% black slush authorship is equal to 2.55% authorship under the author model.

We emphasize that this model underestimates the effect size. It only looks at effects within a single year. An analysis of the Internet Speculative Fiction Database found 33,565 distinct works of short speculative fiction by 12,360 writers from 2002 to 2016. During this interval, authors with five or more publications published 53% of all new fiction while making up only 10% of the population. In a single year, however, authors who were published more than once only made up about 25% of all publications. If only 1-in-10 debut authors join the ranks of highly published authors, speculative fiction demographics will change slowly.

Conclusions

The rate at which black authors appear in speculative fiction publishing is not proportional to the overall black population in the United States. It is half that of the population of black writers. There are non-random effects at work. However, FR presents no statistically significant evidence to support their central thesis of systemic anti-black editorial bias.

Publishing is the end of a long pipeline. Demographic data shows that black Americans are less likely to acquire degrees in creative writing, less likely to enter MFA programs, and less likely to be employed in writing. This suggests systemic bias, but does not implicate editorial racial bias per se.

We have also shown that the data does not suggest the existence of tokenism in speculative fiction. Instead, the distribution is consistent with a Poisson process.

The binomial story model presented by Fireside is not appropriate for at least the two reasons discussed here. It ignores all available labor data and fails to account for frequently published authors and stabled authors. Accounting for these effects provides a plausible explanation for a 64% reduction in published stories by black authors versus expectation.

Data analysis is hard and we are concerned by the lack of technical acumen shown in the Fireside report, especially in light of its provocative claims. The report makes no serious effort to effort to examine the data in depth and fails to perform proper null hypothesis testing. We encourage anyone pursuing this sort of analysis to consult with social scientists.

The point of looking at data is to better understand the world. We challenge our assumptions. The beliefs that weather the storm are stronger for it. Yes, we believe that anti-black bias exists in speculative function. We’d need to be stupid or craven not to. This has no bearing on the analysis in FR. Pretending otherwise does nothing to further diversity.

Further Work

Our analysis of the FR data is incomplete. How can we refine it?

In an interview with Fireside Fiction, N.K. Jemisin stated, “[t]here’s a gigantic market of self-published and small press published black fiction that kind of eschews the whole traditional published market”. How do self-publishing demographics compare with traditional publishing? This should provide a better baseline for determining submission rates. Can writer surveys at submission time establish ground truth data?

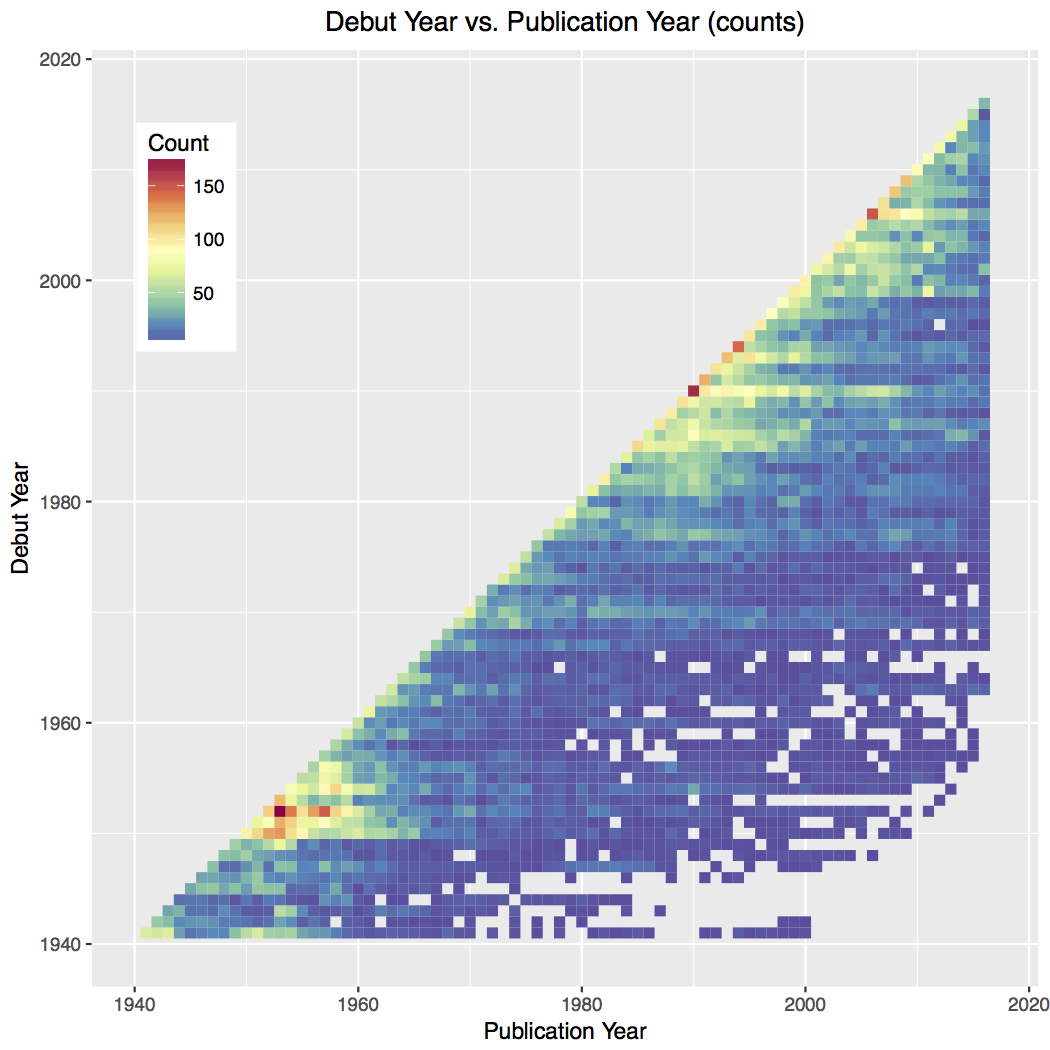

Fig 5. Annual cohort publishing output, counts. A hotspot in the lower left shows a fiction boom following World War II.

Publishers tend to feature authors repeatedly. In 2015, over 30% of short story publications were authored by writers who had placed writing with the same publisher in years past. To what extent does this limit opportunities for new writers?

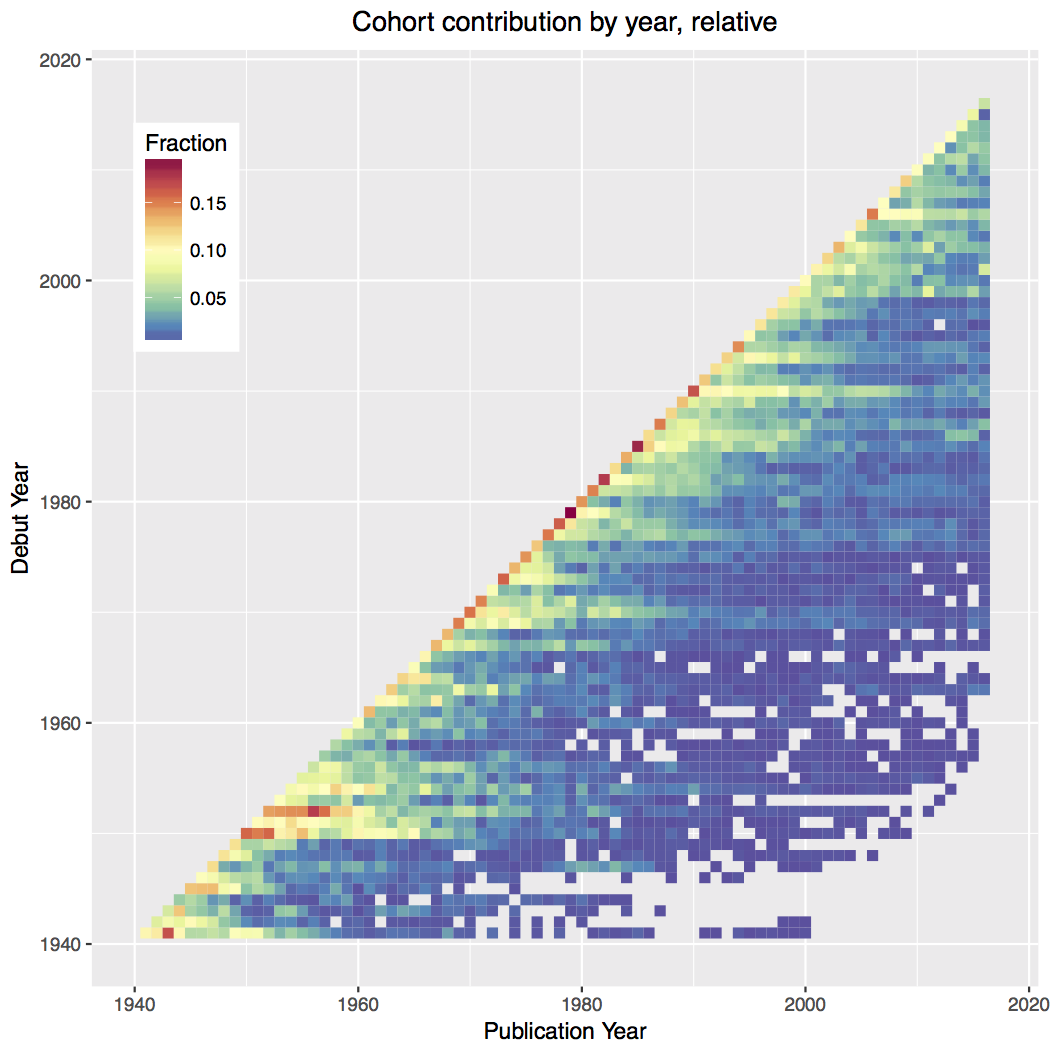

We briefly surveyed effects over time by organizing authors into annual cohorts based on their debut year (Figs 5–7). Only a small number of new authors appear in professional markets each year. Established writers are more likely to submit and probably more likely to have their submissions accepted. Authors who first appeared in the 1980s continue to publish significant amounts of work today. The share of work produced by debut authors has decreased since the 1980s (Fig 6). This is suggestive of a founder effect perpetuating existing biases. Does reading slush blind lead to an increase in the representation of new or more diverse writers? What is the impact of encouraging aspiring authors to submit?

Fig 6. Annual cohort publishing. Normalized by column. There are fewer author debuts in the 2000s vs the 1970s and 1980s. Authors debuting before 1940 are included in the dataset, but are not shown in the visualization — early years may not sum to one.

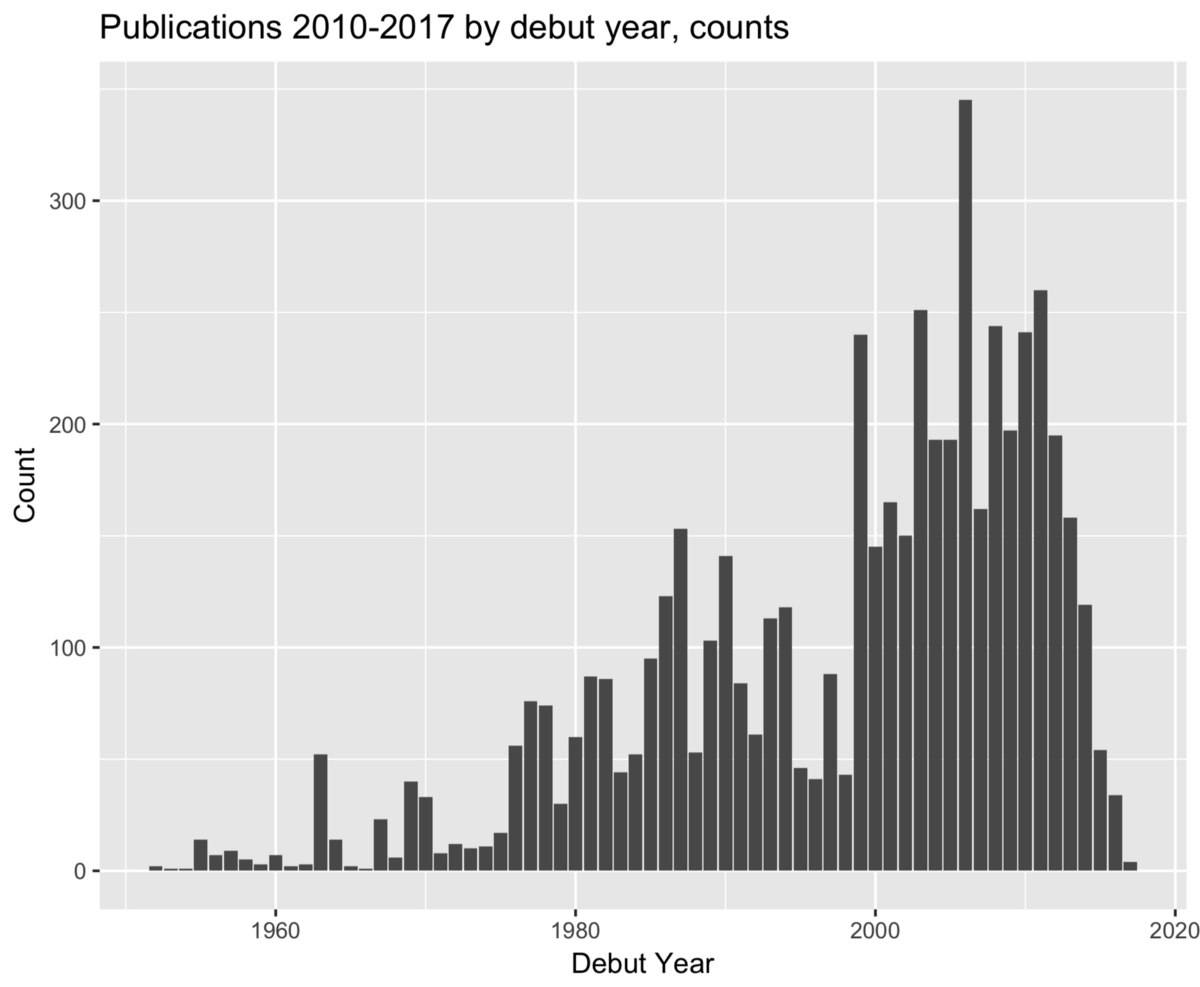

In reviewing data from 1940 to 1999, we found that the mean author age at first magazine publication was 36 (n=2720). After 2000 the mean debut age rose to 40 (n=1020). This suggests a longer road to publication. Per story, the median duration between an author’s debut and publication year rose. This indicates that authors are enjoying longer careers. Between 1940 and 1980 it climbed from 7.5 years to 10.6 years. This decade saw a high of 14.6 years (Fig 7).

Fig 7. Debut year distribution for recent publications, counts. All formats (magazine, novel, etc.)

What socio-economic factors can we control for? Among 1999 college entrants, parental income and educational attainment accounted for a 6% difference in graduation rates. NPR’s Planet Money conducted an analysis of longitudinal BLS data. They found that students who grew up in high-income households were more likely to study the arts. Factors like these will compound to produce disparate impact.

We welcome any further efforts to quantify causal factors impacting demographic representation across speculative fiction publishing.

Appendix

Methodological Questions

We posed four methodological questions (and a fifth question unrelated to methodology) to Fireside Fiction. They refused to answer our query.

Our questions are reproduced verbatim below. Question 3 contains a minor technical error.

1— What data sources did you use in compiling the report?

2— Which 38 stories were written by black authors? We hypothesize that highly published authors keep getting published, crowding out newcomers. This founder effect should perpetuate a majority white authorbase.

3— What was your procedure for censoring missing data?

4— Why did you assume that the portion of black authored slush should be 13.2%? In the United States only 4% of professional authors are black. This is unquestionably atrocious, but doesn’t necessarily imply racism in speculative fiction publishing.

Who are you?

We’re a group of writers and editors. We have chosen to publish under a collective pseudonym. Our identities would only serve as a distraction. As Cornel West recently wrote:

All of us should be willing — even eager — to engage with anyone who is prepared to do business in the currency of truth-seeking discourse by offering reasons, marshaling evidence, and making arguments. The more important the subject under discussion, the more willing we should be to listen and engage — especially if the person with whom we are in conversation will challenge our deeply held — even our most cherished and identity-forming — beliefs.

If you don’t believe us, just try it yourself. All of our methods are easily replicated and don’t rely on appeals to authority. What we have said is independent of identity. It’s no less true if we’re your staunchest ally or most bitter foe. This text can live or die on the merits.

Technical questions and comments should be sent to [email protected].

Acknowledgements

We thank the many anonymous readers of early drafts for their valuable feedback and technical guidance.