Like Stars Daring to Shine

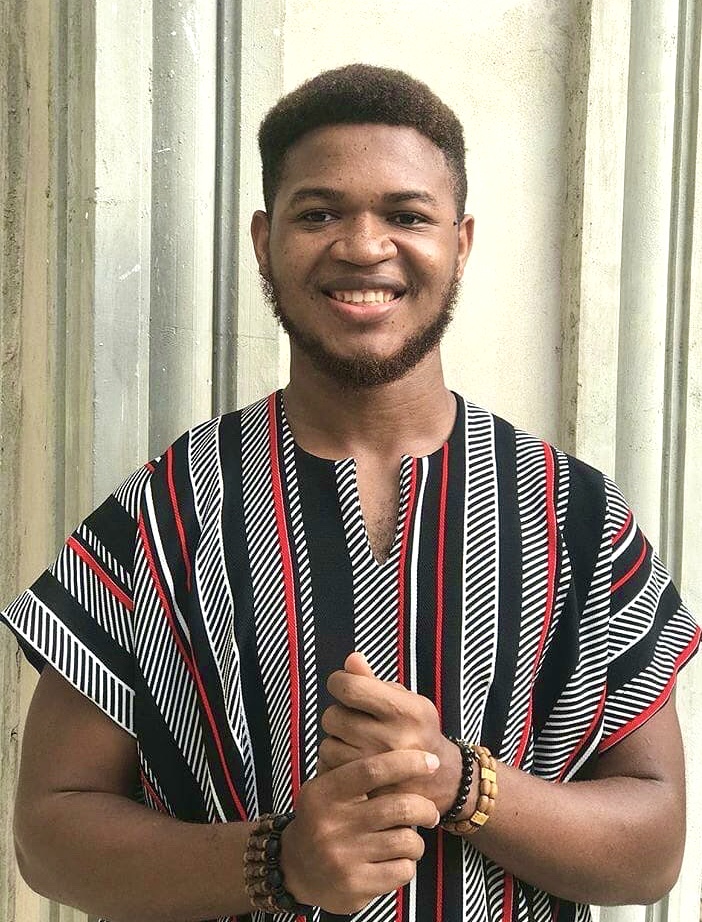

by Somto Ihezue

Edited by L. M. Davis

Copyedited by Chelle Parker

July 2022

2623 words — Reading time: around 13 minutes

When the boy opens his housing unit’s steel door and the incandescent lights pour into his face, he does not blink away. “Little suns” — this is what everyone calls them. The massive disks hover in the atmosphere, spilling streams of radiant light to the ground. The boy stares into the trees, mere meters from the door, and the forest encaving the unit stares back. A breeze finds him, whistling through the trees and into his dungarees. Threadbare with a Batman logo printed on them, the overalls belonged to his mother when she was a child.

Peeling his hand off the latch, the boy steals into the bright night. He hurries into the bushes, steering clear of the stone-paved forest pathways, each step sending emerald grasshoppers chirping off the shrubs. In the forest, its canopy a roof of green, darkness collects in patches, but the lights find a way — they always do. Through holes in the dense cover of leaves, they pierce the dark, creating lines of shimmering mist. The trees above crash gently into each other, and the rains that had collected in them fall to the boy’s skin in beaded drops. The musk of damp wood, bold and consuming, fills his nostrils as he weaves through the low-hanging palm fronds.

Before the light zones, the world had many green places — rainforests, savannas, mangroves — stretching as far as the eye could see. Not anymore. The Anambra Light Zone, with its damp places and its bird calls, is the only home the boy has ever known. He knows which months the leaves yellow and fall; he knows the poison mushrooms, their caps a vivid toxic scream. He knows the stones that birth the streams; he knows the places the Niger River breaks.

The boy stops when he sees the electric fence of the Multi-Science Research Facility, the words RESTRICTED AREA plastered across it in red. Made up of rows of cuboid structures, the facility stands at the west end of the light zone, with carpets of green algae crawling over it. When they were bored of tree counting, he and the other zone children would sometimes hide in the udala trees and guess at what might have once been the colour of the buildings.

“Vermilion.” Kiki, who had a crack zipping across the lens of her glasses, always said the strangest things.

“That’s not a colour,” some chunky kid laughed.

“Raymond, you thought peanut butter was mashed meat,” she replied to the chunky kid without looking over at him. “Maybe sit this one out.” She adjusted her glasses, fiddling with the duct tape that was doing a terrible job at holding the hinges in place.

“That was a long time ago!” Raymond looked around to the others, begging to be believed.

“Not long enough, apparently.”

Nobody liked going river jumping or antelope watching with Kiki, and this was why. She didn’t want them around either, but holed up in the zone together, they were stuck with each other.

Thirteen years ago, in the eternal winter of 2125, the boy and Kiki had been born here. They went to the same zonal school, climbed the same trees, and chased the same squirrels.

But Kiki was not one for words, and when she was, the other children ran back to their units in tears. So when she leaned forward in history class and whispered into the boy’s ear, “Meet me by the facility, under the udala trees,” he thought she’d mistaken him for someone else. But she hadn’t. “11 p.m. Don’t be late.”

“No talking,” Mr. Adesua, the geography teacher who also doubled as the history teacher, warned the class, his narrowed eyes jailed behind thick oval spectacles. “Now, where were we?”

He turned to the holographic board. “…Yes, on the 14th of May, 2060, Mount Nyiragongo erupted in the Congo Basin, an eruption that spanned ten months. With increased steaming, rumbling aftershocks, and smoke emissions occurring for the next decade, it was the longest, most intense volcanic disaster after the 1815 eruption of…?”

Mr. Adesua looked around at his students — some doodling on their holo-pads, others fiddling with their glow pens, and only a precious few making an effort to feign attentiveness. “Anyone?”

“The 1815 eruption of Tambora in Indonesia.”

“Thank you, Kiki,” the teacher sighed, resuming his lecture. “With an endless fount of ash saturating the atmosphere and obscuring the sun, Africa, our continent, truly became The Dark Continent.” A trail of dread crept into Mr. Adesua’s voice. That same dread found its way onto the faces of his now-attentive students.

“Sulfuric acid aerosols increased the reflection of solar radiation across the globe. Rivers and lakes in Greenland froze over; in Russia, buildings, cities, and millions of people were entombed in ice. And for the first time since the Ice Age, equatorial regions experienced winter….”

The boy’s attention drifted as he wondered what Kiki wanted with him. This was the first time she’d said more than a sentence to him. And though he made up his mind not to, he would later find himself hunching by the facility’s fence, breaking curfew.

Shifting his weight from one foot to the other, arms crossed tightly over his chest, the boy tries to stay hidden. An industrial-grade air filter thrums next to him, sending soft vibrations up his legs. With the incandescent “little suns” blazing bright, it is just a matter of time before the tight security team spots him.

Equipped with a self-regulating heat-yielding capability, the little suns warm frozen landscapes while simultaneously taking over the real sun’s photosynthetic role. This made the Anambra Light Zone home to some of the last surviving biological species in Nigeria, as well as the rest of the planet — which is the reason it’s heavily guarded by high-voltage walls against poachers and raiders from outside.

“Boy.” The boy looks up to find Kiki hanging from a branch. “You’re late.” She lets go, and when her feet meet the ground, they do not make a sound.

“This doesn’t feel right,” the boy says, his breath quickening. “Let’s—”

“There’s no security on this side. I checked.” She takes his hand. “Come.”

They slink onto the Facility grounds through a rip in the wired fence and head towards one of its many buildings. At the entrance, Kiki slips out a key card. She slides it across the door-lock, and it buzzes open, revealing an empty hallway.

“My dads work here,” she explains, catching the questioning look on the boy’s face. “Research biologists.”

Half-tiptoeing, half-running, hand in hand, they hurry down the hall. The walls on each side are large glass panes, and behind them are laboratories full of things the boy has seen only in books — microscopes, Petri dishes, titration filters, jars with brownish stuff floating in them — and, in some of the rooms, things not in the boy’s books.

Kiki whirls around. “What are you doing?” His hand has slipped from hers.

The boy leaves her to peer through one of the glass panes. “Is that a—?”

“Yes. A prototype. Let’s go.” She pulls on the strap of his overalls, but he does not budge.

“I want to see it.”

“You’re seeing it now.”

“Up close.” He goes to the door, and Kiki knows she’s not winning this one.

“I am so going to regret this.” She swipes the key card across the lock.

Inside, a little sun fills the room. Far from what the boy imagined, it is not flat but cylindrical, like a bass drum, and insanely massive. And there is nothing ethereal about it. Wires, plugs, and circuits jot out from within it, like twigs on a dying tree. He runs his finger along its dusty metal exterior.

Kiki stiffens where she stands. “We need to go.”

With its two surfaces — one plated with blue solar cells, the other made of columns of fluorescent tubes — the little sun is in practice a solar-powered streetlight, only larger and more complex.

“How does it work?”

“I. Don’t. Know.” Kiki punctuates every word, exasperation working into her voice.

But of course she knows. Unlike the boy, she paid attention in Introductory Tech class. To fight the climate crisis, world governments invented the “little suns.” The disks, a hundred times more powerful than the average solar panel, absorb light energy from the sun, converting it to beams too concentrated for the sulfuric aerosols in the atmosphere to reflect. And so, dusk till dawn, the little suns shine, sentries on guard.

“Woah.” The boy looks up. A map is etched into the ceiling. “Is that a world map?”

“More like a map of what’s left. Come on. Let’s go.”

“What are those? The red spots?”

“Light zones.”

“So few?” He slants his head. “Why couldn’t they just shield the whole world?” He gestures to the prototype.

“Do you ever listen in class?”

The boy shrugs.

“With limited time and resources, the advanced multi-purpose billion-dollar design of the technology was not accessible enough to enclose entire countries,” Kiki starts like she’s reading out of an encyclopedia. The boy blinks at her. “A compromise was reached, and the suns were suspended over arable lands, wildlife reserves, and forests.”

“Monaco did it.” The boy smirks, crossing his arms. He knows something she doesn’t.

“Monaco was a very small, very wealthy nation,” Kiki sighs. “They could afford to shield their entire landmass.”

The boy looks back up. The area above the US and its five zones is a sheer patch of white. “Mr. Adesua said Canada was a frozen graveyard long before a little sun got mounted.”

“The aftermath of the eruption was hardest on polar countries. Most had to migrate their citizens towards the equator, to Kenya, Indonesia, Colombia, and here. Sure, it’s cold here, but it’s tolerable.”

“Do you think the people on the outside are okay?”

“Seeing as they’re always trying to get in here, I take it they’re not.”

“We should just let them in.”

“We— We can’t.”

“Why?”

“There’s barely enough room and resources as it is. We can’t risk an overpopulation crisis. Our parents are only here because the work they do is important, nothing more.”

“My mum doesn’t work here in the facility like your parents. She’s down in agriculture.”

“And without her, we’d all starve, including those on the outside relying on us for monthly supplies.” Kiki takes his hand again. “I want to show you something.”

They head to the end of the hall and down a spiraling metal staircase. The stairs empty into a mass of interlocking pipes and dripping tanks that comprise the central grid of the drainage system. A chemical stench hangs in the air.

Kiki lifts a sewage lid like she’s done it a hundred times before, and the lights spill past her, into the dark below. “Get in.”

“No.” The boy backs away. “I’m not jumping into some random sewer.” His astonishment at seeing the prototype is long gone at this point. “I knew I should never have come.”

“So why did you?”

“I don’t know. I thought maybe you— I don’t know.” He coughs once, scratching the side of his neck.

“Oh god, you thought I wanted to kiss you?” Kiki’s expression cannot decide between disgust and shock.

“Ye— No— That’s not what I meant.”

“Just get in.”

Too embarrassed to protest further, the boy climbs down the greasy wet ladder. Following him, Kiki closes the lid, and the sewer goes pitch black. In the forest, under the cover of the canopy, the boy has experienced shades of darkness, but nothing like this. This is encompassing, ripping him of his sense of space, of being. He cannot tell where his body ends and where the darkness begins.

“Kiki, where are you?!”

“Relax, I’m right here.” She shines a headlamp in his face.

“I want to go back.”

“Not yet.” Handing him a lamp from the row of others hanging on the sewer wall, she trudges ahead, dispatching puddles of water with every step. The boy follows. Walking with a knowing sway, Kiki does not pause when the tunnel splits in three, and — unlike the boy — does not shriek when a rat scurries over her toes.

“How many times have you been down here?”

“Hm,” Kiki mutters, and nothing else.

The air starts to smell of river rocks as the pipes, mucky water, and defined walls give way to a larger, rough, cave-like exterior. Kiki stops.

“Are we there?”

“Turn it off,” she says, switching her lamp off. “They don’t like the light.”

“Who?” The boy hesitantly does as she says. “Who doesn’t like the—”

Then he sees it: a speck of light afloat in the dark. Another follows, twirling and glinting, up and up. A third comes, then a fourth, then a thousand.

“Fire— Fireflies.” The word leaves his lips as a whisper, his breath catching in his throat.

“Have you ever seen anything like it?” The swirling lights glint off the lenses of Kiki’s glasses, casting her entire face in a scintillating glow.

In the cave’s immensity, swelling with the euphonic hum of lacy wings, swarms of fireflies dance, a rain of stars. No, the boy has seen nothing like it.

“But….” He finds his voice. “My mum said…. She said they all disappeared when she was little. She said the lights blinded them. She said—”

“I know, I know. The lights made their mating glow invisible and, unable to evade predators or reproduce, they went extinct. I know.” Kiki lets her impatience show. “But look, they’re right here!”

“How did you find them?”

“I didn’t. My dads have been coming down here for months, studying them, how they’ve survived this long.”

“I guess the warmth from the little suns helped.” The boy inhales the fresh warm air.

“About that….”

“What?”

“Don’t freak out, but we’re not in the zone anymore.”

“Where— Where are we?”

“Where do you think?” Kiki scoffs.

It takes a minute, but it comes to the boy. His eyes widening, he spins around, frantic.

“No, no, this is a good thing.” She reaches for his shoulders. “We’re outside the zone, but it’s not freezing down here. Don’t you see what that means?”

“We can’t— We can’t possibly be that far away?”

“We’ve been walking for hours.” She beeps her timepiece in his face. “It’s 6 a.m.” The boy gasps. “I’m usually faster on my own, but thanks to your side quests, we are definitely getting caught. Point is, the earth is healing,” Kiki says, her voice charged with something the boy cannot describe. “My dads say soon we might not need the little suns anymore.”

“Really? How soon?”

“They’re not sure.” She pauses for a minute. “But can you imagine? Seeing the oceans, a sunset, the moon!” Her hands tighten around his shoulders, and she shakes him. “Boy!”

“Zaram.”

Kiki raises a brow.

“My name is Zaram.” The boy stares down at his fingers.

“And all this while I thought it was ‘Boy.’” She lets out a mocking chuckle. “I know.”

Zaram looks up at the fireflies. “Kiki, why— Why did you pick me?”

She does not look at him, but not in the same way that she doesn’t look at the other zone children, like Raymond. “Well, out of everyone here… I hate you the least.” A shy humming silence builds in the space between them. “What would you like to see, Zaram, when the earth is normal again?”

“I— I—” He has never thought about it. This — the light zone, the little suns — is his normal.

“It’s alright,” Kiki smiles. “You don’t have to think about it now.”

Zaram smiles back. And they stay, watching all the little things daring to shine.