Sheer in the Sun, They Pass

by Hester J. Rook

Illustrated by Paul Kellam | Edited by Aigner Loren Wilson

Copyedited by Chelle Parker

January 2022

2594 words — Reading time: around 12 minutes

I do not remember dying except for the feeling of waking, and waking, and waking.

I wake again every dusk. The sky blooms with red or fades in a wash of pink. The moon gapes from a slit of sky, as though I am reborn only in places I can see the night. Glowing among a puncture of stars, I exist again from nothingness. My own body feels strange and solid, and the rooms about me sharpen into focus before they fade, translucent as onion peel, and I can see the way into death.

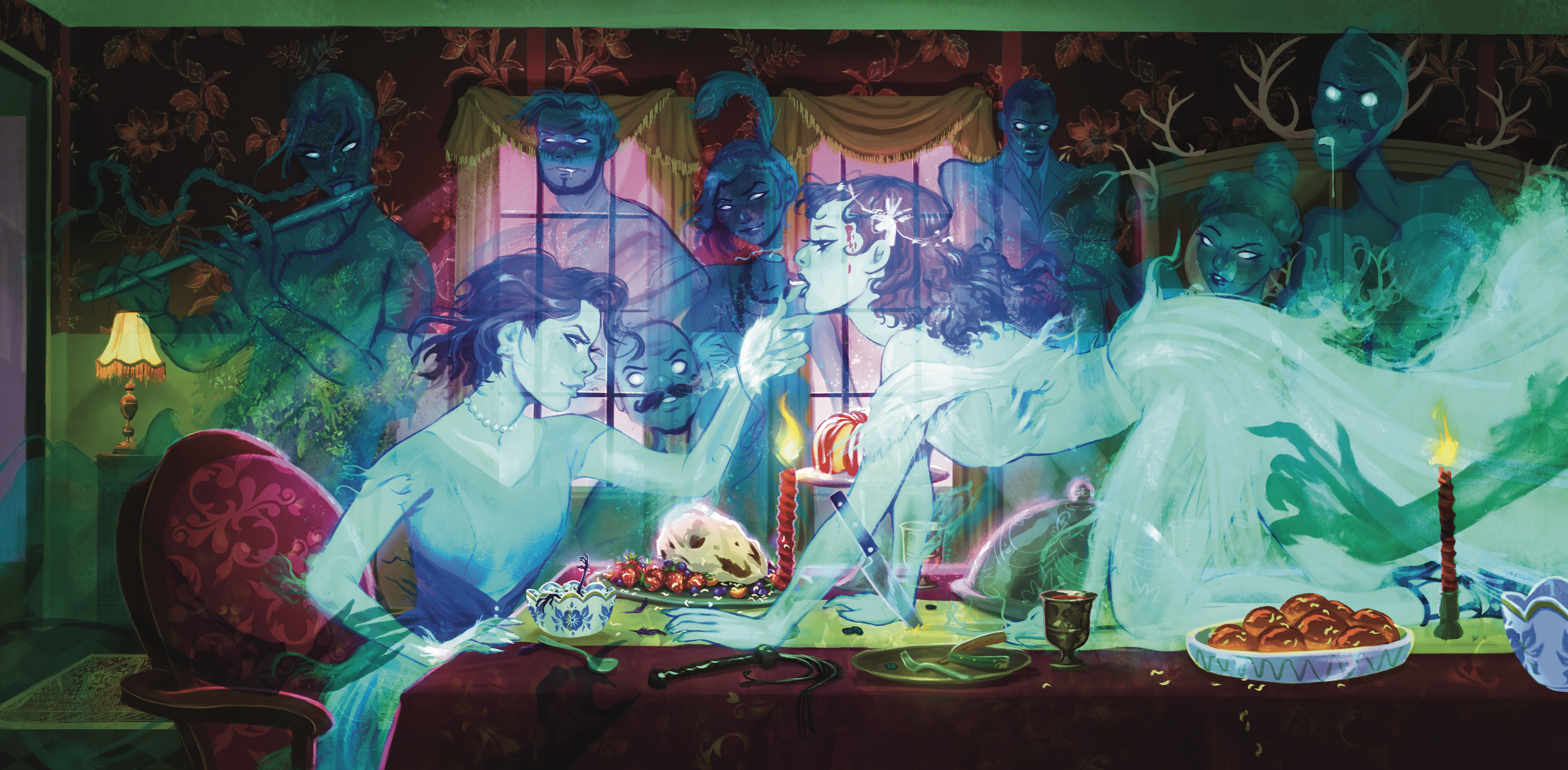

Each night, I step through the door. Where else would I go? I walk along corridors filled with corpses until a hall unfolds, and in that hall is a table laden with goodness, and in that hall is her.

“Amber, love, there you are.” The gunshot at her temple is a ruby glisten, a spillage of pomegranate seeds. She twines her fingers in mine and, superimposed over the arch of her left zygomatic bone, the children of the house whisper between themselves. “Come, look what has arrived for tonight.”

She leads me to the table and plucks a fresh strawberry from a plate, brushes a maggot from it, places it in the empty air where my tongue should be.

“That room is haunted,” says the tall child, translucent in the house, hair dark as smokebush, occupying the space my lover would stand if she were real.

“I missed you.” Rosa smiles at me, and her beautiful skin shifts around the glisten of wound.

“I’m not scared,” a smaller child insists, looking up and through me, mouth in a hard little line.

The table is stacked full of tea tree honey; slices of apple, crisp and cold; crumbs of coffee; plates of pastries studded with sugar. I eat and taste all the worldly seasons with a tongue that does not exist in any world.

The last child hides behind the others, so all I see is the flutter of breath against oversized pyjama pants. “We should go back to bed.” The third child this time, nose scrunched.

“No, Alana, we should go in. I dare you.”

I place lomandra seeds on Rosa’s tongue, pluck glisten-purple dianella berries and place them against her eyes, and we tousle with each other. There is bruise-purple wine and razor-slashed bread. From the house, a muffled giggle, like an escaped butterfly, reaches me just as, in death, Rosa tugs me close to her and whispers a kiss against the stump of my neck. Her lips are very cold, like the frosted grass I can no longer feel.

“Come,” she says. “In the other rooms, there are figs today! Figs! And a new musician has joined us.” I follow her as the children cross the threshold through her sternum and gaze, flutter-lashed, at my half-realised shape.

The figs are sticky-sweet, and Rosa feeds me cheeses baked in honey, quince compote slathered on fresh bread, grapes plump and ripe off the vine. She chews out the sour pits of cherries, places dollops of jam and thickened cream upon the empty air where she imagines my mouth used to be.

Her fingers are as cold and ghastly as mine, but here, in this place, she is the only thing that warms me. Time passes like it does in life, and so for us it is sparse and peculiar. Sometimes we dance, pick up our feet and twirl to tempos that make us shudder and gasp. Sometimes we sit and talk, and I cradle Rosa’s face with my long fingers and trace the shape of her, hold her close. The new musician is a silvery form, drenched through, water weeping from the ends of their braid. They look strange and unsure, in the usual way of the newly dead, until they pick up their flute and pull haunting notes out through its barrel.

Dawn glows through the sky in the lands of the dead and the living simultaneously, their twin lights diffusing both worlds I inhabit. As the fickle sun reaches each one of us, I see, for a moment, their hauntings — there, a spirit materialises sharp and hard into the concrete cube of a prison cell; there, our drowned flautist crests a wave, hair flung behind them in a barrage of salt; Rosa, alone on the hill, her skull sheared open; a smiling child, enveloped by a crib; a bone-thin man, collapsed into a hospital ward; myself, knees hard on the floorboards, wholly in the house once more.

I look up to the shout of the soft-eyed alive child before, once again, in the daylight, I cease to exist.

Time passes, in the way of things.

The house remains tied to me, the image of it superimposed across my eyes no matter how long I traverse the halls of death. I might see a thousand new dead places and befriend a thousand new ghosts, but I only ever circle those eight small rooms.

Their living inhabitants move across my vision as they walk through their own soft nights. They grow older and they change, and from this I know that years have passed. The eldest child leaves and returns sometimes with his own children, small things who are impossible and young. They look at me, and I lose my appetite, no matter how high my plate is filled with ripe peaches and pale cheeses. I hear them squall in the depths of the night even when I hold Rosa against my sternum.

She feels trapped too, she tells me. She haunts the hill but really, she says, the hill haunts her. She knows intimately the small creatures that crawl across the grasses, the winds that swoop the leaves. The stars are mocking her, she says. Sometimes she swears they move about on purpose. But surely that’s impossible? None of us know enough about the sky to answer.

For myself, the walls about me feel as though they are shrinking.

The longer we are here, the stranger we grow. The eldest ghosts are barely recognisable as having once been people. They grow grey and luminous as the insides of oyster shells, pick their bodies apart, and combine screaming with others to create new and strange things. Rosa and I become ravenous and revelrous. We ground ourselves in each other, gorging on the feast to fill up the empty ache that replenishes each dawn when we are reborn for those few seconds in those places to which we are pinned.

Our feasts grow stranger, discordant. Rosa feeds me buttons from a discarded funerary coat; the eyes of blackbirds; a carton of rusted razors, one sharp swallow at a time. I press shards of wallaby skull between her lips and marvel at the way the skin around her bloodied skull shifts as she chews.

We steal away together as midnight gathers us in her arms, and when I hold Rosa, we are wilder, rougher. She drives her nails into my side, and for a sweet swallowing moment, as pain blooms through me, I see her hillside. The wind sweeps the eucalypts, and I gaze longingly at the round disk of the moon, and as Rosa snarls, I know she sees, for a mere moment, my house’s redgum wardrobe, the bedframe tucked into the corner of the spare room, the gumboots that are muddied and discarded by the door.

I plead for pain more often, after that.

We become in the habit of bite marks and pinches and nails dragged across skin, of holding each other so tight that we cannot struggle away from each other. Still, I am surprised when, one dead night, Rosa takes my hand and leads me to a quiet corner of the hall.

“Amber.” Her breath is hot against my shoulder, and I thrill at this phantom sensation. “Amber,” she whispers again, “I want you to hurt me.”

She has brought something, some detritus from the feast, and her eyes shine as hard as the stain of her bloodied face. “I found this,” and it is a riding crop, leather soft and unyielding as the ocean.

I cannot form my question without a mouth, but she understands me anyway.

“No, love. Have you not seen? It’s my turn. I want you to hurt me.”

And I do not quite understand what she means, but that night and every night after, I thrash her til her eyes are glassy with desire and pain, and if blood still thrummed in her, she would have blossomed with bruises. Some nights, when I beat her, she vanishes from me. She returns some time later, reappears in some part of our dead land, and she is glowing and roiling with contentment in a way I have not seen for years.

I no longer know time, only what is before me. I have tied her up against a post, wrists and ankles blooming knots. She is naked and smiling, and we have an audience, a soft, smug milling of bored ghosts. They are preoccupied; we all are. All our hauntings feel like prisons, and we watch half-distracted as they happen to us while we try to exist with each other in this place. My house looms ever larger in me, and sometimes I am not sure if the house is not all I have known, if my companions and our feasting are not merely kind hallucinations to make my imprisonment bearable.

But right now, my lover is bound before me, and there is a many-tailed flogger in the seat of my palm, and she is smiling at me. I see it for what it is: a challenge.

There is nothing I need think about but her. The shiver of her as she bucks against each lash. The soft sheen of sweat. The careful read of her response. Her noises — breath and moan and request and prohibition. I am dimly aware of the murmurs of the others — coarse jokes and admiring commentary and chatter — but all my attention is on Rosa, reading her, serving her.

My thumb is in her mouth and my fists are pulling her hair and my palms are rough against the parts of her that were once abundant with flesh. She is in front of me and she is in the house and she is on the hilltop, and if I still had my skull, I would bite down on her shoulder until it opened for my missing mouth. Instead, I touch her gently with the knotted tips of the flogger, a deceit of softness, until she begs.

Then, I gift her everything.

I deliver a final blow. The ghost of her skin opens like a split peach, and she vanishes.

This time, she does not return.

It is the sixth night without her, and I pace the halls. The ghosts press at me but I cannot eat, cannot converse or laugh or carouse, because Rosa has not returned and I do not know where she has gone. I do not know how to bring her back and it is my fault. She vanished under my care, she was beneath my hands, and then she was gone.

It is the thirteenth night without her, and I realise I know Rosa’s hill. It comes to me like snow settling on branches. Her hill is stained on her and I know it as intimately as I know her, its myriad plants and small animals, the shape of it jutting towards the sky — a shape familiar against the windows of my own godforsaken house. Did I know it when I was alive? My memories are as empty as my belly.

I still cannot bring myself to eat. The others try cajoling me at first, bringing me tempting platters of honeycomb and dark, bitter greens and gem-yellow lemons, potatoes roasted in fat and macadamias round as pearls, and then, with increasing desperation, plates of rusted screws and mud and engine oil. No morsel tempts me, and eventually, one by one, they stop trying.

I am not sure I hunger exactly any more, but I do fade, and some nights I swear I am far more anchored to my house than any place ghosts should inhabit. I become more liminal, feeling most solid in doorways, in dawn and dusk. I try to trick my captivity. Perhaps, if I am quick enough, if I race from the door to the gate just as dawn shatters the night, I can leave this place and run to Rosa’s hill and find her, find her, find her. Each morning, I try to flee, and each morning, I return solidly to death just as I reach the threshold.

I have lost count of the nights.

What am I but ghost and haunting and nothing and shade? Without her, I am without purpose. Spread thin across two worlds, I inhabit neither.

The people in the house murmur more frequently in the night when I drift past them, forever retracing step after step, trailing my hand against walls more familiar to me than my own self, even as the halls of death unfold their limitless rooms to me. Here, the bounds of my existence.

As I waste away in death, I grow more substantial in life. Paintings rattle in their frames if I step too heavily; a stray elbow knocks a glass from the table. I notice this and find it new and strange, but even as glass shatters under my feet, I cannot tempt the curiosity in me.

There are visitors in the house.

In death, I am seated on a chair near the flautist, as they swing their drowning hair in stomping rhythms. In life, I am seated on the guest bed, where a woman sleeps restlessly. The worlds flicker and merge.

The woman stirs at the weight of me — how peculiar it is, after all this time, to have a weight to me — and addresses me by her husband’s name. She is soft as moonlight as she lies there, and I realise I hurt in a way I have not felt since I was alive. I am empty and aching and yearning — most of all yearning — for my love and her punctured skull and her gentle, ragged-toothed smile.

The hitch of the woman’s breath is loud, louder than the frantic flute and stamping of feet. I turn to find her eyes on my severed stump of a neck, and I see her and see that she sees me, that the cotton weave of bedspread is real under my touch, that the stars glisten in opposition to the snatch of moonlight, and that all else is silent. The halls of death and my reveling companions are simply no longer there.

There is nothing but myself and the house and the trembling breath of this waking woman who has found a spook on her bed.

The fingertips of a stirring breeze brush the branches of the trees outside and I rise, not daring to hope, not daring to do anything but walk to the bedroom door and tread down the familiar hall, and for the first time since death, for the first time in all my memory, I step out across the threshold and into the night.

Into the world.