Dirt Under the Nails

by Aaron Menzel

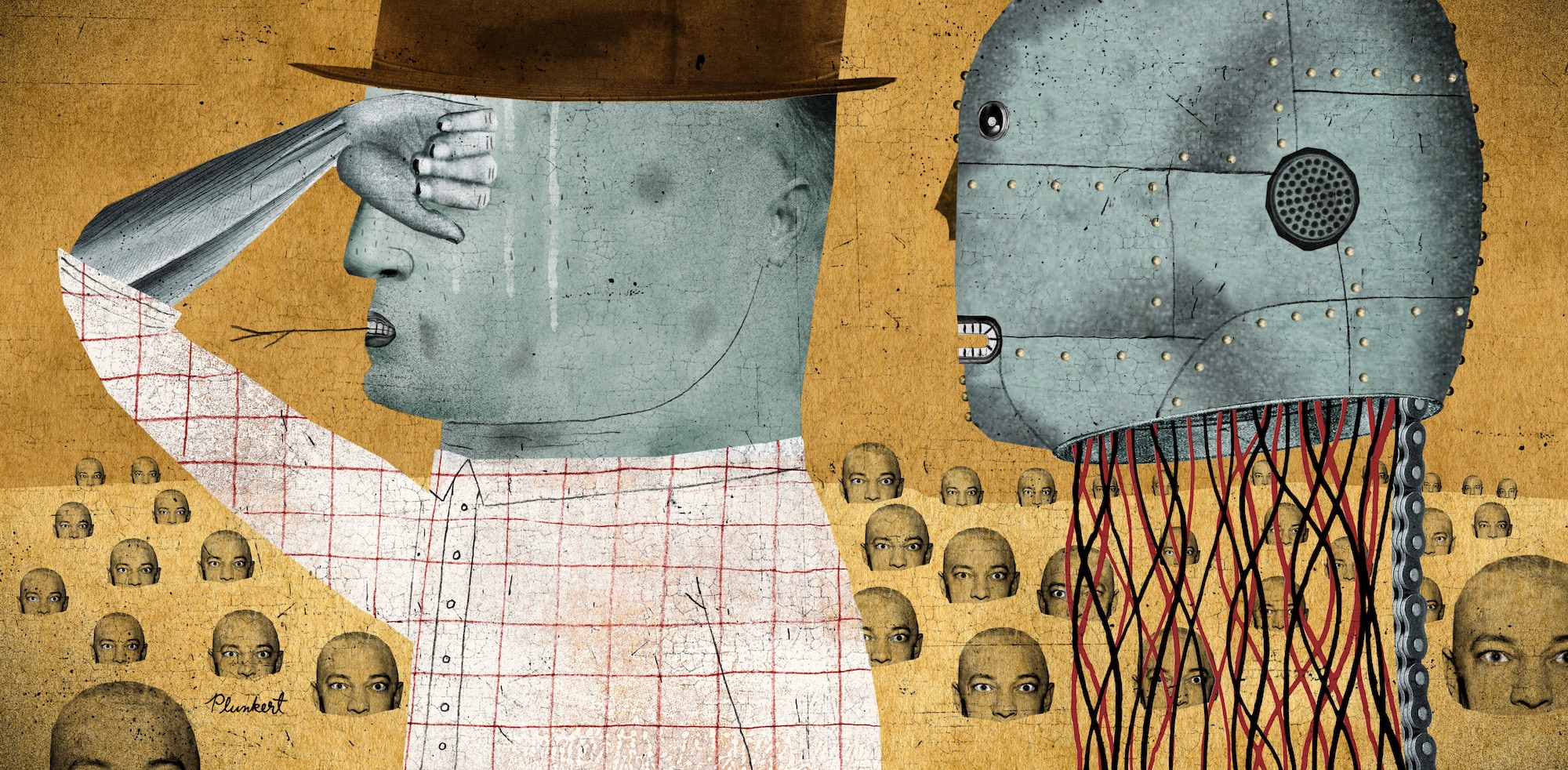

Illustrated by David Plunkert | Edited by L. D. Lewis

Copyedited by Chelle Parker

May 2020

Douglas dug deep into the sack of thumbs, sowing handfuls as he walked the muddy field. He kicked a few strays into the furrows, nudging dirt over wrinkles and cuticles and hair, and when his bag ran dry, Albert handed him another.

“Gonna be a good crop this year,” Douglas said as he opened the medically-sealed bag. “CryDon wants another bushel of nerves, and last I saw the price of torsos was up. Rest’ll be sold whole — unless another damned static storm comes through.”

Albert said nothing. Douglas had disabled the robot’s speaking capability, as it kept suggesting ways in which it could help, which, it turned out, wasn’t helpful.

“Hello! How may I be of assistance?” Albert had asked upon assembly. “My internals tell me plowing season has arrived. Or I am equally skilled at risk assessment. As my host company says, ‘I live to help live!’”

Albert followed Douglas out the barn door — silently now, as its vocal wires hung in a knot below the speaker box — but, even in silence, its presence was overbearing.

Albert sped ahead and propped open doors whenever Douglas approached a greenhouse. In response, Douglas would turn and walk the other way, annoyed at the assumption — which tended to be correct. Albert would project holograms of incoming storm clouds, agriculture reports, and coupons for HomoGrow, which Douglas dismissed with a quick swat. Even when it doesn’t talk, it’s noisy…. Eventually, he led the machine back to the barn and nailed it back in the box, needing a day in the field to determine what to do.

He’d been the first in NewBraska to invest in a fully-functioning AgraAutomaton and, while he had no prejudice against the metalmen, he wasn’t convinced he wanted the machine to talk back. Plus, he’d heard the neighbors gossip: “Corporate money.” “False farmer.” “Doesn’t need it, the showoff….” And while they were right about the last point — he didn’t need it, he could keep up with the demands of farm life just fine, even if his legs did ache most nights — he knew they were wrong about the rest. He’d scrimped and saved, but appearance was everything. Ultimately, Douglas programmed Albert for the basics: pull the cart, carry seed, and listen. Albert always listened, and Douglas always talked.

The lasers of Albert’s eyes tracked the fullness of each bag of thumb-plugs, ready to hand over the next sack as the pair approached the greenhouses. “Pause movement, please, Al,” said Douglas as he activated his mag-belt and stepped through the electrical field surrounding the buildings. “I shouldn’t be long.”

The greenhouses sat on hardened wheels, ready to be moved remotely once the tufted tops of the newest crop of clones began poking headfirst through the dirt. Inside, Douglas fiddled with the hydration system — several of the IV tubes had become tangled in the aerator overnight — as a thousand sets of eyes watched in silence, their mouths still trapped beneath the soil.

“Resume. Our journey continues,” said Douglas as he stepped outside. Together, they walked behind the row of glass domes, stopping occasionally to inspect the tension in the razor wire fence.

They crested the hill that marked the end of the property. Douglas checked this point daily, ever since finding a set of clones twisted into the wire. A fluke, he thought. Mature clones this far down the line had been known to produce motor skills unprompted. But then it happened twice more, and he logged the violations online.

Unsurprisingly, his neighbors saw nothing. And while clones stopped appearing in his fence, it wasn’t uncommon for a rock to plummet through a greenhouse panel or bacterial discharge to appear on his doorstep.

Even the patrolwoman was unsympathetic. “It’s not like you don’t have the credit,” she said. “You’re runnin’ a sophisticated operation here, but you’re living like a caveman. Just invest in some security.”

So Douglas invested in Albert.

“Sit with me, Al. If you’d like, of course.” Douglas perched on the bluff’s ridge. Albert sank down, eyeing the empty sack in Douglas’ hand. “Hey, we’re done for the day. Enjoy the view. Can you enjoy the view? I guess I’ve never asked….”

From the other side of the fence, drones carried baskets of algae and nutrients to animals. An automatic irrigator swept over crops and artificial clouds blocked radiation from the sky. Douglas waved at the drone operator where he worked in a nearby tower, but the pilot kept his hands on the controls.

“So, tell me, Albert, what’s the difference between us and them? Their crops? My clones? They know my soil’s no good anymore. And it’s not like I’ve got enough room for putting creatures to pasture. You use what you’ve got. That’s what I’ve been taught.” Douglas paused, waving again at the man in the tower. The operator just frowned.

“And Dad said — he said — that times were changing. Traditional farming, it just can’t survive. What am I supposed to do? Let the farm die? Sell it?” The wind tore the empty sack of thumb-plugs from Douglas’ hand, but he made no move to catch it. “Not that I’ve got any family to hand it down to anyway.”

To his right, he heard only the metallic skrit as Albert tinkered with his controls. Probably running an update, Douglas thought, watching the bag blow into the adjacent field. He picked up a stone and threw it as a drone buzzed over the fence line, but its sensors sent it weaving away back towards the tower.

“It’s just…. A guy gets lonely out here, you know?” Douglas threw another rock into the air. “And the worst part is that I’ve got more bodies per square foot than anywhere else in the damn state. But the silence just gets bigger and bigger, no matter how many greenhouses I add. And sure, the body parts save lives, but does anyone know it’s me who grows them? I tell you what, I’ve never gotten a Thank You note from a little girl or boy who just had their heart replaced by Cavanaugh, Inc. Nope. Not once. Bet they think they got a real part from a real person. Never want to peek behind the curtain. But we’re not monsters, huh? We’re people. Well, me anyway.”

Albert continued to tinker, fingers itching along iron skin.

“I’m sorry to unload on you, Albert. I know I’ve been doing it often.”

The farmer and the robot sat on the hill as the vapor-clouds shrank into nothing and the drones returned to their docks.

“I’m here to help,” said Albert, and Douglas looked up, shocked, at the jumble of reconnected wires in the throat of the machine. The wind rustled the sagebrush and peppered them with bits of dirt.

“I know, Albert,” Douglas sighed, resting a hand against the neck of his companion. “I know.”