XY

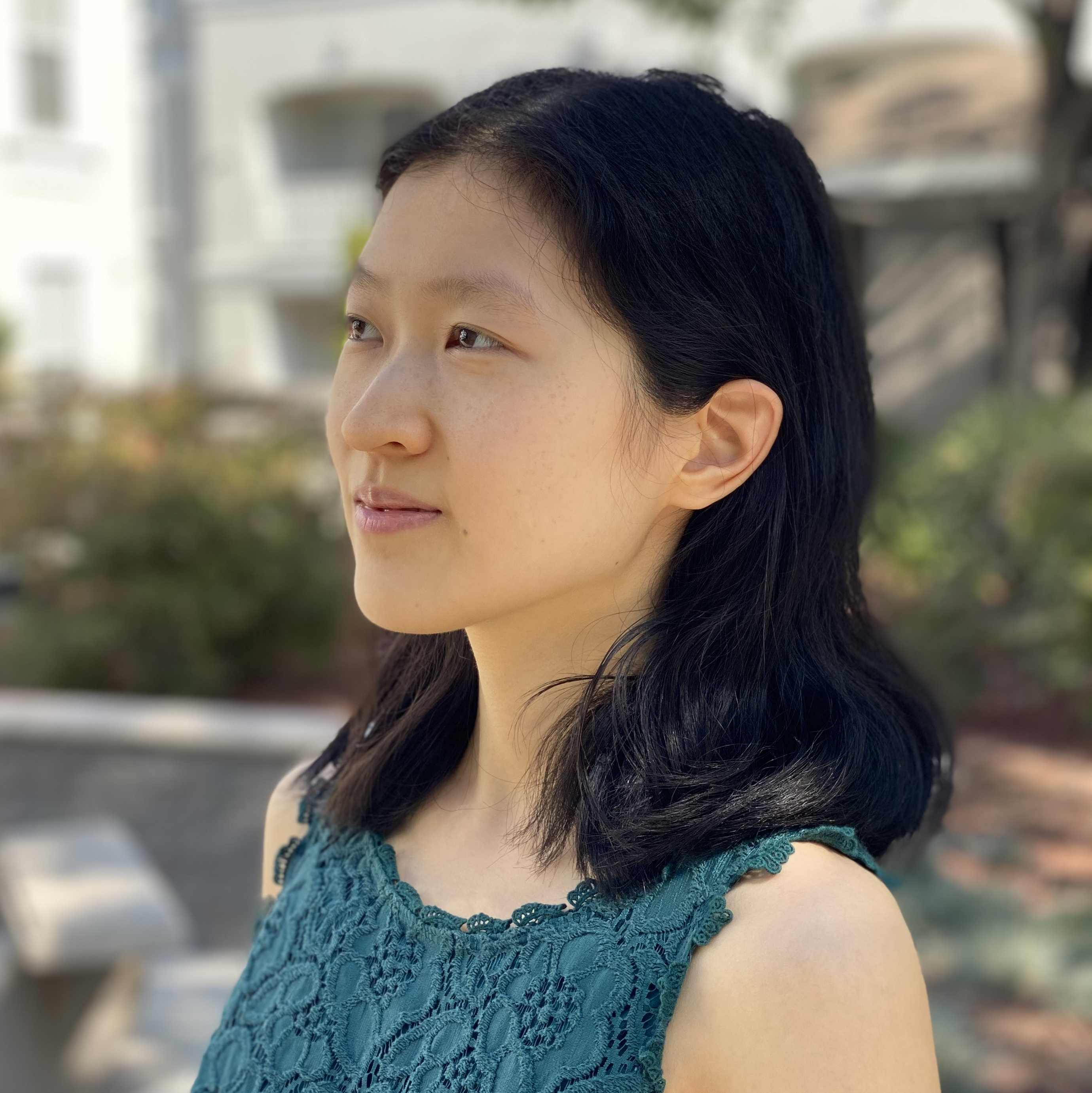

by Lucy Zhang

Edited by Hal Y. Zhang

Copyedited by Chelle Parker

May 2022

1966 words — Reading time: around 9 minutes

Content Note:

This story contains depictions of non-consensual medical experimentation and controlling family dynamics.

Before mom and dad had me, they had another child. She was called XY and was tall and pretty, with the type of long hair boys yanked on because they wanted an excuse to touch it. Mom and dad built her in their lab: plastered collagen scaffolded around bones of crushed ceramic and coral. XY emerged from the tank of formaldehyde as a fourteen-year-old — the age where you’re not fully emotionally stable and your moral compass starts to grey. Mom and dad chose this age because it made them feel alive, like seasoned and battle-worn parents.

I’ve never met XY. Mom tells me XY expired, but when I ask dad, he says they’ve “taken care” of her.

Mom is the doting parent — the one who will wake up an hour before me to prepare breakfast even if I wake up at 5 a.m. for a morning run, or if I’m flying home on a red-eye. Without fail, she’ll have a bowl of hot congee and a plate of steamed pork bao that had been proofed and wrapped the previous day. I ask her not to bother, since I’m old enough to know how to microwave oatmeal and boil eggs, but I suppose she’s afraid I’ll revert to my beans-and-rice diet if I’m left to my own devices. (“Accidentally trained you to be too frugal,” she says.)

Dad doesn’t dote, but that’s mainly because he doesn’t notice or remember anything: not when we’re low on garlic, when the laundry basket is full, or when it’s Sunday instead of Saturday. I think all of his energy has been reserved for a few laser-focused things, like whether I’m hanging out with a guy in the evening and that’s why I’m not having dinner with the family.

I never ask about XY. Mom and dad rarely mention her, so I assume it’s a topic they’re avoiding and will tell me in due time, although it’s not as though they’re trying to keep it a secret, with family photos of the three of them propped on the overmantel.

Kind of like when they inserted arrays of electrode threads into my brain, each array containing custom chips for “low power on board application and digitization.” It happened after I failed pre-algebra and no amount of tutoring or yelling would improve my grades.

At the time, dad said it was a standard operation, like getting the flu shot, and not to worry, because the neurosurgical robot knew how to avoid specific brain regions and vasculature with micron precision. He had me lie under the robot’s insertion head, under a pincer-like needle the length of a penny. I wasn’t allowed sedatives because my brain needed to be active so the machine could detect different regions of activity.

It took forty-five minutes for the needle to penetrate my meninges and brain tissue and insert the polymer threads. I don’t remember if it hurt. (“There’s no need to remember the painful things,” mom said.) Dad put a lot of effort into the insertion path planning, carefully marking a coordinate frame with landmarks on my skull, poking at just the right places in the thalamus and cerebral cortex until I felt nothing and silently listened to the needle motor buzzing above my head.

After the insertion and several trials for mom and dad to fine-tune the algorithms, I began to do well in school. And after several iterations of sampling and digitizing the amplified signals, I became good at talking to people too. This translated into finding a good job, earning a respectable salary, marrying someone I was compatible with — the surefire “input-output effort-yields-results trajectory,” as dad calls it.

My parents retire next month and want to move somewhere with lower property taxes before their grand plan to travel to the Galapagos. I don’t know when I’ll next see them, so I decide to visit. They call me filial, although this is all I’ve known: sending them paychecks once a month even though they don’t need them, scheduling Weee! deliveries of yams and bitter melons because they’ve decided to cut out rice from their diets, replacing their modem and router even though they insist the Wi-Fi is fast enough to stream videos. Old age has made them less picky. They’ve stopped building multi-electrode polymer probes and refining neural networks, and they sold their existing inventions to the first brain-machine interface company that asked.

When I enter the house, empty moving boxes clutter the foyer. I shimmy into the living room, where dad watches vloggers film their dumpster diving hauls and mom lies on a yoga mat, pulling one leg to her chest and then the other. I begin disassembling the lamps and cushioning them with sweaters to nestle in a box.

“Anything you still want in the basement?” I ask. They say no, which means I get to keep whatever I find interesting.

It’s a treasure trove down there: tungsten-rhenium wire packaged in oscillated coils, stereoscopic cameras, thin films of gold, dusty GPU machines used as shelves for scratch paper. I push open lids of crates, fishing through wires, trying to find a spare hard drive I can take back to free up space on my personal computer. I pry open another rectangular crate, this one long and narrow and deep, without slot handles so I have to maneuver my way around it to lift the heavy top rather than drag it toward me.

The lid is too heavy for me to lift. I slide it sideways until it crashes to the ground. It almost nabs my right toe. Inside the crate is a girl, hair positioned over her shoulders, arms crossed on her chest, skin a bit shiny like it’s not quite real.

I know she is XY because I’ve seen pictures of her: the prototypes mom and dad sketched, the weekly check-in entries documenting her behavior, the old vacation photos I’d seen of her and my parents flying a drone by the lakeside which they’d later take me to for my fourth birthday. She hasn’t changed at all, her skin preserved by some synthesized ingredient — maybe additives of rubber or plastic, although according to the observation records, her skin should mimic keratin. Her body has been frozen in time.

“Hi,” I tell her, thinking I look more like her extremely young mother than her younger sister.

XY’s eyes flutter open. “It’s been a long time.”

I nearly stumble on the fallen lid, thinking this is how I die — from uncovering a long-buried sepulcher harboring a vengeful spirit, the product of my ancestors’ wrongdoings rippling its consequences into my fate. Mom and dad shouldn’t have left XY in the basement. That’s a horror movie waiting to happen.

But I’m not surprised, because they tend to stow and forget, like when they locked the pantry shut after discovering a mouse in the container of fried sesame sticks, opting to starve it out rather than set up traps. We reopened the pantry several months later only to find stale shrimp crackers, expired Nature Valley bars, an open bag of sesame sticks, and no mice. Or the times they locked me in my room when I misbehaved and the chip needed a reset and retrain. My room was the control environment. Back then, mom and dad tinkered more than they slept, running analyses on stimulations to my brain. But they couldn’t monitor the signals 24/7 and wanted to avoid overexposure, so when they were busy, they’d keep me in my room with my school textbooks and printer paper. (“It’s not your problem,” dad had said. “Mom and dad will fix everything.”)

“I’m your younger sister,” I tell XY before she has the chance to ask me something I don’t want to answer.

“You don’t look like it,” she says, voice clear as though her vocal cords had never gone on a several-year hiatus.

“I was conceived,” I explain.

“Holy shit,” she says, eyes wide. “That means you’ve had menstrual cycles?”

I recall watching blood drip onto the tiny owls patterned on my underwear. Almost immediately after flushing the toilet, I received a text from mom: You can find the MaxiPads in my bathroom. She’d gotten a notification from the signal processing system: Apparently, the neurons go ballistic when your body goes through puberty, although I hadn’t felt terribly different beyond the annoyance of having to be careful about blood staining my clothing. Mom and dad spent the night clicking through the data captured, amplifying portions they found significant. They would need to update the software, they told me, which meant another hour or so under the needle and the robot whom I had begun to call “Mighty” since “robot” felt impersonal.

“Unfortunately,” I say. “Still do. Sucks to clean up. Can’t wait until this is over.”

XY tells me she never had a period. Mom and dad didn’t build her body with the functionality, since she was never meant to age. But she knows the theory behind it, because she knows the theory behind everything, since her brain updates to Wikipedia’s database every millisecond.

“Even while you were in here?” I point to the casket-like crate. “Also, Wikipedia isn’t very reliable.”

“Of course. Did you think I was dead? Dead people don’t come back to life. That’s the definition of being dead.”

XY stands up. I lend her my arm in case she needs help stabilizing, but she doesn’t. I should’ve expected as much, because her coordination and balance aren’t tied to shrinking telomeres and a declining muscular system.

I say, “Here, let me help,” but I’m the one holding her arm, as though I need to confirm she’s real. Her pulse beats against my hand. I can see her veins through her gossamer-like skin. My arm looks like a piece of plastic compared to hers.

After XY steps out of the crate, I pull over two foldable chairs. We sit, and I ask her what it was like in the dark all those years.

“It’s not like that,” she says. She explains how her brain still accesses the world even when her body is shelved away.

“But it must’ve been dark,” I insist, thinking about the blank walls of my childhood room, the boarded-up windows, the white light.

“I had a lot of time to myself, is all,” XY replies.

She tells me about the things she learned while sealed up: the proper way to care for a cast-iron skillet; how to tie bows so both sides are even; why the idea of a brain in a vat is invalid, because doubt requires context and a baseline of realism, and anyway, the search for meaning is hardly any more difficult if material reality were an illusion.

In turn, I tell her how mom programmed out my obsession for peanut butter noodles, and how dad trained my reward system to value solving matrices over doodling dragons in the margins of my papers.

XY asks me if I still hate peanut butter noodles today, and I say, “Of course. Just the thought makes me nauseous.”

She stares at me.

I stare back until my eyes water, then I blink and look away.

“Well, just because that particular flavor has been obsoleted from your system doesn’t mean you can’t try with sesame butter,” she says and shrugs. “Peanuts, sesame — both are fragrant enough.”

We talk for at least an hour before I ask XY if she wants to see mom and dad. XY shakes her head. She stands and steps back into the crate, lowering her body slowly with her arms gripping the sides. I realize how physically strong she is despite not moving for years.

She pauses, extends a hand to me, a little USB port poking from her palm, and asks if I’d like to join.